ALARMING STATE OF THE COUNTRY.

THE journals called Ministerial (one of those titles of courtesy never claimed of right, but accepted with tacit modesty by those whom the public voice honours with the distinction) have lately permitted themselves a latitude of political disquisition which we find hard to reconcile with the presumed discretion of Treasury organs, or with those notions they desired us to form of the disci- pline of the DUKE of WELLINGTON'S Government. They are after all, we suspect therefore, only volunteers in the cause, whom the posterior influence of that discipline, if it was ever applied to them, has been unable to hinder from indulging in the established licence of partisanship in making war, now and then, on their own ac- count. To this free-service system it is, we are persuaded, that we owe the melancholy descriptions of the present condition of the country, and their gloomy forebodings of a more disastrous future, which the infection of Liberalism, according to the Morning Post —the march of Catholicism, according to the Standard—and the extinction of one-pound notes, according to the New Times—are preparing for this once happy land.

" It is a most extraordinary fact (says the last-named paper), that while capital is unemployed—the rents of the landowner in arrear—the farmer struggling with embarrassments—the manufacturer contending with foreign competition, and complaining of inadequate profits—the shipowner almost bankrupt—the glove-trade in ruin—thousands of arti- sans unemployed, and a law compelling us to return to a metallic cur- rency when gold is going out of the kingdom—it is strange, we say, under these circumstances, that the journals should be instructed to inform us that the country is in a flourishing arid desirable condition."

That this delusion shall no longer exist, however, the New Times has taken ample care. With exemplary patience and dili- gence it goes over again the consideration of our national resources and embarrassments ; it discusses the currency question ab ovo ; column after column is poured upon its readers, till amazement and alarm confound their faculties, and they discover, thoughtless beings! that they are "at the same instant treading on a charged mine, walking among trap-doors, and letting off' squibs in the pre- cincts of a powder-magazine." Our safety lies, in this hour of danger and difficulty, in repealing the law which prohibits, after April next, the circulation of small notes. What is it that Whigs and Liberals have been ejected from the Cabinet, if we are still threatened with a gold currency ? We support his Majesty's Mi- nisters, but our trust is in the country bankers. They are the pro- moters of industry, the distributors of wealth, and the guardians of credit. Look at the services rendered to the country by these "injured, slandered" " In the distant parts of the kingdom it was to the neighbouring banker that the farmer looked for assistance in a bad season—the manufacturer in a gloomy period—the tradesman of slender means, but industrious ha- bits, when he wished to extend his business and increase his profits. To him alone did these persons look for relief in the hour of embarrassment. In the prosperity of these useful individuals the country banker had a deep interest ; he was identified with their trade, their industry, their speculations—he was the guardian of their credit, the protector of their interests, and the conservator of their integrity in all the relations of business. The banker had a deep stake in the improvement of manu- factures and agriculture, in benefiting the town or hamlet where he re- sided, or the district where he possessed an estate."

Take from him only the liberty of accommodating people with the loan of notes under five pounds, and all this ceases. He may lend gold, and large notes, but no ! his stake is gone; his interest in the welfare of the country terminates ; "bad seasons," "gloomy periods," and "slender means," appeal to him in vain; and we may play out the game of" speculation without him as we best can.

The New Times defends the country banker from "one most audacious imputation," namely- " that their monetary system has been the cause of what is called high prices. There never was a more unfounded charge than this. High prices in this country have been produced by enormous taxes —by heavy burdens of every kind—by the immense numbers of persons who are supported in indolence at the expense of the labourer and the

capitalist. The country bankers have had no more influence in forming these prices than steam-engines had in producing the rains of last sum- mer. The expansion and contraction of their issues may have been the apparent cause of rises and falls in prices and wages. But this is but a secondary cause. They neither can increase nor diminish their issues but according to the wants of commerce and trade. If trade is prosper- ous, pecuniary transactions must be numerous and rapid—the circulation must be increased in force as well as in quantity—and they, the country bankers, have neither the power to increase nor the power to retard them. They only meet the demand—they only yield the credit that is required— they only administer to the necessities of the trader and manufacturer— and they can administer neither more nor less than the trader and manu- facturer require and can fairly demand."

Hums, in one of his Essays, supposes the case of a currency consisting exclusively of paper, and of every man in this kingdom rising on a given morning with double the amount of bank-notes in his possession that he could command the night before ; and he shows that such an increase of the circulating medium would not make any man richer than he was, but would merely double the prices of all commodities in the country. We would ask the New Times to suppose that increase produced by the very natural operation of the country banker administering to the assumed neces- sities of the farmer, trader, and manufacturer, instead of by magic, and to say in what respects the effects on prices would differ ?

