Whicker's wicked world

Michael Deakin

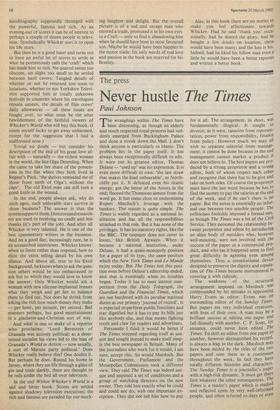

At the beginning of Alan Whicker's autobiography* is a photograph of the author at the outset of his career — a reporter, then working for what was the most shabby and hopeless newsagency, Ex- tel. It shows a press conference given by the Third Man, Kim Philby. Whicker is in the front row with the photographers, a Wood- bine glued to his lower lip, in a rumpled suit with a badge on the lapel and shorthand pad on his knee. The image is sharp and clear: a shabby down-trodden hack worse still, an agency man on linage. On the back cover in full colour lounges the Whicker of today — the world's richest, most glamorous and well-travelled reporter. He is evenly tanned, a Gucci shirt unbut- toned to the waist, a Cartier knick-knack around the neck, doubtless a watch with a double-barrelled maker's name on his wrist. And above all, he is contentedly relaxing at home in a tax haven.

This fascinating book chronicles this apotheosis — telling the extraordinary tale of how a hack became a millionaire socialite, how a linage man finally made it between hard covers. And on the way it reveals not only perhaps more of its subject than he intended, but illuminates the very stuff of our popular television since its debut 25-odd years ago. For the saga, Whicker has marshalled a cast of thousands — the perverse, the snobbish, the powerful, the famous and the billionaires. Some members of this cast flash by with only a couple of lines pulled out of old scripts, but some, especially the super-rich, are lovingly gloated over. Paul Getty gets a whole chapter with loving details of his exact wealth — how much he earned per minute, how he could pay the income tax of the whole nation.

Whicker and his journalism belong in the Fifties when anybody lucky enough to get in front of a camera could become an ins- tant star, such was the novelty of the whole thing. The rich knew nothing of the all- seeing eye of the camera or of the damage and the laughter it could provoke among the poor and ordinary people whom they had never met and who actually had televi- sion sets. The rich, busy on the slopes at Gstaad or the beaches of the Costa Smeralda, were flattered and vain when the mighty BBC came to call, even in the per- son of an inquisitive man from Extel. It was like the old story of the Astors' butler dur- ing one of the recurring family scandals — `Sir, the men from the press are at the door', he is reported to have said, 'with a gentleman from The Times.' In the Fifties *Within Whicker's World Alan Whicker (Elm Tree Books £8.95)

the butler would have said 'from the BBC'. The gentleman would have been Whicker -- and he wasn't. Nowadays the rich, like everybody else, know that times have changed and trust no one, especially from television.

But then it was different, and Whicker had the luck to be there just when all these changes were about to happen. He acknowledges the fact gracefully — a quali- ty which is in short supply in the rest of this book. And Whicker's luck held in another way. When he entered the BBC by way of the renowned Tonight team under the redoubtable popularist Donald Baverstock he was taken in hand by some of the best producers and brightest young directors ever to have worked in television. Together they made programmes people still remember, and then moved on to make feature films and plays — until only Whicker remained, beached in a style of entertainment which no longer interests the young and the talented. Only the public re- mained undeniably faithful to the gradually sinking ship, like the television's equivalent of the ageing and out-of-joint readers of the Sunday Express. Only now, like a sort of television Flying Dutchman, Whicker has to travel further and further to find rich people foolish enough to hold themselves up to his ridicule. And as the `jet set' these days embraces practically everybody, it becomes a problem to find places so distant that no ordinary tourist can return home and question the reality of Whicker's world.

New young directors took the place of the old team, who to a man refused an- nually to return to the styles and triumphs of their youth. Whicker disliked the newcomers and often insulted or ignored them. Three of the programme controllers of the current ITV companies have directed Whicker's World over the last few years none of them is given credit in this book.

One famous member of the Whicker's World team, however, is. The very first chapter o f the book is devoted to the research- er and later producer who for ten years and upwards of 80 films shot all over the world researched the famous programmes. This man unearthed the subjects and the interviewees; then, when Whicker arrived, sometimes weeks after filming had started, he booked the 'star' into a suite in a five- star hotel far away from the crew, and wrote a list of questions on pink card for Whicker to mull over before the famous face-to-face. His reward is a scandalous story under an assumed and comic name a personal attack which would have been out of place in private, let alone in an

autobiography supposedly thronged with the powerful, famous and rich. As an evening-out of scores it can be of interest to perhaps a couple of dozen people in televi- sion. Symbolically Whicker uses it to open his life story.

But then he is a good hater and turns out to have an awful lot of scores to settle in what he portentously calls the 'craft' which has made him so rich. No quarrel seems too obscure, no slight too small to be settled between hard covers. Tangled details of whether or not he returned too soon to locations, whether or not Yorkshire Televi- sion supported him at totally unknown festivals in countries where his travelogues remain unseen, the details of film crews' daily allowances — all these issues are

fought over, to what must be the utter bewilderment of the faithful viewers of Whicker's World who will buy this book. (I count myself lucky to get away unharmed,

except for the suggestion that I had a malformed nose.) Trivial no doubt -- but consider his description of the end of his great love af- fair with — naturally — the richest woman in the world, the late Olga Deterding. When she came to take her share of the possess- ions in the flat where they both lived in Regent's Park, 'the shelves reminded me of those front teeth of Olga's without the caps'. The old Extel man can still turn a good knife in the wound.

In the end, people always ask, why do such egos, such unlovable stars survive in show business? The answer is that the systemsupports them. Directorsandresearch- ers are used to receiving no credit and less thanks (it's part of the job). And after all Whicker is very talented. He is one of the best commentary writers in the business. And on a good day, increasingly rare, he is an unmatched interviewer. Whicker knows when to listen rather than respond, how to elicit the extra telling detail by his own silence. And above all, true to his Extel background, he knows when to ask the ques- tion others would be too embarrassed to ask but to which they would love to know the answer. Only Whicker would ask a woman with new silicone-implanted breasts

what they weigh and get her to balance

them to find out. Nor does he shrink from asking the rich how much money they make — per hour, per minute, per second. Bad manners perhaps, but good entertainment in a gladiator-and-Christian sort of way.

And what is one to make of a reporter who proclaims: 'Lord Bernstein of Granada was actively political; as a deter-

mined socialist his views led to the bias of Granada's World in Action — now usually,

a sort of Marxist party political.' Does Whicker really believe this? One doubts it. But perhaps he does. Round his home in

Jersey, where they see life through a glass of gin and tonic darkly, there are thought to be reds under the bed all over television.

In the end Within Whicker's World is a sad and bitter book. Scores are settled

against shadowy television executives; the rich and famous are paraded for our mock- ing laughter and delight. But the overall pictute is of a sad and savage man who entered a trade, promoted it in his own eyes to a Craft — only to find it abandoning him when he should have been its most favoured son. Maybe he would have been happier in the motor trade: his only words of real love and passion in the book are reserved for his Bentley.

Alas, in this book there are no stories to make you feel affectionate towards Whicker. Had he said 'thank you' occa- sionally, had he shared the glory, had he bought a few drinks on location, there would have been many; and the loss is his. Indeed, had he liked his fellow man even a little he would have been a better reporter and written a better book.

Previous page

Previous page