The end of an era

Arthur Marshall

Which would be your choice of year if some magic wand or Wellsian time contraption could waft a historian back- wards through the ages to provide you with a fully documented and eye-witness account of that year's events, illustrated with happy colour snaps of the principal figures (`They've caught that quizzical look of yours, Attila')? Apart from the emotional excitement of seeing and hearing and reverently touching the hem of You Know Whom, there is much to be said for an earlyish AD year (the few modern school children who still struggle with the dreaded Latin language will rejoice tO hear that bet- ween AD 8 and 9 and 19, Ovid, Horace, Livy and Virgil all kicked the bucket).

Or something around AD 61 might be quite jolly too, with Boadicea showing tremendous forin against the Romans, St Paul on dry land for once and in Italy, Nero hunting about for his resin and that box of Swan Vestas, and Christians being persecuted right, left and centre. Nearer our day, AD 1685 has things to recommend it death of Charles II, Monmouth's rebellion and execution, the Battle of Sedgemoor (the Somerset site affords a splendid panoramic view from a high speed train to Exeter on days when the driver isn't on strike), and Judge Jeffreys popping on that wig and practising outstandingly nasty facial expres- sions in the looking glass.

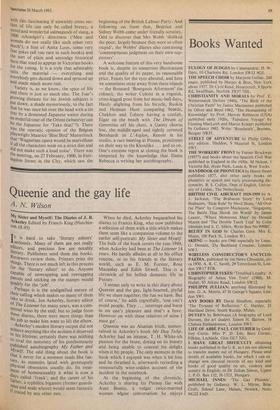

The year chosen, and to our great profit and advantage, by Rebecca West is the one that -began our fairly disastrous century, and if you question that adjective, ponder on the multimillions that it has already managed needlessly to slaughter. In that year she was aged eight (a charming photograph shows her being fed with black- berries on a picnic) and was still Cicily Fair- field — the assumption of her present name, that of the iron-willed lady in Ibsen's Rosmersholm, came later — and looked out on the world from a solid, comfortable, upper-middle-class background based on Richmond (the Surrey one), with its pleas- ing Queen Anne and Georgian houses and its associations with Swift and George Eliot, not to speak of its royal neighbours at White Lodge.

And if ever a year was jammed with thought-provoking happenings, most of them especially fascinating to a child, it was 1900. Much was afoot and there was an ex- cellent varied spread of events. After a great deal of stomach rumbling, Vesuvius finally decided to erupt, Mafeking was relieved, and the sun chose to eclipse itself totally. There was anti-war rioting in, of all im- probable towns, Scarborough and bubonic plague in Glasgow. The first Zeppelin flew, bombless we assume, and violent storms blew down part of Stonehenge, giving a faint touch of interest to what must surely be England's most boring ancient monu- ment, especially now that visitors are not allowed within 50 yards of it.

It was a fine year too for armed malcontents to take pot shots at notabilities. They scored bull's eyes on the German ambassador in Peking and King Humbert of Italy. Somebody had a go at our Prince of Wales (not, one would have thought, at that time a difficult target to hit), the failed assassin, a Spanish juvenile called Sipido, being released from prison when he was 21, 'with his political views probably unchanged, and with time to improve his marksmanship.' The Shah of Persia had a near squeak and they also failed, tell tell!, to bring down the German Emperor, and just think of all the bother that would have saved. The US President McKinley had to wait until 1901 for his lethal come-uppence. And far away in China, the Boxers caught the general spirit of unrest and, fatally for themselves, rose.

Naturally, not all of the stirring happen- ings here under review slot themselves neat- ly into 1900 and there are straddlings, in particular the shameful Dreyfus . affair which began in 1894 and ended, if it can ever be said to have ended, in 1906 and out of which almost everybody except Emile `J'accuse' Zola, Pope Leo X111 and Dreyfus himself (a pity he was so dull and colourless) came badly, the French officers of high rank who appeared as witnesses against him being likened to 'the super" nasties of The Duchess of Malfi.' Straddl- ing too was the Boer War which meandered sadly on until 1902 ('We no longer have the power of wholesale international in- terference') and in describing which, Dame Rebecca does a hatchet job on Lord Milner, Britain's South African High Commis- sioner, a man held in high and almost mystical regard by authority and who was `elected to the Chancellorship of Oxford University when dying of sleepy sickness at the age of 71.'

