Consuming Interest

Slender Satisfaction

By LESLIE ADRIAN 'But wait a bit,' the Oysters cried, 'Before we have our chat; For some of us arc out of breath, And all of us are fat l' SPREAD out beside me is a selection of advertise- ments cut from the daily papers, trade journals and women's magazines, also an assortment of promotional handouts. I hey all tell the same story (or should I say fairy tale?,)—eat bread and get slim. Not ordinary bread from the baker, but 'crunchy,' lighter,' 'enriched' and 'satisfying' breads, specially pro- cessed, glamorously packaged and expensively Publicised.

The claims are bold: 'Primula Slimbread,' pro- claims a leaflet picked up at the Ideal Home Ex- hibition, 'has a calorific value of only 120 eals./oz., The same proud boast could be made for pure starch. (Eighty per cent. of the dry Weight of white bread is carbohydrate, which puts Primula Slimbread, on the maker's own reckon- ing, only a nose ahead in the starch reduction stakes.) The leaflet romps on to the declaration that 'from analysis, it will be seen that Slimbread IN a complete food.' I am assured by a leading nutritionist that anyone who actually took that claim at its face value, and ate nothing else, would soon be a fascinating case study in at least half a dozen deficiency diseases. Procea, makers of Slimcea, take a more re- strained line. Their point is made with diet charts, sample menus and illustrated with the silhouette of a maiden who looks ready for any- thing, including the leading role in Round the World with Nothing On. Ryvita 'helps me to keep slim,' says Julie Andrews, propped prettily against a jumbo packet of crispbread. 'Vita-wheat is non-fattening too,' declares a shapely sylph in a bath towel; and the Slimbread sweetie, from inside her symbolic hour-glass, tells the gullible about 'the satisfying way to slim.'

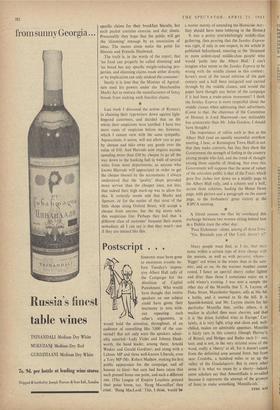

Perhaps the chart below, given to me by Professor John Yudkin, Head of the Nutrition Department at Queen Elizabeth College, will put the advertised claims of these so-called slimming breads into perspective. The exaggerations are so neatly exposed.

Advertised claims such as these, which are de- liberately misleading, have been under heavy fire lately. The proprietary medicine men have always been a popular target and recently it has been the turn of the washing-powder puffers, who were hauled up for breaking the command- ment 'Thou shalt not run down a competitor'— and great claims to ethical sensitivity were made- in the process. Now, the Advertising Inquiry Council (newest weapon in the consumer-pro- tection arsenal) have been pressing the Minister of Agriculture to clamp down on firms which make spurious claims for their rolls, rusks and breads. It was the recommendations in an out- spoken report on bread and flour (published last November by the Food Standards Committee) that prompted the AIC to agitate for govern- ment interference.

The collective mind of the Food Standards Committee seems to have been quite clear on this subject. They disapproved of any special description or, claims being allowed for breads with a protein content of less than 21 per cent., but agreed that it was reasonable for those with a higher protein content to call themselves 'high protein' breads.

The Committee recommended that any claim to be starch-reduced should be restricted to breads where the carbohydrate content had been reduced to less than 50 per cent. by weight compared with ordinary bread. Only four pre- parations measure up, or rather down, anywhere near this standard. Energen Crispbread (the only genuinely starch-reduced crispbread), Energen Rolls, Granose and Figgerrolls. (The last two are both rolls, similar in composition to those made by Energen.) The Committee also would like to see pro- hibited any advertisement which suggests that certain types of bread have inherent weight- reducing properties. The word 'suggests' is the crucial one here.

For instance, Huntley and Palmer make no specific claims for their breakfast biscuits, but each packet contains exercise and diet sheets. Presumably they hope that the public will get the 'slimming' message by an association of ideas. The names alone make the point for Slimcea and primula Slimbread.

The truth is, in the words of the report, that `no food can properly be called slimming' and `no bread has any specific weight-reducing pro- perties, and slimming claims made either directly or by implication can only mislead the consumer.'

Surely it is time that the Minister of Agricul- ture used his powers under the Merchandise Marks Act to restrain the manufacturers of fancy breads from making such fanciful claims.

Last week I discussed the action of Ryman's in chaining their typewriters down against light- angered customers, and decided that on the whole their suspicions were justified. 1 have two more cases of suspicion before me, however, which I cannot view with the same sympathy. Aquascutum, it seems, will not allow you to pay by cheque and take away any goods over the value of £10. And Harrods now require anyone spending more than £10 by cheque to go all the way down to the banking hall (a walk of several miles from most departments, as anyone who knows Harrods will appreciate) in order to get the cheque blessed by the accountants. I always understood that the 'quality' shops provided more service than the cheaper ones, not less; that indeed their high mark-up was to allow for this. It certainly seems odd that Marks and Spencer, or for the matter of that most of the little shops along Oxford Street, will accept a cheque from anyone, but the big stores take this suspicious line. Perhaps they feel that 'a different class of customer' frequent their stores nowadays; all I can say is that they won't—not if they are treated like this.

Previous page

Previous page