A good time for a survey

Elaine Moss

As reviewers of children's books we are in danger of becoming the least important link in the long chain between the author and the Child reader: our influence is felt certainly, but not because parents, teachers and librarians read what we write and order books for their Children on the strength of it, though some, of course, do. It is felt, I am afraid, rather because publishers watch our reception of their fledgings with an eagle eye and subtly, Perhaps even subconsciously, tend to choose, from the thousands of manuscripts they read,

those that the adult reviewer of children's b.00ks is going to admire from an adult

literary standpoint.

The prevalent trend in children's fiction Publishing is (therefore?) towards literary excellence in experimental novels " for teenagers" such p Alan Garner's Red Shift. This is a book which may be within the scope of a highly intellectual sixteen-year-old of Mature emotional experience; it does not, in .!.°Y view, belong on a children's list at all, but it is capturing major review space in children's book columns. We need high quality writing and publishing for the elite Young reader as we need Eton — to set a standard and provide a yardstick against Which reading (and education) for the Majority can be measured. So we shall, and should, go on praising the praiseworthy children's book as literature.

But should we not devote a comparable amount of attention to the story, the not-soliterary hard bite on which younger children cut .their teeth? Might publishers then balance their lists in favour of better narrative fiction for the pre-pubescent? Might some of us gain larger, less specialist audience than we now have?

Unlike the critic of adult literature who sPeaks directly to the potential consumer of 'Ihe book he is writing about, the children's ook reviewer has a responsibility to a middle Man and a third party — that is to say towards the adult who in any capacity is hel,PIng a child to find books and towards the child himself, al every reading stage. Our c, alllng is more difficult (though generally less

olghbrow); it is more demanding, broader in 8, cope; if the trend towards conducting public

out esoteric conversations with authors and Publishers on only the most literary books on children's lists were to become more Widespread, we should gradually lose the opPortunity which newspaper space now gives US, of talking in an altogether different and

more practical key with the people who also matter — parents, teachers and librarians. We are not adult book reviewers manqué. The reviewer of adult books can afford to neglect• the vast mass of people for whom books are blocks. Our concern is with all young people who may one day be readers.

All young people: today that means the immigrant children (English speaking and non-English speaking at whatever age they may have arrived.in this country); it means children who are technically capable of learning to read but whom the education system may abandon illiterate, like so much driftwood, on the shores of adult life; it means the average reader (who is likely to stop reading altogether at about twelve unless parents and techeit can help in motivating him); and it means the gifted reader who is hooked but who also passes through stages when the 'right" book does not readily come to hand.

Some of the trends we notice in children's books are capable of gross misinterpretation unless we see them in the context of present-day young society. Take the flood of cartoon books for example, it is all too easy to dismiss these as comics in stiff covers until one realises the helpful part they play in easing immigrant children at the secondary school level into reading English. Herge's

Tintin series and Simon Stern's Captain Ketchup (both Methuen) are cartoon stories

of high quality which older children can read without feeling humiliated — as they would if they had to learn English through the equally simple text of a toddler's picture book.

The rash of rewritten classics is more difficult to stomach but if it can be seen in the light of a temporary contribution towards quick integration, it appears slightly less heretical. English literary heritage is rich. New young citizens need to catch hold of guide

lines. Jane Eyre and David Copperfield are as much part of the British scene as fish and

chips. Is it then altogether reprehensible to issue a series of retold classics in which all that is left of the author's oeuvre is an emasculated story? Because there is a danger that children perfectly capable of reading Bronte and Dickens will find these brittle skeletons and substitute them for the weighty-looking novels which bear the same names, the whole question of filleted classics is something we should be discussing fully on children's book pages.

A huge proportion of the books the visitor

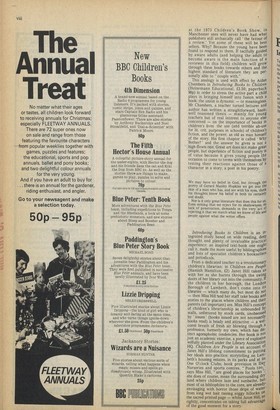

at the 1973 Children's Book Show, in Manchester sees will never have had what publishers still archaically call 'the favour of a review.' Yet some of these will be best sellers. Why? Because the young have been found to respond to them. If tactfully guided by aware adults (and helping theadult to become aware is the main function of a reviewer in this field) children will groW through these books towards others and the highest standard of literature they are personally able to "couple with."

This analogy is used with effect by Aldan Chambers. in Introducing Books to Children (Heinemann Educational, £2.50; paperback 90p) in order to stress the active part a child plays in bringing himself into fusion with a book: the union is dynamic — or meaningless. Mr Chambers, a teacher turned lecturer and author has written a straightforward, basic, well reasoned thesis — mainly for young teachers but of real interest to anyone else concerned — on the importance of books In children's lives the use (add terrible abuse for lit. crit. purposes in schools) of children's fiction, and the power, as old as man himself of the story. His first chapter is called WhY Bother?' and the answer he gives is not a high-flown one. Great art does not make great people, but experience of fiction and poetry IS of value because it gives young people the occasion to come to terms with themselves bY testing their reactions against those of a character in a story, a poet in his poetry: We may have no belief in God, but through the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins we get into the skin of a man who has, and see with his eyes, think his thoughts, know his belief in both its certainlY and doubt.

Nor is it only great literature that does this for us. Even writing that we reject for its shallowness, its, lack of penetration, demands in the very' act 01 rejecting it that we match what we know of life an° people against what the writer otters.

Introducing Books to Children is an in' tegrated study based on wide reading, deeP, thought and plenty of invaluable practical experience: an inspired text-book one might call it, made the more useful by bibliographies and lists of specialist children's booksellers and periodicals.

From a dedicated teacher to a revolutionarY children's librarian: in Children are People (Hamish Hamilton, £2) Janet Hill takes us with her as she bursts through the swill, doors of her library out into the community, if the children in her borough, the London Borough of Lambeth, don't come into its libraries — which many do, but most do no;

then Miss Hill 'and her staff take books and stories to the places where children and their parents (all important) are. Miss Hill's concept of children's librarianship as unbounded bY, walls, unfettered by stock cards, unobsessea by ' issues ' (books issued are not necessarilY

books read) is heady and attractive a Wel' come breath of fresh air blowing through a profession, formerly my own, which .has dis' tinct agoraphobic tendencies. Her book is not just an academic exercise, a piece of explosive wilfully planted under the Library Association HQ. Children Are People is an account of Janet Hill's lifelong commitment to putting her ideals into practice: storytelling on La" beth's housing estates, in its parks and at its One O'clock Clubs; book provision in Dat Nurseries and sports centres. " Pools too.: says Miss Hill, "are good places for books ' ,

. she does of course, mean the surrounding drY land where children laze and sunbathe, butt most of us bibliophiles to the core, are alreadY' envisaging with horror those drips of water' from long wet hair raising soggy hillocks on the sacred printed page — whilst Janet Hill, sn rightly, concentrates on taking full advantage of the good moment for a story. she does of course, mean the surrounding drY land where children laze and sunbathe, butt most of us bibliophiles to the core, are alreadY' envisaging with horror those drips of water' from long wet hair raising soggy hillocks on the sacred printed page — whilst Janet Hill, sn rightly, concentrates on taking full advantage of the good moment for a story.

Previous page

Previous page