New York art

Paying for Van Gogh's ear

Giles Auty

The best treatment for jet lag', a smart (art) dealer counsels me, 'is a line of coke.' We are in New York, city of frenzied energy, at a party given by a famous firm of fine art auctioneers and I am feeling somewhat less than fresh off the plane. This is a city wherein to feel tired, let alone weak or poor, is really not acceptable. So, shunning any pathetic in- stincts for survival, I find myself still to be more or less upright in a night-club several hours later. When I leave, scores of bright young men and girls are dancing what little remains of a weekday night away. Do none have jobs to cope with later in the morn- ing?

When writing more usually from the other side of the Atlantic, the influence of New York on our perception of art in Britain often strikes me as of questionable benefit. When the United States decided to steamroller tired old European artistic culture in the late Fifties, New York supplied the intellectual energy and econo- mic clout necessary to make an excellent job of the operation. If the aim had been to make us Europeans perceive ourselves as artistically provincial, the stratagem was at least temporarily successul. For a long while the fashionable stars of art and of the museum hierarchy in Britain dwelt lovingly upon the greater opportunities and fuzzi- ness' of American culture. Hockney was merely one of our Wunderkinder who, but for a tightening of immigration laws, might have turned a trickle of art migrants into a stampede. Fame and fortune seemed to be there to be grabbed by those sufficiently fast on their feet. Yet might there not be some unseen or unacceptable reckoning to come one day from this contract with Mammon? Kindness and hospitality not- withstanding, my experience of New York this week makes me feel there is something unseen eating away at the inside of the artistic Apple.

Money is certainly not the ostensible problem. At Sotheby's sale mainly of Impressionist and post-Impressionist paint- ings which I attended here on 9 May, virtually every individual sales record was broken save that of the highest price for a single work. Over $204 million was real- ised, a figure approaching double the previous highest total reached last month at Sotheby's, London. At $47.9 million, Picasso's early self-portrait became the second highest-priced work ever, after Van Gogh's 'Irises'. In the words of the auc- tioneer, as prices leapt up in increments of up to $2 million, 'This is what it's all about.' In the euphoria of the moment, few in the audience would have dreamt of disabusing him. Perhaps most knew no better, nor yet anything of the lives of the artists for whose often minor works they were willing to part with so much mazooma.

One does not wish to sound sanctimo- nious, yet a few reflections on the perils of money-dominated culture might not be inappropriate, especially in these parts. The values inherent in great art provide us with an alternative to and refuge from the venal. Indeed, any attempt to reduce art to the level of merchandise is a denial of the uncompromising processes of thought which should go into the making of it. At one time major collectors and dealers still felt deeply for the treasures under their temporary control. Today one suspects these are increasingly becoming seen mere- ly as the ultimate in designer wallpaper. It is a pity that some petty test of art- historical knowledge cannot be made a condition for the ownership of master- pieces. From the appearance and conversa- tions of many present at this week's series of great auctions here I doubt whether too many would pass it.

Last week's sale of Impressionist and modern works at Christie's, New York broke several records also, and one cannot help thinking that notional catalogue esti- mates are playing a part in this process, for they have come to be viewed now as accurate indications of value. Bidding was often wildly inconsistent with the merits of individual paintings by the same artist. One of the week's most interesting Pissar- ros (of Le Havre) fetched far less than lesser-seeming works. The reason? A fac- tory chimney in the background, which might remind buyers of the true sources of their wealth.

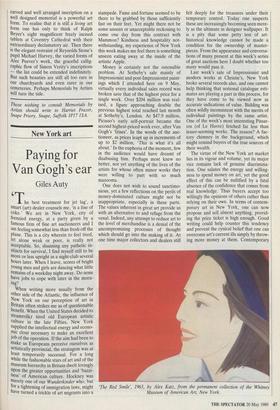

The virtue of the New York art market lies in its vigour and volume, yet its major vice remains lack of genuine discrimina- tion. One salutes the energy and willing- ness to spend money on art, yet the good effect of this can be nullified by a fatal absence of the confidence that comes from real knowledge. Thus buyers accept too willingly the opinions of others rather than relying on their own. In terms of contem- porary art in New York, one can now propose and sell almost anything, provid- ing the price ticket is high enough. Good writing could help counter this tendency and prevent the cynical belief that one can overcome art's current ills simply by throw- ing more money at them. Contemporary 'The Red Smile', 1963, by Alex Katz, from the permanent collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. art here is still bedevilled by the notion of Paying for Van Gogh's ear — feelings of residual guilt about the treatment of major talents in the art-historical past. The latter paralyses present will and turns the condi- tion of contemporary art here into a destructive lottery.

The other day I followed a posse of rich American matrons on their conducted tour of the Whitney Museum of American Art. `The poin of this- picksher', droned the guide in control, 'is whether you see the blue infrunner the yeller, or the yeller infrunner the blue.' I wept for the decent folk who accepted this garbled gospel so humbly. The Whitney is host at present to a biennial show of what is supposed to be work of the best and brightest of the coming generation of American artists. On the evidence of this show, which I will describe in detail next week, the ship of art here is rudderless and sinking. An apoca- lyptic rainstorm accompanied my visit and, as I emerged into the continuing deluge, a smiling negro was consoling his friend. `Rain's only water, man,' he said. If only the ills of this city's art climate could be explained so simply.

Previous page

Previous page