Exhibitions

Masterworks from the Louise Reinhardt Smith Collection (Museum of Modern Art, New York, till 22 August) Picasso and Drawing (PaceWildenstein, New York, till 2 June)

Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Innovator (The Jewish Museum, New York, till 16 July)

New York, New York!

Richard Shone

Te New York art world, though con- centrated on a few patches of the city, has immense variety and beneficial overlap. It is rare to have to leave Manhattan itself to see something exceptional or 'not to be missed'. There's an interlocking grid of artists, dealers, writers, curators, collectors, auctioneers, criss-crossed by hangers-on, `characters', professional party-goers and the occasional certifiable loony.

Visitors from abroad can skim the cream in a few days, running from Museum Mile through the dealers piled on top of each other in the East 70s and 50s down to SoHo and the Village. Uptown museum and gallery gossip whirls around prices, collectors, bequests and promised gifts; downtown, around new spaces and who's moved into which loft. Sleazeball sec- ondary dealers with well-thumbed trans- parencies whisked out of briefcases mingle with Fifth Avenue dowagers (male and female) at receptions and sales; red carpets and stretch limos greet out-of-town collec- tors whose visits put all of life on hold; downtown, readings, performances and openings are packed; critics and curators lunch each other to death. Saturday in SoHo, its galleries open .all day, still attracts huge crowds, though old-timers complain of the shift in atmosphere now that the bridge-and-tunnel element feels at home there. For those in the art world, however, Saturday is the time to trawl the shows, pick up gossip, exchange bitcheries and generally refurbish their image.

In late April and early May, the art scene almost burst its banks. Though the effects of the slump continue CI just want to see some old-fashioned green paper money,' wailed one dealer at the zany art fair held in the bedrooms of the Gramercy Park Hotel), activity was frenetic: big sales on view, swarms of European dealers, spring gallery openings and — what makes it all worthwhile — terrific things to see in both public and commercial spaces — Warhol, Rubens, Gorky, Serra, Dutch landscapes, Nauman and photographs by Nadar.

Mrs Louise Reinhardt Smith is a grande dame of the Museum of Modern Art — a trustee for three decades — and an intrepid collector. Nearly 40 works from her private collection, all gifts or promised gifts to MoMA (save a Braque and a Monet already handed over to the Metropolitan) have just gone on show there with a fanfare of grovelling obei- sance. And why not? Although her collec- tion cannot be classed with the great ones that have enriched American museums in the past — Bliss Cone, Whitney, Thannhauser, etc. — Mrs Smith's has its share of masterpieces and a rump of more modest, interesting works. No one visiting the New York galleries should miss it. It ranges from Degas, Rodin and Redon through early Fauvism to two little Moores of 1956. The undisputed stars are Kandin- sky's large, electrifying 'Picture with an Archer' (1909) and two monumental Picas- sos, 'Bather' of 1908-9, and 'Woman Dressing her Hair' of 1940. The late Monet water-lilies reaches for top C as does Matisse's 1911 'Still Life with Aubergines', a certain sketchiness preventing it, for this writer at least, from hitting the note.

Mrs Smith's is the type of collection formed on strong likes and dislikes and a dose of good advice. What makes her col- lection a cut above many others is a pen- chant for difficult or unusual works. Take, for example, the two Degas coloured tnonotypes. They're not dancers or horses or scenes in the salle de bain; not even brothel interiors. Instead she has chosen two unpeopled landscapes, verging on the abstract, from the unique group made by Degas c. 1890. Her great Picasso of 1940 is of the kind that made the artist the butt of every cartoon about modern art — an over life-size, galumphing, pot-bellied woman with all the charm of an encounter in Jurassic Park. But it is an outright master- piece and says more about war and the Fall of France and Picasso's pessimistic state than any nobly conceived battle-scene. Mrs Smith's works on paper by Picasso show another side of the artist. The watercolour `Meditation' reveals the young painter's consummate draftsmanship and a delicacy, if not serenity, of feeling in its depiction of himself contemplating his sleeping mistress Fernande.

If the • Smith collection whets your appetite for Picasso then walk over to PaceWildenstein to see 'Picasso and Draw- ing'. It is an astonishing assembly of works on paper (with some oil paintings) dis- played on two floors of this prestigious gallery, and worthy of a museum showing. It may not have a rigorous thematic raison d'être and swoops unevenly through Picas- so's career from 1903 to 1970 but it con- tains sensational public and private loans as well as works for sale. There is some- thing to suit all tastes, from harsh to lyrical, tender to bawdy, grand to miniaturist, and everything to confirm Picasso's status, early, middle and late, as one of the two or three greatest draftsmen. All the way through, each exhibit has a definite point to it. Picasso tries something new, explores a theme, makes a final statement, surpasses an earlier treatment, makes great jumps in the compression or loosening of forms. Continually ticking away, his sense of con- struction endows even the slightest motif with a purpose, as though everything was part of some massive transformation of the world.

Up at the top of Museum Mile, in an extravagant mansion at the corner of 92nd Street and Fifth Avenue, is the Jewish Museum. Recently refurbished and now excellently appointed, it has attracted good exhibitions of late and is currently host to Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Innovator, with nearly a hundred paintings and draw- ings covering all phases of the artist's career.

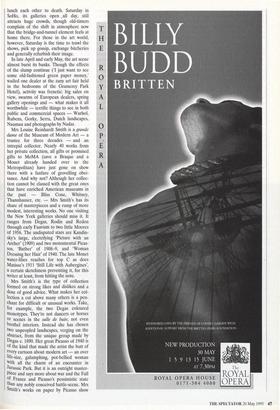

A good number of people yawn at the mention of Pissarro and it is true that there are soporific moments in his 40 or so years of production. He had neither the immedi- ate sensuous charm of Renoir, the perfectly judged lyricism of early Sisley nor Monet's `Meditation (Contemplation); by Pablo Picasso, late 1904. vigorous appetite. Yet he remains a colos- sal figure, a bridge between Corot and the Barbizon landscapists and the prophetic achievements of his friend and proteg6 azanne. Without his early works made in the villages of the Ile de France, without the orchards of Pontoise and the bird's eye views of the Paris boulevards and the Tui- leries, the Impressionist movement would be shorn of a distinct and compelling voice.

Although it must be admitted that there are poor paintings in the show and one or two that make one blush to see ascribed to Pissarro, the selection as a whole gives a representative picture of his development, often through little-known or rarely seen works. Joachim Pissarro, great-grandson of the artist and now chief curator at the Kim- ball Art Museum, Fort Worth, is unusually well placed to secure less familiar paint- ings, often from private collections, to illus- trate Pissarro's adventurous search for personal expression. He was always on the move yet, as seen here, retained an under- lying personality of great consistency frank, modest, grave, a slow but sure exca- vator of the essentials of his chosen theme. He can be clotted, sentimental, can confuse simplicity with naivety, is sometimes mis- guided in his attempts at the erotic. Those who want painterly swish, glamorous sub- jects or an escape from everyday life will leave the exhibition disappointed. But look closely and see what mastery there is in the organisation of figures in his market scenes, what miraculous tonal control informs the spring orchards at Pontoise and the pastures of Eragny. Sickert, who knew Pissarro, commended the artist's `immense and indefatigable laboriousness', labour that was 'cunning, swift and patient'. The exhibition is marked throughout with those qualities of celebration, work and steadfastness of purpose which were also characteristics of Pissarro the man.

Previous page

Previous page