THE PATHOS OF SPITALFIELDS

R APHAEL SAMUEL

SPITALFIELDS, when I first came to live here in 1962, seemed to be caught in a time Warp. The district had miraculously escaped the war-time bombing, perhaps because of its distance from the docks, and was as closely built over, if not inhabited, as it had been in the 19th century, when Christ Church, Spitalfields, was the most crowded parish in the metropolis. It was neglected by the local council. It was un- touched by the develop- er's hand. The streets were lined by bollards, as they had been in the days of horse-drawn traffic: even in the busiest of them parking meters were unknown. Lighting in the sides- treets was perfunctory, and, in the winter even- ings when mysterious fi- gures loomed up out of the shadows, it scarcely penetrated the gloom. The Georgian streets had been preserved by their poverty from im- provement.

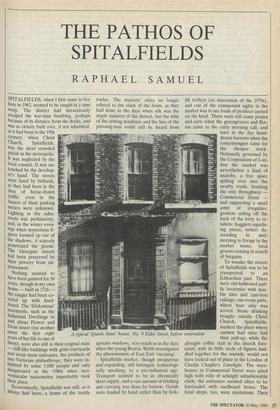

Economically, Spitalfields was still, as it always had been, a home of the textile trades. The weavers' attics no longer echoed to the clack of the loom, as they had done in the days when silk was the staple industry of the district, but the whir of the sewing machines and the hiss of the pressing-iron could still be heard from ueen Anne' house, No. 9 Elder Street, before A typical 'Q restoration upstairs windows, very much as in the days when the young Beatric Webb investigated the phenomenon of East End 'sweating'.

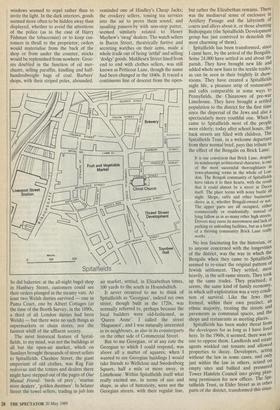

Spitalfields market, though prosperous and expanding, still belonged, technologi- cally speaking, to a pre-industrial age. Transport seemed to be in chronically short supply, and a vast amount of fetching and carrying was done by barrow. Goods were loaded by hand rather than by fork- To wander the streets of Spitalfields was to be transported to an Edwardian past. There were old-fashioned pub- lic lavatories with mar- ble tiles and cast-iron railings; one-room pubs, where beer only was served. Stone drinking troughs outside Christ Church, Spitalfields, marked the place where carmen had once had their pull-up, while the all-night coffee stall in the church fore- court, with its little circle of figures hud- dled together for the warmth, would not have looked out of place in the London of Charlie Chaplin's Limelight. The ware- houses in Commercial Street were piled high with rolls of achingly unfashionable cloth; the entrances seemed often to be barricaded with cardboard boxes. The local shops, too, were mysterious. Their windows seemed to repel rather than to invite the light. In the dark interiors, goods seemed more often to be hidden away than displayed, whether to avoid the attentions of the police (as in the case of Harry Fishman the tobacconist) or to keep cus- tomers in thrall to the proprietor; orders would materialise from the back of the shop or from under the counter, stocks would be replenished from nowhere. Groc- ers doubled in the function of oil mer- chants, selling paraffin, kindling and half- hundredweight bags of coal. Barbers' shops, with their striped poles, abounded.

So did bakeries: at the all-night bagel shop in Hanbury Street, customers could see their orders plunged in the steamy vats. At least two Welsh dairies survived — one in Puma Court, one by Albert Cottages (at the time of the Booth Survey, in the 1890s, a third of all London dairies had been Welsh) — but there were no such things as supermarkets or chain stores, nor the faintest whiff of the affluent society.

