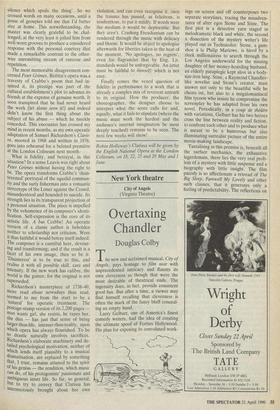

Music

Dangerous relationships

Robin Holloway

Iwill never forget Dr Leavis's master- classes in practical criticism. Occasional strangers were permitted to attend the thrice-weekly sessions in his cheerless room in Downing, but they were essential- ly devoted to the undergraduates of that college. Neither they nor the three assi- duous nuns ever opened their mouths, in spite of urgent invitation to collaborate. I had been advised by my tutor in King's (heartland of the Enemy) to make myself heard: 'There is a tendency to reverent silence which spoils the thing'. So we crossed words on many occasions, until a posse of groupies told me that I'd better stay at home. This notwithstanding, the master was clearly grateful to be .chal- lenged; at the very least it jolted him from well-worn grooves to produce a considered response with the personal courtesy that made a remarkable contrast to the other- wise unremitting stream of rancour . and repetition.

The most memorable disagreement con- cerned Peter Grimes. Britten's opera was a travesty of Crabbe's poem that had in- spired it, its prestige was part of the cultural establishment's plot to advance its friends at the expense of genuine worth. It soon transpired that he had never heard the work (let alone seen it!) and indeed didn't know the first thing about the subject of his abuse — which he meekly conceded. This encounter has crossed my mind in recent months, as my own operatic adaptation of Samuel Richardson's Claris- sa, mooted in 1968 and written in 1976, goes into rehearsal for a belated premiere at the London Coliseum next month.

What is fidelity, and betrayal, in this situation? In a sense Leavis was right about Peter Grimes without having the right to be. The opera transforms Crabbe's 'disin- terested' portrayal of the squalid commun- ity and the surly fisherman into a romantic stereotype of the Loner against the Crowd, misunderstood and hounded to suicide. Its strength lies in its transparent projection of a personal situation. The piece is impelled by the vehemence of its composer's identi- fication. Self-expression is the core of its artistic life. A bas Crabbe! An operatic version of a classic author is beholden neither to scholarship nor criticism. Were it thus faithful it would betray itself indeed. The composer is a cannibal here, devour- ing and transforming; and if the result is a facet of his own image, then so be it. `Disinterest' is to be true to this, and realise it with all possible skill, care and intensity. If the new work has calibre, the world is the gainer; for the original is not superseded.

Richardson's masterpiece of 1738-40, more read about nowadays than read, seemed to me from the start to be a `natural' for operatic treatment. The postage-stamp version of its 2,200 pages man wants girl, she resists, he rapes her, she dies — has just that sense of being larger-than-life, intenser-than-reality, upon which opera has always flourished. To be so drastic naturally involves sacrifices. Richardson's elaborate machinery and de- tailed psychological motivation, neither of which lends itself plausibly to a musical dramatisation, are replaced by something that, I trust, remains attuned to the spirit of his genius — the rendition, which music can do, of his protagonists' passionate and ambiguous inner life. So far, so general; but to try to convey that Clarissa has unconsciously brought about her own violation, and can even recognise it, once the trauma has passed, as felicitous, is tendentious, to put it mildly. If words were the medium it would be deplorable. But they aren't. Crashing Freudianism can be rendered through the music with delicacy and bloom. It would be abject to apologise afterwards for liberties taken in the heat of the moment. 'No apologies, no regrets', even for flagrancies that by Eng. Lit. standards would be unforgivable. An artist must be faithful to himself:• which is not easy.

Finally comes the vexed question of fidelity in performance to a work that is already a complex mix of reverent untruth to its original. How the producer, the choreographer, the designer choose to interpret what the score calls for and, equally, what it fails to stipulate (where the music must work the hardest and the audience's internal imagination be most deeply touched) remains to be seen. The next few weeks will show!

Robin Holloway's Clarissa will be given by the English National Opera at the London Coliseum, on 18, 22, 25 and 29 May and 1 June.

Previous page

Previous page