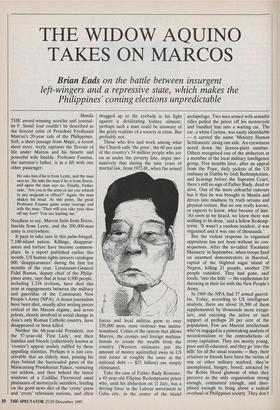

THE WIDOW AQUINO TAKES ON MARCOS

- Brian Eads on the battle between insurgent

left-wingers and a repressive state, which makes the Philippines' coming elections unpredictable

Manila THE award-winning novelist and journal- ist F. Sionil Jose couldn't be described as the fiercest critic of President Ferdinand Marcos's 20-year rule of the Philippines. Still, a short passage from Magic, a recent short story, wryly captures the flavour of life under Marcos and his bizarre and powerful wife Imelda. Professor Faustus, the narrator's father, is in a lift with one other passenger:

He asks him if he is from Leyte, and the man says no. He asks the man if he is from Ilocos, and again the man says no. Finally, Father asks, 'Are you in the army or are you related to any sergeant or officer?' Again, the man shakes his head. At this point, the great Professor Faustus gains some courage and tells the man, 'Then will you take your shoe off my foot? You are hurting me.'

Needless to say, Marcos hails from Ilocos, Imelda from Leyte, and the 200,000-man army is everywhere.

It pays to take care in this palm-fringed, 7,100-island nation. Killings, disappear- ances and torture have become common- place. In a report published earlier this month, US human rights lawyers catalogue 600 'disappearances' during the first ten months of the year. Lieutenant-General Fidel Ramos, deputy chief of the Philip- pines army, says that at least 4,500 people, including 1,334 civilians, have died this year in engagements between the military and guerrillas of the Communist New People's Army (NPA). A dozen journalists have been shot, usually after writing pieces critical of the Marcos regime, and seven priests, closely involved in social change in Asia's only Roman Catholic country, have disappeared or been killed.

Neither the 68-year-old President, nor the 57-year-old `First Lady', nor their families and friends (collectively known as `cronies') appear unduly ruffled by these appalling statistics. Perhaps it is just con- ceivable that an elderly man, passing his days behind the barricaded gates of the Malacanang Presidential Palace, venturing out seldom, and then behind the tinted windows of a Cadillac Fleetwood amid phalanxes of motorcycle outriders, feeding on the good news diet of the `crony' press and `crony' television stations, and often drugged up to the eyeballs in his fight against a debilitating kidney ailment; perhaps such a man could be unaware of the grisly realities of a society in crisis. But probably not.

Those who live and work among what the Church calls `the poor', the 60 per cent of the country's 54 million people who are on or under the poverty line, argue per- suasively that during the nine years of martial law, from 1972-81, when the armed forces and local militias grew to over 250,000 men, state violence was institu- tionalised. Critics of the system that allows Marcos, the cronies and foreign multina- tionals to cream the wealth from the country (Western estimates put the amount of money squirrelled away in US real estate at roughly the same as the national debt — $25 billion) are simply eliminated.

Take the case of Father Rudy Romano, a 45-year-old Filipino Redemptorist priest who, until his abduction on 11 July, was a driving force in the Labour movement in Cebu city, in the centre of the island archipelago. Two men armed with armalite rifles pulled the priest off his motorcycle and bundled him into a waiting car. The car, a white Cortina, was easily identifiable — it carried the name 'Ministry Human Settlements' along one side. An eyewitness noted down the licence-plate number. Others recognised one of the abductors as a member of the local military intelligence group. Five months later, after an appeal from the Pope, daily pickets of the US embassy in Dublin by Irish Redemptorists, and hearings before the Supreme Court, there's still no sign of Father Rudy, dead or alive. One of the more colourful rumours has it that he was brought to Manila and driven into madness by truth serums and physical torture. But no one really knows, or expects to know, what became of him. `As soon as we heard, we knew there was nothing to be done,' said a fellow Redemp- torist. 'It wasn't a random incident, it was organised and it was one of thousands.'

But the violent response to organised opposition has not been without its con- sequences. After the so-called Escalante Massacre' in September, when troops fired on unarmed demonstrators in Bacolod, capital of the blighted sugar island of Negros, killing 21 people, another 250 people vanished. They had gone, said locals, `into the hills' — the euphemism for throwing in their lot with the New People's Army.