1900 saw the deaths of both Oscar Wilde and his persecutor, the Marquess of Queensberry, and we learn much of interest concerning 'the frenetic story of excep- tional misery in the Queensberry familY'• One of them, out shooting, blew himself to bits. Another managed to fall off the Mat- terhorn, while his sister, Lady Florence Dix- ie, 'was subject through the decades to inex- plicable adventures, such as being kidnap- ped in the heart of London'. Wilde's enemy, the ninth and 'enthusiastic atheist' Marquess, warmed up for better things by a public protest in the Globe Theatre at a character in Tennyson's inoffensive The Promise of May. Promptly ejected into Shaftesbury Avenue, he protested to more purpose later, though Max Beerbohm, visiting Wilde in his last years in France, found him buoyant and bobbish and with what Shaw called 'his unconquerable gaiety of soul', a noun that has recently caught 111) with him.

Our authoress rightly makes much of two important American imports of around that date — the novelist Henry James and the painter John Singer Sargent (`Both, strangely enough, looked like tnglish butlers ... They had large faces which never reacted to their emotions, but were flattened by the thought that if anything went wrong it would be awful'). It was Sargent who saved portraiture from the in- fluence of the French artist, Blanche Can engaging party who looked like a sheep), and although allowing that Henry James was 'a great, great genius', he is taken to task for a ,failing not unknown among American voluntary expatriates — appall- ing snobbery. When Lord and Lady Rosebery had put him up for the week-end, `his bread and butter letters could have been arranged for the organ as a substitute for the Magnificat' (which, for those not lately in cliurch, begins 'My soul cloth magnify the Lord').

In addition to these lavish and cornucopia-like dispensings of colourful personalities and unusual events, readers may by now have noted a bonus. The style which Dame Rebecca has evolved to cope

with this fascinating if unwieldy cross sec- tion of life can only be called breezy, a weird and wonderful salmagundi of slang, a 1900 schoolgirl's directness (Wen and women do not really like each other very much'), a hint of Anita Loos, some very fine jokes (all too rare in such books) and the sort of plain and unstodgy historical facts that used to appear in Victorian books for the young. It is a style that admirably suits the material — everything and everybody gets dusted down and spruced up and made much more real. Variety is, as we know, the spice of life and there is just so much else. The Tsar's growing distaste for his Jewish subjects is Put down, a shade mysteriously, to the fact that he was once hit over the head with a tin tray by a demented Japanese waiter during an eventful tour of the Orient (whatever can be the Japanese for 'Take that! '?). There was, the operatic opinion of the Belgian PlaYwright Maurice 'Blue Bird' Maeterlinck that 'Wagnerian opera would be marvellous Ica the characters went on a strict diet and did not make such a loud noise'. There was the meeting, on 27 February, 1900, in Farr- 1ngdon Street in the City, which saw the beginning of the British Labour Party. And following on from that, Beatrice and Sidney Webb come under friendly scrutiny. Odd to discover that Mrs Webb 'disliked the poor, largely because they were so often stupid', the Webbs' diaries also containing `contemptuous judgment on their own sup- porters'.

A welcome feature of this very handsome book is, despite its numerous illustrations and the quality of its paper, its reasonable price. Feasts for the eyes abound, and here we sometimes stray away from these islands —

the. Bonnard 'Bourgeois Afternoon' (in colour), the writer Colette in a roguish, cross-legged pose from her music-hall days, Hardy alighting from his bicycle, Ruskin and Holman Hunt comparing beards, Chekhov and Tolstoy having a confab, Elgar on the beach with The Dream of Gerontius off his chest, a Gaiety chorus line, the middle-aged and tightly corseted Bernhardt in L'Aiglon, Renoir in his studio, a race meeting at Poona, prostitutes on their way to the Klondike ... and so on. One's extreme regret at closing the book is tempered by the knowledge that Dame Rebecca is writing her autobiography.

Previous page

Previous page