The most historical feature of Spital- fields, to my mind, was not the buildings at all but the open-air market, which on Sundays brought thousands of street sellers to Spitalfields. Cheshire Street, the giant emporium of old clothes, was Rag Fair redivivus and the totters and dealers there might have stepped out of the pages of Our Mutual Friend: `birds of prey', 'marine store dealers', `golden dustmen'. In Sclater Street the towel sellers, trading in job lots

reminded one of Hindley's Cheap Jacks; the crockery sellers, tossing tea services into the air to prove them sound, and assailing passers-by with non-stop patter, seemed similarly related to Henry Mayhew's 'swag' dealers. The watch sellers in Bacon Street, theatrically furtive and secreting watches on their arms, made a whole trade out of being 'artful' and selling `dodgy' goods. Middlesex Street lined from end to end with clothes sellers, was still known as Petticoat Lane, though the name had been changed in the 1840s. It traced a continuous line of descent from the open- air market, settled, in Elizabethan times, 100 yards to the south in Houndsditch.

It never occurred to me to think of Spitalfields as `Georgian', indeed my own street, though built in the 1720s, was normally referred to, perhaps because the local builders were old-fashioned, as `Queen Anne'. I called the street `Huguenot', and I was naturally interested in its neighbours, as also in its counterparts on the other side of Commercial Street.

But to me Georgian, or at any rate the Georgian to which I could respond, was above all a matter of squares; when I wanted to see Georgian buildings I would take friends to Wellclose and Swedenborg Square, half a mile or more away, in Limehouse. Within Spitalfields itself what really excited me, in terms of size and shape, as also of historicity, were not the Georgian streets, with their regular line, but rather the Elizabethan remains. There was the mediaeval sense of enclosure In Artillery Passage and the labyrinth of courts and alleys about it, or those abutting Bishopsgate (the Spitalfields Development group has just contrived to demolish the most charming of them).

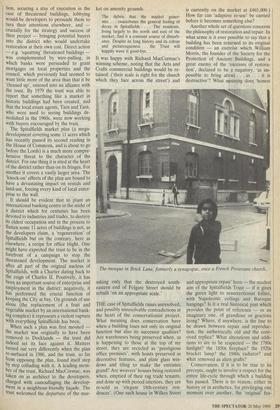

Spitalfields has been transformed, since I came here, by the arrival of the Bengalis. Some 24,000 have settled in and about the parish. They have brought new life and added whole new lines to the textile trades, as can be seen in their brightly lit show- rooms. They have created a Spitalfields night life, a pleasure strip of restaurants and cafes comparable in some ways to Pennyfields, the Chinatown of pre-war Limehouse. They have brought a settled population to the district for the first time since the dispersal of the Jews and also a spectacularly more youthful one. When I came to Spitalfields most of the people were elderly; today after school hours, the back streets are filled with children. The Spitalfields Trust, in a welcome departure from their normal brief, pays this tribute to the effect of the Bengalis on Brick Lane:

It is our conviction that Brick Lane, despite its nondescript architectural character, is one of the most successful thoroughfares in town-planning terms in the whole of Lon- don. The Bengali community of Spitalfields have taken it to their hearts, with the result that it could almost be a street in Dacca itself. The place teems with noisy bustle all night. Shops, cafes and other businesses thrive in it, whether Bengali-owned or not. The upper parts are all occupied, either commercially or residentially,' instead of lying fallow as in so many other high streets. Drivers may curse its narrowness and lack of parking or unloading facilities, but as a focus of a thriving community Brick Lane really works. . . .

No less fascinating for the historian, or to anyone concerned with the longevities of the district, was the way in which the Bengalis when they came to Spitalfields seemed to re-enact the original pattern of Jewish settlement. They settled, most heavily, in the self-same streets. They took up the same trades. They practised, it seems, the same kind of family economy, in which self-exploitation was a very condi- tion of survival. Like the Jews they formed, within their own precinct, an ethnic majority, treating the streets and pavements as communal spaces, and the shops and restaurants as meeting places. Spitalfields has been under threat from the developers for as long as I have lived here. In the 1960s, it seemed, there was no one to oppose them. Landlords and estate agents winkled out tenants and allowed properties to decay. Developers, acting without the law in some cases, and only just within the law in others, seized on empty sites and bullied and pressured Tower Hamlets Council into giving plan- ning permission for new offices. The Spi- talfields Trust, in Elder Street as in other parts of the district, transformed this situa- tion, securing a stay of execution in the case of threatened buildings, lobbying would-be developers to persuade them to turn their attentions elsewhere, and crucially for the strategy and success of their project — bringing potential buyers into the district who would undertake restoration at their own cost. Direct action — e.g. 'squatting' threatened buildings was complemented by wire-pulling, in which banks were persuaded to grant Mortgages on local properties and the council, which previously had seemed to want little more of the area than that it be `cleaned up', entered into an alliance with the trust. By 1979 the trust was able to report that something like a market in historic buildings had been created, and that the local estate agents, Tarn and Tarn, who were used to seeing buildings de- molished in the 1960s, were now working with buyers encouraged by the trust.

