Eyeball to eyeball with reality

Mary Wakefield quails at Shackleton's adventures on the giant Imax screen Vast swells of green-black sea-water rolled around us, solid-seeming and bevelled like beaten metal. To left and right, cliffs of glacial Antarctic ice hundreds of feet high glowed blue against a sky the colour of dirty snow, Shamefully, I felt sick. My stomach seesawed and I had to turn my head and stare hard at the unmoving green exit lights above the doors of the British Film Institute's London Imax cinema at Waterloo. The story of Sir Ernest Shackleton's disastrous but heroic expedition to cross the Antarctic is impressive in print. Re-enacted, filmed and projected on a 65ft screen, it is awesome.

The advertisement through which Shackleton recruited the 27 crew members who set sail with him in the Endurance in 1914, bound for the Antarctic continent, read as follows: 'Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages. Bitter cold. Long months of complete darkness. Constant danger. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.'

Six weeks into their journey, the wooden ship, which took its name from the Shackleton family motto Fortitudine Vincimus — 'by endurance we conquer' — was itself conquered. Frozen in and trapped by the ice, the crew waited out the winter. But when the long-anticipated, warmer weather came and the pack ice began to move, instead of freeing the Endurance, it crushed her. So more than a year after first embarking on his expedition to cross the Antarctic, Ernest Shackleton divided his men into three lifeboats and set off once again with a new and even more far-fetched ambition: to save every life.

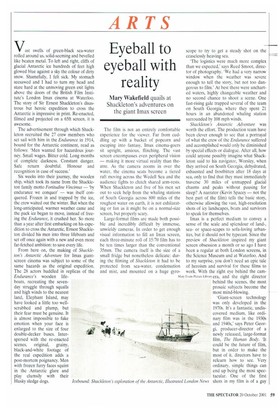

From here on, the making of Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure for Imax giantscreen cinema was subject to some of the same hazards as the original expedition. The 28 actors huddled in replicas of the Endurance's wooden lifeboats, recreating the sevenday struggle through squalls and high winds to the nearest land, Elephant Island, may have looked a little too wellscrubbed and plump, but their fear must be genuine. It is almost impossible to fake emotion when your face is enlarged to the size of four double-decker buses. Interspersed with the re-enacted scenes, original, grainy, black-and-white footage of the real expedition adds a post-mortem poignancy. Men with frozen furry faces squint in the Antarctic glare and play clumsily with their Husky sledge dogs.

The film is not an entirely comfortable experience for the viewer. Far from cuddling up with a bucket of popcorn and escaping into fantasy. Imax cinema-goers sit upright, anxious, flinching. The vast screen encompasses even peripheral vision — making it more virtual reality than theatre. As the camera zooms in over the water, the cinema seats become a tiered raft moving across the Wedell Sea and the audience fights to clutch shared arm-rests. When Shackleton and five of his men set out to seek help from the whaling stations of South Georgia across 800 miles of the roughest water on earth, it is not exhilarating or fun as it might be on a normal-size screen, but properly scary.

Large-format films are made both possible and incredibly difficult by immense, unwieldy cameras. In order to get enough visual information to fill an Imax screen, each three-minute roll of 15/70 film has to be ten times larger than the conventional 35mm. The camera itself is the size of a small fridge but nonetheless delicate: during the filming of Shackleton it had to be protected from sea-water, condensation and mist, and mounted on a huge gyro scope to try to get a steady shot on the ceaselessly heaving sea.

'The logistics were much more complex than we expected.' says Reed Smoot, director of photography. -We had a very narrow window when the weather was severe enough to tell the story, but not too dangerous to film.' At best there were uncharted waters, highly changeable weather and no second chance to shoot a scene. One fast-rising gale trapped several of the team on South Georgia, where they spent 21 hours in an abandoned whaling station surrounded by 108 mph winds.

