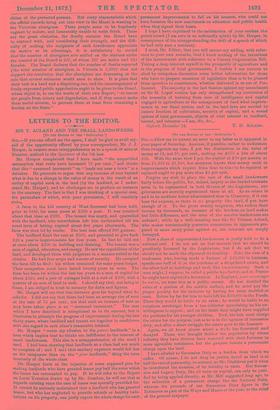

[TO THE EDITOR OF THE SPECTATOR."]

Sin,—Allow me to correct an error in my letter as it appeared in your paper of Saturday. Anxious, if possible, rather to understate than exaggerate my case, I put the diminution in the value of money at 15, not 25, per cent., making on £175 a loss of about £25. With the same view I put the capital of £50 per annum at from £1,000 to £1,500, but everyone knows that money sunk in improvements which require from time to time to be repaired or replaced ought to pay more than £5 per cent.

Forgive my wish to place the case of the small landowners fairly before the public, for, indeed, largely as the landed interests seem to be represented in both Houses of the Legislature, our grievances are scarcely represented there at all. As an estate is said to be nowhere better administered than in Chancery, if it can bear the expense, so there is no property like land, if you have enough of it. To the great county magnates, who reckon their income by thousands, an increase of the burdens on land makes but little difference, and the cries of the smaller landowners are unheard ; while by a well-meaning man like Sir Thomas Acland, who makes unreasonably generous concessions to opponents pre- pared to score every point against us, our interests are simply betrayed.

Now a class of impoverished landowners is justly held to be a national evil. I do not ask on that account that we should be

peculiarly favoured by the Legislature, but I do ask that we should not be made the objects of its hostility. Take the case of a tradesman who, having made a fortune of £20,000 in business, spends one-half of it in the purchase of a dilapidated estate, and

the other half in buildings and such like improvements. Such a man might, I suppose, be called a public ben-sfaetor, and in France

he might have expected a decoration. In England, pour encourager les mitres, we treat him as a public enemy. He has doubled the value of a portion of the earth's surface, and he must pay the proper penalty for his rashness by having his rates doubled at once. Better by far for him to have left his £10,000 in the Funds. There they would be liable to no rates ; he would be liable to no vexatious surcharges from a tax-collector speculating on his un- willingness to appeal ; and on his death they might have supplied the portions for his younger children. Now, his heir must charge the estate for the purpose, just as he is in the agonies of succession duty, and after a short struggle the estate goes to the hammer.

Again, we all know places where a trade has flourished and decayed. Those who brought thither the population by whose

industry they have thriven have removed with their fortunes to more agreeable residences, but the paupers remain a permanent charge upon the land. I have alluded to Succession Duty as a burden from which we suffer. Of course, I do not deny its justice, taxed as land is at half the rate of personalty, on account, as Mr. Gladstone put it when he introduced the measure, of its liability to rates. But Succes- sion and Legacy Duty, like all taxes on capital, can only be justi- fied by being applied directly, as Mr. Mill suggested long ago, to the reduction of a permanent charge like the National Debt, whereas the proceeds of our Succession Duty figure m the Estimates as part of the Ways and Means of the year, to the relief of the general taxpayer. I have now, Sir, with your kind permission, pointed out where, in my humble opinion, the incidence of rates and taxes bears most unfairly on landowners, as in my former letter I have, I hope, established that it is a great error to apply without qualification the doctrine of " unearned increment" to land used purely for agricultural purposes. I can mention a parish in Somersetebire where the rents are now lower than they were in the early part of

Previous page

Previous page