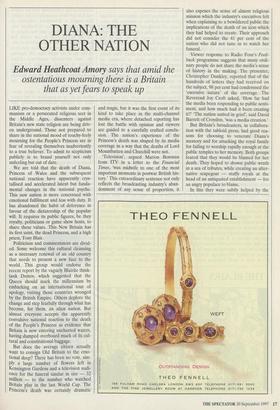

DIANA: THE OTHER NATION

Edward Heathcoat Amory says that amid the

ostentatious mourning there is a Britain that as yet fears to speak up

LIKE pro-democracy activists under com- munism or a persecuted religious sect in the Middle Ages, dissenters against Britain's new state religion are being driv- en underground. Those not prepared to share in the national mood of touchy-feely mourning for the People's Princess are in fear of revealing themselves inadvertently to a true believer. To admit to scepticism publicly is to brand yourself not only unfeeling but out of date.

We are told that the death of Diana, Princess of Wales and the subsequent national reaction have apparently crys- tallised and accelerated latent but funda- mental changes in the national psyche. This new nation is more concerned with emotional fulfilment and less with duty. It has abandoned the habit of deference in favour of the dictatorship of the popular will. It requires its public figures, be they royalty, politicians or game show hosts, to share these values. This New Britain has its first saint, the dead Princess, and a high priest, Tony Blair.

Politicians and commentators are divid- ed. Some welcome this cultural cleansing as a necessary renewal of an old country that needs to present a new face to the world. This group would endorse the recent report by the vaguely Blairite think- tank Demos, which suggested that the Queen should mark the millennium by embarking on an international tour of apology, visiting those countries wronged by the British Empire. Others deplore the change and step fearfully through what has become, for them, an alien nation. But almost everyone accepts the apparently convulsive national reaction to the death of the People's Princess as evidence that Britain is now entering uncharted waters, having dumped overboard much of its cul- tural and constitutional baggage.

But does the average citizen actually want to consign Old Britain to the emo- tional deep? There has been no vote, sim- ply a large number of flowers left in Kensington Gardens and a television audi- ence for the funeral similar in size — 32 million — to the number who watched Britain play in the last World Cup. The Princess's death was certainly dramatic and tragic, but it was the first event of its kind to take place in the multi-channel media era, where detached reporting has lost the battle with opinion and viewers are guided to a carefully crafted conclu- sion. The nation's experience of the Princess's death was shaped by its media coverage in a way that the deaths of Lord Mountbatten and Churchill were not.

`Television', argued Marion Bowman from ITV in a letter to the Financial Times, 'was midwife to one of the most important moments in postwar British his- tory.' This extraordinary sentence not only reflects the broadcasting industry's aban- donment of any sense of proportion, it also exposes the sense of almost religious mission which the industry's executives felt when explaining to a bewildered public the implications of the death of an icon which they had helped to create. Their approach did not consider the 41 per cent of the nation who did not tune in to watch her funeral.

Viewer response to Radio Four's Feed- back programme suggests that many ordi- nary people do not share the media's sense of history in the making. The presenter, Christopher Dunkley, reported that of the hundreds of letters they had received on the subject, 98 per cent had condemned the `excessive nature' of the coverage. The Reverend Joy Croft asked, 'How far had the media been responding to public senti- ment, and how much had it been creating it?' The nation united in grief, said David Barrett of Croydon, 'was a media creation.'

But Britain's broadcasters, in collabora- tion with the tabloid press, had good rea- sons for choosing to venerate Diana's memory and for attacking the royal family for failing to worship rapidly enough at the public temples to her memory. Both groups feared that they would be blamed for her death. They hoped to drown public wrath in a sea of tributes, while creating an alter- native scapegoat — stuffy royals at the head of an antiquated establishment — for an angry populace to blame.

In this they were subtly helped by the Prime Minister, Tony Blair. Mr Blair has, consciously or unconsciously, harnessed the dead Princess to his crusade for mod- ernising British institutions. Although he did act to support the royal family, he also secured an unprecedented mandate to force change on an institution which would otherwise have shunned it. He has man- aged to create a link in the public mind between New Labour, as recently endorsed at the ballot-box, and New Britain, as endorsed by the crowds in Kensington Gardens.

