The Slump in Steel

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

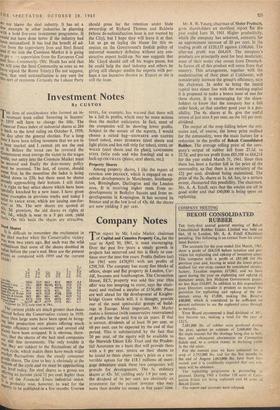

I am not suggesting that the steel industry will altvays work at 95 per cent. of capacity (as in 1960), even, with an expansionist economic policy. It has to plan its capacity well ahead of demand because its production units are vast in size and take years to construct. It has about doubled its output in the fifteen years since the end of the war and it is now engaged on a build- ing programme for new techniques and expan- sion which will bring its capacity to 34 million tons by 1965—about 40 per cent. higher than the 24.3 million tons produced in 1960. It spent £145 million on this programme last year and will spend nearly £200 million this year (perhaps the peak). The Iron and Steel Board, which supervises the industry, has estimated that de- mand in 1965 will be about 28.6 million tons. This is rather less than the estimate of the Iron and Steel Federation, whose Working Party on long-term demand has been in continuous con- sultation with the main consuming industries and the government departments. The Federa- tion's estimate for demand in 1965 is 30 million tons-25 for the home market and 5 for export. The Board thinks that the Federation has over- estimated the home demand. If the Government does not quickly change its economic and mone- tary policy, I would lay a bet on the Board being right.

Before Mr. Lloyd launched his new wages pause the Government's economic policy was conveniently known as `stop-go,' or two years up and two years down. Whenever the labour mar- ket showed signs of inflationary stress Bank rate would be hoisted to a 'crisis' level, bank ad- vances cut, purchase taxes raised and restrictions laid upon the hire-purchase trade in consumer `durables.' The motor trade was always the worst hit and this, unfortunately, is the largest steel-using trade in the country. But apart from these direct attacks upon its customers, the steel industry is vulnerable to a 'crisis' Bank rate be- cause extra dear money tends to start a de- stocking movement. The slump in steel this year is, in fact, ascribed by the Iron and Steel Board to de-stocking. Last year consumers' and mer- chants' stocks increased by over 1 million tons, but in the third quarter of this year, when pro- duction fell by 14 per cent, stocks were reduced by about 250,000 tons. It is not so much the extra financial cost of carrying stocks which starts the down-swing of the stock cycle; it is the bad effect on the businessman everywhere of a 'crisis' Bank rate and a credit squeeze. The heart and confidence go out of his plans for capital spending. So the spending gets cut; stocks are run down; a slump starts and feeds on itself' De-stocking in steel can go on for the next tvio or three quarters—certainly until over, 1 million, tons have been run down. Steel is an index e' the whole economy, for the industry caters f0,1 shipbuilding as well as motors, building as We,!: as household durables, heavy engineering as We° as light, capital as well as consumer goods. The Government should, therefore, take this decline in steel production—now 17 per cent, below the corresponding period of 1960—as warning of an impending domestic slump The latest poll of industrial opinion taken by the, Federation of British Industries confirms the red light. Of the 686 firms replying to this Oen' tionnaire, 51 per cent. reported that they were working below capacity, 35 per cent. that the order books had shortened, 48 per cent. that their production costs had risen, 50 per eert that their profit margins had been squeezed (although 22 per cent. had increased selling prices) and 42 per cent. that lack of orders or sales was keeping output down. To the questio0 whether they felt more or less optimistic abool the general business situation, 44 per cent. these industrial leaders said `less'; only 7 per cent. said 'more.' There is more gloom in Bring! industry today than there has been for years. If a bad domestic recession develops, do not be surprised if the steel industry starts to Post' pone or cut its ambitious expansion programalej A slump, as I have said, feeds upon itself. And do not blame the steel industry. It has set a fine example to other industries in planning With a bold five-year investment programme. It could not have done better if the industry had been nationalised. It has had the benefit of ad- vice from the supervisory Iron and Steel Board and if we join the Common Market it is going to got n e supervision from the European Coal and Steci Community. (Mr. Heath has said that have will join the Steel Community as soon as we nave signed the Rome Treaty.) Do not suppose, th, co, that steel nationalisation is any cure for this sort of recession. Certainly the Labour Party should press for the retention under Stale ownership of Richard Thomas and Baldwin (whose de-nationalisation issue is not wanted by the City), but I hope they will leave it at that. Let us go on laying the blame for this re- cession on the Government's foolish policy of universal monetary deflation without any con- structive export build-up. No one suggests that Mr. Lloyd should call off his wages pause, but he could help the steel industry and others by giving still cheaper credits for exports with per- haps a tax incentive thrown in. Export or die is still the issue.

Previous page

Previous page