Architecture

Housing the Airship (Architectural Association, till 27 May)

Cathedrals of the air

Gavin Stamp

When travelling through Bedford- shire, by train out of St Pancras, two strange, long, dark objects on the eastern horizon dominate the flat, dull landscape. These are the airship sheds at Cardington, which are as prodigious in size as they are now rare and special. Almost 800 feet long with an internal height of 156 feet — not far short of the height of Nelson's Column — and now listed as historic buildings, they Were intended to house Britain's contribu- tions to that short-lived experiment in air travel, the dirigible. While the airship has received appropri- ate attention, the structure evolved to shelter these lighter-than-air monsters has not, although it was equally remarkable technically. Such buildings, designed for both military and commercial use, were once ubiquitous and this spectacular ex- hibition, organised by Christopher Dean at the Architectural Association (36 Bedford Square, WC1), is devoted to exploring their history. To an extent, this show appeals on a nostalgic level, what with large intricate models and dramatic can- vases of moonlit Zeppelins. But it is primarily concerned with the technical solutions adopted to erect at high speed structures which were quite unprecedented in scale.

Like Barlow's train shed at St Pancras, the two Cardington sheds are supreme examples of engineering prowess in their time. But perhaps the airship shed is best compared with Early Victorian covered slips like those that survive in Chatham Dockyard: those monsters of iron technol- ogy which preceded the great railway sheds. For what is extraordinary about both the covered slip and the airship shed is that these innovative structures which pushed forward the frontiers of engineer- ing so quickly became redundant equally rapidly. The iron slip was a product of just two decades, between the evolution of large iron spans and the invention of iron ships which made protection from the weather unnecessary. Similarly, the history of the airship shed, enclosing much larger volumes, was not much longer.

Although the French, pioneers of flight, had designed structures to accommodate balloons in the late 18th century, the story really begins in 1899 when Count Zeppelin erected his first airship shed at Friedrichs- hafen on Lake Constance. By 1911, the Italians were erecting prefabricated airship sheds in Tripoli for military use in the war against the Turks. During the Great War, huge metal sheds were erected all over Europe for military purposes. Yet by the end of the 1930s it was all over. The future of the giant airship had finally been dashed by the spectacular burning of the Hinden- burg at New York in 1937. For Great Britain, the seductive dream of sedate, comfortable, roomy air travel had dis- solved seven years earlier when the R101 had set out for India from Cardington and crashed in flames at Beauvais.

But the airship sheds, like the airships they sheltered, owed nothing to the styles of the past. They were unadorned works of pure engineering, of careful structural analysis. In the beautifully produced ex- hibition catalogue, Martin Pawley argues that they were years ahead of their time, for

the requirement for strength and lightness posed by the rigid airships themselves forced the development of tensile wood, fabric and light alloy structures that were the forerun- ners of all the ground-born geodesic and space frame buildings that have been de- signed or erected since. . . . It is not too much to say that the engineering achieve- ment of the enormous airship sheds paved the way for the primacy of the structural engineer in the constellation of construction professionals that rules the built environ- ment today.

It is this conception of the importance of structure in modern architecture that accounts for the AA mounting this expen- sive pioneering exhibition, the first on the subject for 80 years, thereby again contri- buting to architectural studies in a stylish and imaginative manner that puts the timidity and philistinism of other profes- sional bodies to shame. (I note with interest that the opening of this show coincided with the launch of the Architectural Association Foundation to keep this admirable private institution afloat.) But it must not be thought that airship sheds were not architecture. Some were beautiful shapes, with rounded ends.

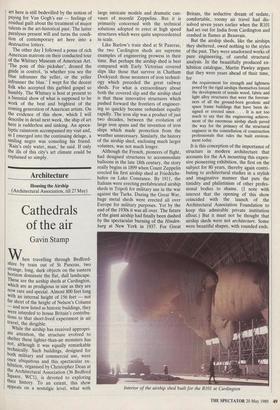

Interior of the airship shed built for the R101 at Cardington Most elegant of all were the sheds with pre-stressed concrete ribs of parabolic sec- tion erected by Freyssinet at Orly in 1923: a supreme fusion of necessity and inspira- tion designed by an engineer who relied on intuition as much as on calculation.

Sadly, the Orly sheds were destroyed in 1942. But we still have those at Carding- ton. Compared with Freyssinet's sheds, they might seem pedestrian: three-pin arches built up on steel A-frames and covered in corrugated iron. But they have a sublime beauty which is not a product of size alone. Even so, the sheer size is awe-inspiring. I once had the privilege of being on a catwalk at the apex of the 1917 shed — at a height which made the meteorological balloons below seem like little toys — when the huge sliding doors on rollers began slowly to close. The sunlight was gradually squeezed to a nar- row shaft cutting through the cavernous gloom: and then there was darkness. It was a moment of timeless sublimity to which the Hollywood of W. D. Griffith or Cecil B. de Mille might have aspired: the airship shed appearing like a great cathedral or stupendous basilica.

But the Cardington sheds are not just curious monuments, for the airship may yet revive. If these daring and daunting sheds really are the cathedrals of this century, they honour a faith which is still alive.

•

Previous page

Previous page