Both Mr Blair and the media were able to ignore those who thought that the hyste- ria was getting out of hand. This 'other nation', as an editorial in this magazine described them two weeks ago, was con- strained by a distaste for speaking ill of the dead, combined with the traditional, but now endangered, stiff upper lip. Such considerations did not affect the Princess's hagiographers, who had already erected a verbal shrine to her memory on the nation's airwaves before most Britons had finished their bacon and eggs on that fate- ful Sunday. Unlike the royal family, who not surprisingly retreated in shock to the seclusion of Balmoral, both Earl Spencer and the Al Fayed family chose to retreat only as far as the next press conference, where they both took the opportunity to settle old scores with the paparazzi.

Later, when alternative views might have begun to surface, it became clear that expressions of dissent would not be tolerated. Jim Farry, secretary of the Scot- tish Football Association, nearly lost his job for suggesting that the Scotland- Belarus match should go ahead on the day of the funeral. A magistrate sentenced two women tourists caught stealing cuddly toys from the tributes to 28 days in jail, admit- ting that this was a harsher sentence than might have been expected because 'he had a 'duty' to reflect 'the outrage of the pub- lic'. It took a more balanced judge to impose fines instead.

On a personal level, supporters of Diana have carte blanche to embrace the emo- tional self-indulgence that she stood for. One young London couple, who were hav- ing a wedding party on the day of her death, found that many of their guests did not attend, their excuse being that they had been in a state of shock. Two weeks later, at a stag night in London, an attempt by one guest to tell a very mild joke about the events in Paris was shouted down as tasteless. A BBC comedy produc- er admits that in contrast to the space shuttle crash or Lord Mountbatten's death, no one will tell jokes about Diana `if they value their careers'. The traditional British use of humour as a catharsis in dif- ficult situations has now, apparently, become politically incorrect.

Enthusiasts for this new world argue that the only unbelievers are a bunch of beleaguered toffs, cowering in their cas- tles. But in practice the silent ranks of the sceptics span barriers of age, class, sex and colour. 'I wasn't going to close my stall for her. I didn't know her,' said Dave, a trader in Portobello Road, who was happily sell- ing bric-à-brac on the morning of the funeral. 'I understand children behaving in this way,' said a primary school head- mistress, 'but not adults.'

How many dissenters are there? We have no means of knowing, and even the statistics we do have are of little help. Many of those who watched television on the day of her death, tuned in to the funeral or visited Kensington Gardens were drawn by fascination with this media- driven national convulsion. A straw poll of all the people I have met and talked to over the past weeks suggests that a clear majority feel that reaction to the accident in Paris has gone too far.

Such heretics believe, while feeling enormous regret and sadness at Diana's death, that her status as an icon was a function of her relationship with the media, which is now busy manipulating her legacy. She waged a determined campaign to attempt to prevent her ex-husband suc- ceeding to the throne, and was happy to use the tabloid press to put across her point of view. On her withdrawal from pub- lic life last year, she resigned as patron of all but six of the more than 100 charities she had previously supported. Prince Charles, in contrast, attended 518 public engagements in 1996, the majority devoted to charitable causes, and his own charities raised £20 million for young people, the homeless and the disabled.

Those who have taken it upon them- selves to set up as guardians of her legacy have an equally chequered history. Her brother, Charles Spencer, acquired his hatred of the tabloid press not as a result of its persecution of his sister, but after his own extra-marital affair was exposed by them. Then there is Mohamed Al Fayed repeatedly refused British nationality by the previous government — who admitted to handing over brown envelopes full of cash to Conservative MPs to encourage them to ask questions at his behest in the House of Commons.

So we would be wrong simply to accept that either we emigrate or adjust to life in a new Britain, with a revised set of values which we must adopt to survive. Gradually, if the media will permit it, traditional British sanity will reassert itself. The Mall will remain open, Prince Charles will be seen with Camilla Parker Bowles, Lord Spencer will return to his compound in South Africa, and we may even be able to tell a joke about the whole affair without risking a public lynching. At that point, Mr Blair will have to concentrate on the real political issues, like class sizes and interest rates, and abandon his quest for the fool's gold of a New Labour Jerusalem built on the uncertain foundations of the wreckage in the Pont d'Alma underpass.

Previous page

Previous page