Fashioning a career

Isabel Colegate

SKETCHES FROM A LIFE by Anne Scott-James Michael Joseph, £14.99, pp. 198 Be succinct, to the point, and entertain- ing. Such is Anne Scott-James' advice to the would-be newspaper columnist, and she has obeyed her own maxim in her brief volume of recollections. It follows her very successful Gardening Letters to My Daughter and uses the same formula; anything she doesn't want to write about can be dis- missed as liable to bore Clare. Not that the result is amateurish; she is clearly nothing if not professional, and can be scathing about those who are less so.

Anne Scott-James is 80 this year. She was a career-girl at a time when most women were not. Having loved school and hated Oxford, which in 1931 she found restrictive, anti-feminine, and conversation- ally limited, she abandoned a promising academic career and set out to be a jour- nalist. Such a thing as a youth cult being unimaginable in those days, she was required to spend three years learning her trade as a sub-editor before moving into Vogue's editorial department and learning the sprightly prose of the fashion maga- zines of the time (`pencil-slim', 'vibrant with colour', 'spiced with white'). Then came exhilarating years working on Picture Post, which she did throughout the war, Marriage to Macdonald Hastings, who was a Picture Post war correspondent, and two Children, to one of whom this book is addressed, the other being the present edi- tor of the Daily Telegraph; after the war she was editor of Harper's Bazaar, and then a Columnist on the Express and the Mail. Later on came a much happier second marriage, to Osbert Lancaster, and the burgeoning of a career as a garden expert, which has produced nine books and a seat on the Council of the Royal Horticultural Society.

Fashion photography has changed enor- mously since the black-and-white Thirties, and fashion drawing has disappeared, to this author's regret. She thinks the differ- ences between magazines then and now are

mainly changes for the worse, largely to be accounted for by the immense expansion of the public relations industry. She writes entertainingly about the dazzling glitter and vigour of New York in 1935 — Vogue gave her time off and she went out on the S.S. Bremen and back on the Queen Mary and cried all the way home. She is funny and affectionate about the friends with whom she worked, like the incurable romantic Lesley Blanch and the incurable cockney Bert Hardy who was one of Picture Post's most brilliant photographers. She is astringent about Rosamond Lehmann, whom she admired but found slightly comic in her personification as the femme fatale of the Berkshire village in which both lived for some time during the war, and about Nancy Mitford, whom she interviewed.

I grasped the nettle. 'Is my behaviour U?' She thought for a long time, for she had no wish to hurt me, only to tease, a favourite Mitford word. 'You have U legs,' she said kindly.

Jaunts with John Betjeman and Osbert Lancaster were happy times, as were travels in Greece with the latter. The author writes touchingly about the last

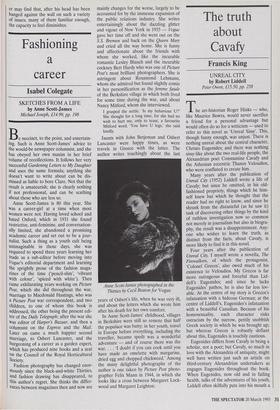

Anne Scott-James photographed in the Thirties by Cecil Beaton for Vogue

years of Osbert's life, when he was very ill, and about the letters which she wrote him after his death for her own comfort.

In Anne Scott-James' childhood, villages in Berkshire were still so remote that half the populace was batty; in her youth, travel in Europe before everything, including the traveller, became spoilt was a wonderful adventure — and of course there was the war. . . . 'I doubt if you can cook until you have made an omelette with margarine, dried egg and chopped chickweed.' Among the many delightful photographs of the author is one taken by Picture Post photo- grapher Felix Mann in 1944, in which she looks like a cross between Margaret Lock- wood and Margaret Leighton.

Previous page

Previous page