Shackleton 's Antarctic Adventure was worth the effort. The production team have been clever enough to see that a portrayal of what the crew of the Endurance suffered and accomplished would only be diminished by special effects or dialogue. After all, how could anyone possibly imagine what Shackleton said to his navigator, Worsley, when they arrived on South Georgia, dehydrated, exhausted and frostbitten after 18 days at sea, only to find that they must immediately traverse 30 miles of unmapped glacial chasms and peaks without pausing for sleep? A narrator (Kevin Spacey — not the best part of the film) tells the basic story, otherwise allowing the vast, high-resolution shots of icy landscapes, boats and survivors to speak for themselves.

Imax is a perfect medium to convey a sense of the scale and splendour of land-, seaor space-scapes to sofa-loving urbanites, but it should not be typecast. Since the preview of Shackleton inspired my giant screen obsession a month or so ago I have been a regular at both London screens, in the Science Museum and at Waterloo, And to my surprise, you don't need an epic tale of heroism and survival for these films to work. With the right eye behind the cam

Mary Evans Picture Library era, and the right director behind the scenes, the most prosaic subjects become the most mind-blowing.

'Giant-screen technology was only developed in the 1970s. It's a fantastic, undiscovered medium, like ordinary film was in the 1930s and 1940s,' says Peter Georgi, producer-director of a newly released, large-format film, The Human Body. 'It could be the future of film, but in order to make the most of it, directors have to relearn how to see. Very ordinary, simple things can end up being the most spectacular. One of the first shots in my film is of a guy shaving, something most of the audience had seen hundreds of times before. But because it was from such a different, very close-up perspective, with hairs the width of post-boxes and such an intense rasping sound, everyone gasped.'

Georgi's film exemplifies how !max can make the mundane miraculous. It opens with a sweep of the camera over a woman's body. The shot is close up but so clear that each tiny crease is a deep crevasse and the skin tics and pulsates as if it were an animal independent of the brain. Like tiny parasites, viewers are taken up the neck, across two giant segments of pulpy lip, and, after a pause to eyeball a 65ft iris, we fly fast, straight into the pupil and through to the back of the optic nerve. I had the same sense of awe and fascination that I felt looking out of the window on my first aeroplane flight.

As with Shackleton, The Human Body is a documentary, the format best suited to so large a screen. The complicated narrative and character development necessary for fictional drama is impossible with a six-storey image. Imagine, for instance, filming a simple, romantic scene of a girl and a boy, sitting facing each other in a café. On an Imax screen, there is no getting round the fact either that the actor's heads are each the size of a house making it difficult to focus on the shot as a whole, or that they are in the middle distance, and pretty indistinguishable from the other customers.

So documentaries it is, but don't let the word put you off. Because an Imax screen becomes your entire field of vision, it's a much more visceral experience than television. When the credits roll, you don't just murmur, 'How interesting, I must tape part 2', and wander off to make cocoa. Nor do you blink and shake your head to bring yourself back to the present, as when leaving a conventional cinema. The audience emerges energised and excited, as if they have somehow taken part.

For obvious reasons, it's incredibly difficult to find the money to fund a large-format film. There are only six Imax cinemas in the UK, and just over 200 worldwide. Financial backers accustomed to Hollywood blockbusters are hardly going to leap at the chance to sponsor a movie that will break even only after three years. They should.

'There's so much you can do with Imax,' explains Georgi. Tor instance, what large format is particularly good at is capturing a moment of reality. An Imax photographer shot Nelson Mandela's inaugural speech when he was made president. It was just one static shot, but it was electrifying. One of the most obvious ways to realise the potential of large-format film is to use it as archive. Imagine if we'd captured the most powerful, entertaining or important moments of our time on Imax — Elvis's last concert, Churchill, Diana's funeral, or even the World Trade Center disaster — and put them all together. Some things might be too distressing to look at immediately, but our great-grandchildren would be able to have a sense of actually being in our time. It might not be a project that someone looking for an immediate profit would want to endorse, but what a wonderful gift to future generations.'

Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure opens on 19 October at the bfl London Imcvc cinema at Waterloo.

Previous page

Previous page