Exhibitions

Georges Roualt: the Early Years 1903-1920 (Royal Academy, till 6 June)

Taking a dark view

Giles Auty

Rouault is an artist who has lingered at the edge of my consciousness since I was a schoolboy. Until the present I have not been obliged to consider my precise response to his art in any detail. I suspect I may have shirked this experience deliber- ately.

One good reason for having done so is that I feel myself to be at the furthest remove possible temperamentally from men who see themselves as clowns, let alone those who paint themselves as tragic ones. This personal shortcoming has inter- fered seriously with my ability to like or even to be interested in the art of Cecil Collins, say, who was admired greatly by my late and esteemed colleague Peter Fuller, or in certain recent paintings by Philip Sutton. It is also an aversion which extends with particular force to fancy dress parties. I sense my attitude may be unrea- sonable yet seek to explain it nevertheless by reference to the second of the two cata- logue essays which introduce this new Royal Academy exhibition. As Fabrice Hergott remarks: `Rouault's preference for solitude made him indifferent to the world around him ... Rouault made no special effort to be understood by his contempo- raries (although he wished that they would understand him)'.

The present exhibition at the Sackler Galleries of the Royal Academy comprises some 94 works and was shown previously in Paris at the Pompidou Centre, where it attracted favourable attention even though the main galleries there are unsympathetic, in their scale, to smallish works. Rouault's works are on paper mostly and were exe- cuted with a consistently heavy-handed emphasis in combinations of ink, gouache, watercolour and other media. Many have darkened with age. Certainly the present exhibition is among the more sombre I have ever seen, whatever the medium, and is hardly calculated to lift the spirits either by subject matter or treatment.

When I discussed my reaction to the show with an artist friend, he said simply, `You never did like to see self-pity elevated to an art form'. However, I think this is an over-simplification of what I feel. Certainly, Rouault's devout Catholicism far from dis- poses me against him, but is this truly the underlying impetus of his work? Is his furi- ous concentration on the outcasts of soci- ety — prostitutes, criminals, the circus people of his day — simply a railing against an unjust society or, in reality, against an unjust God? Most of the human faces Rouault puts in front of us look morose, depraved or sinister. If these are portraits of souls, as has been claimed, then those put before us look beyond that redemption which is a central tenet of Christianity.

Are these caricatures of the human con- dition or simply expressions of the artist's own, unrelieved grief and rage? Is this lat- ter not, in fact, related to the nihilism which underpins the Expressionism of early 20th-century German artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner? In the exhibition cata- logue's first essay, Sarah Whitfield disputes such an idea strongly, claiming 'His [Rouault's] vision was one of affirmation, not Apocalypse'. On the other hand, this particular writer's use of classifications is often confusing. The first two sentences of her essay read: `Rouault was a strong, even an extreme, radical. It is hard to think of another prominent French painter so opposed to the fundamental tenets of mod- ernism'. Since the essence of modernism then as now was surely a condition of radi- calism, her choice of words seems unfortu- nate and muddling. In general one speaks of radicalism as opposing existing tradition rather than alternative modes of radical- ism.

The writer does not explain adequately either why she thinks Rouault's vision was affirmative rather than apocalyptic, based on the evidence of art from this particular period. Aside from figures from the circus and bordello, Rouault found a rich source of subject matter in courtroom procedures, as had Honord Daumier before him. Yet Daumier's art, though sometimes grim or satirical, still seems lighter and more humane than that of Rouault. Daumier combined monumentality with a certain litheness of line. While both artists employed quite sombre and limited palettes, Daumier took an interest in the fall of light, whereas many of Rouault's images, such as 'The Accused', 1908, and `Christ Mocked', c. 1912, seem devoid of illumination of any kind.

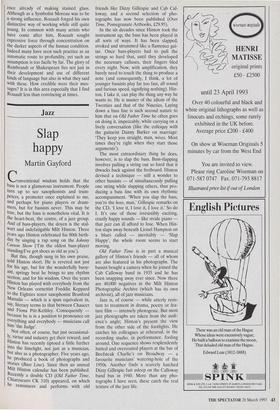

By the age of 20, when he enrolled in Gustave Moreau's class at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Rouault had five years' experi- The Baptism of Christ, 1911, by Georges Roualt ence already of making stained glass. Although as a Symbolist Moreau was to be a strong influence, Rouault forged his own distinctive way of working while still quite young. In common with many artists who have come after him, Rouault sought expressive force through concentration on the darker aspects of the human condition. Indeed many have seen such practice as an automatic route to profundity, yet such an assumption is too facile by far. The glory of Rembrandt or Shakespeare lies not just in their development and use of different kinds of language but also in what they said with these. How credible were their mes- sages? It is in this area especially that I find Rouault less than convincing at times.

Previous page

Previous page