The " imputation," however, receives another answer :—

" But even admitting that they were a concurrent cause of high prices, why should they be censured for what is beneficial ?"

Why indeed!

"Is there a man so dolted—so blind—so prejudiced—so ill-informed, as not to know that it is not high prices, but low prices, which at this moment press so much on all the great interests of the country—which have rendered the soil in many places not worth the cultivating—which have reduced our agricultural labourers to the condition of poachers and paupers, and have converted our artisans into the most wretched, ill-fed, ill-clothed, needy, demoralized, and debauched class of vagabonds that the sun ever shone upon. What can we gain by low prices but the poverty, and serf-like habits, and moral and physical degradation, of the people of Pomerania? When were all classes of men in this country in the must flourishing and 'enviable' state, but when prices were high ? And when -were they otherwise—when were soup kitchens in every street of Bir- mingham, Manchester, and Paisley,—but when prices were low ?

'‘ These are memorable facts which ought to be borne in mind and oftener adverted to. If the country bankers have contributed to raise prices, then do they deserve more of our gratitude. We never were poor and distracted—never were we a declining country while the wages of la- bour were high—the price of the quartern loaf high—the price of our coats, boots, bacon, and cream and cheese, equally high. We never were otherwise than a nation of paupers and bankrupts when these wages and prices were low."

If we are poor and distracted,—a nation of paupers and bank- rupts—because prices are low ; if we were in a flourishing and enviable state, when prices were high ; and if the country bankers have had no more influence in raising prices than steam-engines have in producing rain ; we would inquire of our contemporary, what benefit the country reaps from the circulation of their notes, and why the extinction of them all, above and under five pounds, should consummate our ruin ?

It is a generally-received opinion that very low prices have a direct tendency to promote an export trade, and thus to restore the equilibrium in marketable value that has been disturbed by any of those influences of which commerce is so susceptible. But the paper from which we quote has cut off this resource. The state- ments with which it furnishes us are singular, as exhibiting an ex- traordinary fluctuation in our commercial transactions with foreign markets, though the writer has omitted to inform us in what way the present falling off in our exports produced the low prices under which we are suffering in our home trade. He can scarcely attribute it to. high prices ; which are a benefit to the nation that possesses them—and which are gone from us with the small notes.

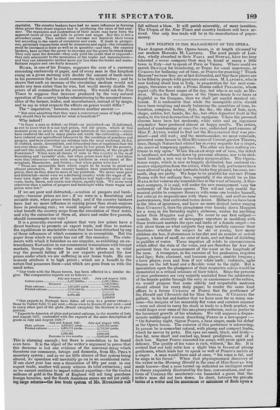

"Our trade with the Hanse towns, has been affected in a similar de- gree. The comparative exports

July Cotton yarns Decrease Plain calicoes..

Printed calicoes.

Decrease

are as follows :— and August 1827. July and August 1828.

2,427,9681bs 1,287,7491bs. .... . 1,140,2191bs. '

I 074,051 yards 966,118yds.

2,735,384 do. . 1,594,698 do.

3,809,435 . ..... ....... 2,560,816 1,248,619

"Our exports to Portugal have fallen off even to a greater extent— those to Turkey fully 75 per cent.—those even to Russia 25 per cent.—and to every other part of the globe (Brazil excepted) the decrease is in pro- portion.

"Exports to America of plain and printed calicoes, in the months of July and August 1827, contrasted with the exports of the same description of goods in July and August 1828 :"

July and August 1827. July and August 182S. Plain calicoes 2,528,617 yards. . 1,236,353 yards. Printed calicoes . 5,301,775 yards ..... 2,712,153 yards.

7,829,492 3,948,506

Decrease in two mouths ......3,880,085 yards.

This is alarming enough ; but there is consolation to be found even here. It is the object of the writer's argument to prove that this decrease is but one evidence of the universal decay which threatens our commerce, foreign and domestic, from Mr. PEEL'S monetary system ; and as we see little chance of that system being altered, its operation will inevitably go on in an accelerated ratio. If one short year has seen a diminution of fifty per cent, in our export trade, another will surely witness its total extinction ; and as we cannot continue to import without exporting—for the twelve millions of gold in the Bank of England will not long purchase foreign luxuries, and the South American mines are not yet yield- ing large returns.the free ,tracle system of Mr. Husitissort will fall without a blow. It will perish miserably, of mere inanition. The Utopia of the New Times and country bankers will have ar- rived. Our only free trade will be in the manufacture of paper- money.

Previous page

Previous page