The Spitalfields market plan (a mega- development covering some 11 acres which has recently passed its second reading in the House of Commons, and is about to go before the Lords) is a much more compre- hensive threat to the character of the district. For one thing it is sited at the heart of the district rather than on its fringes. For another it covers a vastly larger area. The 'knock-on' effects of the plan are bound to have a devastating impact on rentals and land-use, forcing every kind of local enter- prise to the wall.

It should be evident that to plant an international banking centre in the midst of a district which for centuries has been devoted to industries and trades, to destroy its oldest occupation and in the process to flatten some 11 acres of buildings is not, as the developers claim, a 'regeneration' of Spitalfields but on the contrary, here as elsewhere, a recipe for office blight. One might have expected the trust to be in the forefront of a campaign to stop the threatened development. The market is after all part of the original nucleus of Spitalfields, with a Charter dating back to the reign of Charles II. Positively, it has been an important source of enterprise and employment in the district; negatively, it has performed the crucial function of keeping the City at bay. On grounds of use alone (the replacement of a fruit and vegetable market by an international bank- ing complex) it represents a violent rupture with everything Spitalfields has been.

When such a plan was first mooted the market was originally to have been removed to Docklands — the trust did indeed set its face against it. Matters turned out very differently when the plan re-surfaced in 1986, and the trust, so far from opposing the plan, found itself step by step colluding with it. A leading mem- ber of the trust, Richard MacCormac, was taken on as architect to the developers, charged with camouflaging the develop- ment in a neighbour-friendly façade. The trust welcomed the departure of the mar- ket on amenity grounds.

The debris that the market gener- ates . . . exacerbates the general feeling of decay in Spitalfields . . . . The residents, living largely to the north and east of the market, find it a constant source of disturb- ance. Despite its long history and its colour and picturesqueness . . . the Trust will happily wave it good-bye. . . .

It was happy with Richard MacCormac's winning scheme, noting that the Arts and Crafts commercial buildings would be re- tained: ('their scale is right for the church which they face across the street') and The mosque in Brick Lane, formerly a synagogue, once a French Protestant church.

asking only that the destroyed south- eastern end of Folgate Street should be rebuilt 'on an appropriate scale.

THE case of Spitalfields raises unresolved, and possibly unresolvable contradictions at the heart of the conservationist project. What meaning does conservation have when a building loses not only its original function but also its successor qualities? Are warehouses being preserved when, as is happening to those at the top of my street, they are recycled as 'prestigious office premises', with hoists preserved as decorative features, and plate glass win- dows and tiling to make the entrance grand? Are weavers' houses being restored when, emptied of their rag trade tenants, and done up with period interiors, they are re-sold as 'elegant 18th-century resi- dences'. (One such house in Wilkes Street is currently on the market at £465,000.) How far can 'adaptive re-use' be carried before it becomes something else?

Another whole set of questions concerns the philosophy of restoration and repair. In what sense is it ever possible to say that a building has been returned to its original condition — an exercise which William Morris, the founder of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and a great enemy of the 'excesses of restora- tion', declared to be a nugatory, 'as im- possible to bring about . . . as . . . it is destructive'? What meaning does 'honest and appropriate repair' have — the modest aim of the Spitalfields Trust — if it gives the green light to resurrectionist follies, with Napoleonic ceilings and Baroque hangings? Is it a real historical past which provides the point of reference — or an imaginary one, of grandiose or gracious living? Where, if anywhere, is the line to be drawn between repair and reproduc- tion, the authentically old and the cont- rived replica? What alterations and addi- tions to are to be respected — the 1780s fanlight? the 1850s fireplace? the 1920s bracket lamp? the 1940s radiator? and what removed as alien grafts?

