The way we live now

Richard West

The financier Augustus Melmotte, the central character in The Way We Live Now, is described by Trollope himself as a 'horrid, big, rich scoundrel'. There are plenty of other villains in this book but none of them, even those who most brazenly sponge on him, says a kind word for Mr Melmotte. Everybody in London, a hundred years ago, knows that Mr Melmotte is a swindler, yet none ever question that he is actually rich, that he can lay his hands on cash. This is the more surprising since nobody quite knows who Mr Melmotte is, or how he made his money.

Trollope reveals from the start that Mr Melmotte has made his money in France and indeed actually called himself Monsieur Melmotte before deciding to make a second career in England. We also learn from the early part of the novel that Mr Melmotte appears to have started life as a German; that he has spent some time in the United States, and in prison; that Mrs Melmotte is not his first wife, nor Marie Melmotte his legal daughter.

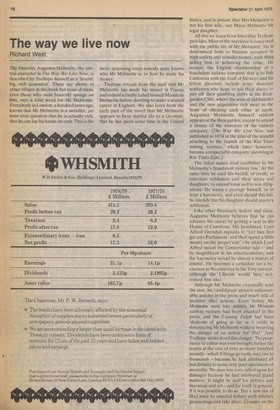

All this we learn from hints that Trollope provides. Most of the narrative is concerned with the public life of Mr Melmotte. He is determined both to become accepted in high society and to make money, each thing aiding him in achieving the other. He accepts the English chairmanship of a fraudulent railway company that is to link California with the Gulf of Mexico; and his fellow directors include some dissolute noblemen who hope to use their shares to pay off their gambling debts at the B eargarden Club, where the sons of old families and the new acquisitive rich meet in the hope of cheating each other at cards. Augustus Melmotte himself seldom appears at the Beargarden, except to attend a dinner of the directors of the railway company. (The Way We Live Now was published in 1874 at the time of the scandal attaching to the launch of the Rio Tinto mining venture, which later, however, became a respectable company, surviving as Rio Tinto-Zinc.) The titled names lend credibility to Mr Melmotte's fraudulent railway line. At the same time he used his wealth, or credit, to entertain noblemen and their wives and daughters, to extend loans and to win obligations. He wants a peerage himself, or at least a baronetcy. and even should this fail, he intends that his daughter should marry a nobleman.

Like other financiers, before and since, Augustus Melmotte believes that he can advance his career by getting a seat in the House of Commons. His henchman, Lord Alfred Grendall explains it: 'Let him first get into Parliament, and -then spend a little money on the proper side' — by which Lord Alfred meant the Conservative side — 'and be magnificent in his entertainments, and the baronetcy would be almost a matter of course'. He becomes a candidate for a byelection in Westminster in the Tory interest, although the Liberals would have welcomed him also.

Although Mr Melmotte eventually wins the seat, his candidature attracts unfavourable articles in the press and much talk of punitive libel actions. Even before Mr Melmotte went into politics, his Mexican railway venture had been attacked in the press, and the Evening Pulpit had been 'desirous of going as far as it could in denouncing Mr Melmotte without incurring the danger of an action for libel.' And Trollope understood this danger: 'No proprietor or editor was ever brought before the courts at the cost of ever so many hundred pounds —which if things go badly may rise to thousands — because he had attributed all but divinity to some very poor specimens of mortality. No man was ever called upon for damages because he had attributed grand motives. It might be well for politics and literature and art — and for truth in general, if it was possible to do so. But a new law of libel must be enacted before such salutary proceedings can take place. Censure on the Other hand is open to very grave perils.' No attacks on Mr Melmotte come from the pen of the authoress Lady Carbury, who is the another villain of The Way We Live Now. She is a woman of 43, a famous beauty, who once was married to a much Older man who beat her and accused her of infidelity. Now a widow, with two grown-up Children, Lady Carbury begins a career as a writer of popular history books. At the start of The Way We Live Now she has just completed Criminal Queens, the story of Semiramis, Cleopatra and Mary Queen of Scots, of whom Lady Carbury disapproves: Guilty! guilty always! Adultery Murder Treason and all the rest of it.'

Lady Carbury may not be a good historian but she is expert in what used to be called puffery, and now is called public relations. Trollope begins The Way We Live Now by reproducing the letters that Lady Carbury writes, in puffing her book, to Nicholas Broune, the editor of the Morning Breakfast Table, to Ferdinand Alf, the editor of the afore-mentioned Evening Pull*, and to Mr Booker, a critic of the Literary Chronicle.

Her approach is different to each of the three journalists. She has flirted with Mr Broune, 'the susceptible old goose'; has even allowed him to kiss her although, as Trollope makes clear, she has no physical interest in men. Her letter to Mr Alf, who earns £6,000 a year (equivalent to £90,000 after tax in modern money) is unsuccessful, for Criminal Queens is damned by the Even mg Pulpit. 'Poor Booker', as he is called in another of Trollope's novels, The Prime Minister, arranges a good review of Lady Carbury's book in return for a good review of his own latest book New Tales of a Tub in the Breakfast Table. He manages to review Criminal Queens in friendly fashion even 'Without cutting the book, so that its value for purposes of after sale might not be injured'. Trollope was here indulging in malice against the literary editor of the Spectator, on which the Literary Chronicle was modelled. The modern Lady Carbury would not of course be trying to puff her work on literary editors; she would be getting her face on television book programmes.

Lady Carbury, in The Way We Live Now, turns down an offer of marriage from Mr Etroune, even although the income of £3,000 a year would pay off her debts. All her hopes of financial stability rest on her son, Sir Felix Carbury, getting married to Marie Melmotte. And Marie actually loves the spoilt, heartless, evil baronet. She loves him although he has been bribed by Augustus Melmotte to lay off the suit; although he is dallying with a country girl, from Suffolk; although he considers her 'an infernal little ass' Augustus Melmotte has set aside money for Marie, not from affection but as a security against financial collapse. The prospect of this money encourages Sir Felix to Propose an elopement to Marie; after all, another 'city chap', Mr Goldsheiner, eloped with Lady Julia Start, and afterwards was forgiven, and now has a house close to Albert Gate.

Those were the days of women's emancipation, as ever brought across the Atlantic from the United States. Nowadays, a woman in California can sue her ex-lover for having abandoned her, spoilt her career and hurt her feelings. In The Way We Live Now the unlucky Paul Montagne not only becomes a director of Mr Melmotte's railway company but is pursued from California by the beautiful and strong-minded Winifred Hurtle who wants him to hold by his early promise of marriage. He has heard gossip about her, and some of the truth of this she admits. Yes, she did shoot a man dead in Oregon, but it is quite untrue to say that she fought a duel with her former husband. English men are so insipid, she thinks; how she would like to be introduced to the frank, ruthless Augustus Melmotte!

However, Augustus Melmotte gets his come-uppance. His fellow-director, the astute Mr Cohenlupe, makes off with the cash of the South Central Pacific and Mexican Railway. The Lord Mayor of London issues a warrant for the arrest of Mr Melmotte, who is now in the House of Commons. Mr Melmotte 'dines', in Trollope's phrase, on cognac mixed with champagne, and eight-inch-long cigars. He later rises to speak, is silent then slumps onto the back of the member in front of him. He goes home to his empty house and kills himself with a dose of prussic acid. This was, and is, as Trollope said, The Way We Live Now.

This is the last of three articles on Trollope's political England.

Previous page

Previous page