Conservation, if it is to be true to its precepts, ought to involve a respect for the entire life-cycle through which a building has passed. There is no reason, either in history or in aesthetics, for privileging one moment over another, the 'original' fea- tures over the later additions. This is especially the case in a district like Spital- fields where so many of the buildings, both large and small, are hybrids, growing by additions over time. (The Truman, Han- bury and Buxton brewery in Brick Lane is a spectacular case in point.) A house is a palimpsest on which successive generations have left their mark, and all of them, in principle, are worth preserving. The mezu- zah (scrolls of the law) on the door-post of my basement kitchen — a sign of Jewish occupancy, perhaps around the turn of the century when Spitalfields was the heart of the ghetto — is no less a part of the history of this house than the 1795 coin of the London Corresponding Society found in the floor-boards; likewise the mid- Victorian range (as I imagine it to be) or the matchboarding in the basement have as much right to belong here as the rather warped Georgian shutters. Even my own small additions to the house — the Burgun- dy paintwork in my study, say, or the old quarry tiles on the kitchen floor — might be thought worth preserving, if only as a sample of 1980s Retro-chic.

In Spitalfields, houses have not been `done up' as they have been in other, newly gentrified parts of London. On the con- trary they have been painstakingly and often lovingly restored. The Spitalfields Trust, connoisseurs of the art of Georgian building, have presided over much of this work, controlling the building operations and using the services of specialist architects and craftsmen. Yet, for all the insistence on authenticity, there is an inescapable element of artifice. The houses are designed not as living and working environments, nor yet as family homes but first and foremost as period residences. The original features are retained, or restored, not as functional necessities but as decora- tive motifs, and there are symptomatic absences which suggests that the houses are being restored not to what they were, but to what their new owners would like them to have been. The candle sconces may be reinstated in the hallways, but not the privies in the yard. The Victorian kitchen range may be ripped out of the fireplace, to make it look more baronial, but nobody attempts to disconnect the mains water supply, or return to stand- pipes or water-carts in the street. The owners, moreover, notwithstanding the strict covenants of the Trust, seem unable to resist the temptation of improving on the original, reinstating features which ought to be there but are not (e.g. fan- lights). Entrances, stripped of internal porches and protuberances, are made more imposing, windows more dramatic, ceilings more ornate. Drawing rooms are richly furnished, dining-rooms glitter. The build- ings, in short, are socially and aesthetically upgraded, so that what begin as humble weavers' houses can end up as showcases of the restorer's arts. It is the pathos of conservation,, even where, as in Spitafields, it is carried out under expert guidance, that it produces the opposite of its intended effect. Returning buildings to their original condition (or attempting to do so) it robs them of the very quality for which they are prized --- oldness, that 'pleasing decay' as it was once termed by a rural conservationist, which has always constituted (at least to the outsider) the charm of the vernacular. Fetishising period, it freezes the building at a point where history has not yet happened to it. Removing every memory trace, it allows neither imaginative nor physical space for the barnacles which have accreted over time Even the attention to period detail,- however archaeologically correct, can be aesthetically counter- productive if it means that the period features, in order to be reinstated, have to be made anew. What merges in purist restoration, is a building that is innocent of history and shows no signs of wear and tear — the newly pointed brickwork no longer grimed with soot, the dados and doorways regularised, the cornices with their dentils all in place. However antique the effects, it is to all intents and purposes brand new. Office development, already well under way before the 'Big Bang', now threatens to engulf Spitalfields in a sea of neo- Georgian fakes. In a district where work and home are so intimately linked, its effects are necessarily traumatic. It is almost always accompanied by and indeed premised on, a revolution in occupancy, In which the existing set of tenants or users are displaced. It substitutes an alien for an indigenous working population, commu- ters (and computers) for native resident. It inflates property values in a district whose industries and trades have always de- pended on cheap work-rooms. In any competition for resources and space the Bengalis — who have done more than anyone else to revivify the district — are certain to lose out. They have no access to those funds which are fuelling the business recolonisation of the inner city. They do not have the ear of government ministers, or the support of the government majority — the allies whom the Spitalfields De- velopment Group has been able to call in play — nor are there conservationist bodies ready to come to their aid. They do not have influential friends in the local Council — a stronghold, under the Liber- als, of white residential respectability, deeply hostile to the Spitalfields trades. And sadly, in the present instance, they have seemed unaware of the destruction which is about to visit their streets.

Previous page

Previous page