In 1969 the NPA had 37 armed guerril- las. Today, according to US intelligence analysts, there are about 16,500 of them supplemented by thousands more irregu- lars, and enjoying the active or tacit support of perhaps 20 per cent of the population. Few are Marxist intellectuals who've engaged in a painstaking analysis of neocolonialism or the contradictions of crony capitalism. They are mostly young, poor and ill-educated, and they go 'into the hills' for all the usual reasons — they, their relatives or friends have been the victim of one or other military warlord, they're unemployed, hungry, bored, attracted by the Robin Hood glamour of what they perceive as the only organisation strong, enough, committed enough, and disci- plined enough to bring about a radical overhaul of Philippines society. They don't remain politically naïve for long. Each unit, which can range in size from a few dozen to a few hundred, has its political commissars to put flesh on the sloganising denunciations of the 'US-Marcos dicta- torship'. If the trend continues, say US analysts, the NPA will be strong enough to, fight the Philippines army to a stalemate within three years.

This, more than anything else, be it the wholesale misappropriation of military and economic aid, or the two-year tailspin of the Philippines' economy, is what has concentrated minds in Washington. It is why US officials carrying blunter and blunter messages, reaching a climax with Reagan's crony Senator Paul Laxalt in October, have beaten a path to the doors of Malacanang. It explains why on 3 November Marcos announced his 'snap' presidential election not in the national parliament, not on local radio and televi- sion, but in a live satellite interview with the US station ABC.

The President has always craved Amer- ican approval, and has usually got it. More important, he needs the arms aid and the syndicated multi-billion-dollar bank loans that will be given or withheld as Washing- ton sees fit. The United States needs its Subic Bay naval base, the biggest installa- tion outside America, and its Clark air- base. Both are seen as a forward defence against increasing Soviet activity in the Indian and Pacific oceans. It would cost an estimated six billion US dollars to relocate Subic, and any other Asian site, be it Saipan, Singapore or South Korea, would be third choice at best, impossible at worst. NPA guerrilla bands already prowl through the ill-maintained perimeter fences of Clark, and the spectre of another Saigon-style debacle is not a happy one. The United States needs either a Marcos with a cleaned-up act, or someone very like him, Enter Mrs Corazon (Cory) Aquino and Mr Salvador Laurel.

Mrs Aquino is the widow of former Senator Benigno Aquino — probably the only Filipino politician brave enough and ruthless enough to square up to Marcos. The result for him was seven years in jail, three years in exile, and a bullet in the brain even before his feet touched the tarmac of Manila airport in August 1983, Since her husband's assassination, the widow Aquino has attained the status of minor sainthood among many who oppose the Marcos dynasty. She agreed to contest the presidency if one million signatures were collected, and last week she regist- ered her candidacy. She entered her occupation as 'housewife'. `Doy' Laurel could not be described as an inhabitant of the moral high ground. His father was the Filipino President who collaborated with the Japanese during their wartime occupation of the country. He has been an intimate of Marcos, served as an assemblyman under Marcos's party, and kept mum until 1982 when he crossed over to the opposition. Unlike many old elite families, the Laurels didn't lose their lands and property during the martial law years, and the nicest thing anyone in Manila will say about `Doy' is that he is 'an arrogant, ambitious villain'. But things have not gone well for the Laurel clan in recent years. At his father's legendary parties the fountains ran with champagne. At `Doy's' 57th birth- day party last month the host ran out of liquor. He has, however, or claims to have, what Mrs Aquino and her backers do not — a nationwide political organisation, the United Nationalist Democratic Organisa- tion (Unido). After much will they, won't they drama, taking them to within one and a half hours of the registration deadline, he agreed to run as vice-presidential candi- date to Mrs Aquino, rather than go it alone for the presidency. They've been dubbed `the dream ticket'. Since Mrs Aquino's background is as privileged as Mr Laurel's one suspects it is the American dream.

Meanwhile, at the stately, chandeliered Manila hotel, the President was demon- strating that, if nothing else, he can choreograph a first-rate political extrava- ganza. The streets were thick with 'renta- crowd' supporters — 35 pesos (about £1.40) a head, plus a lunch of pork, boiled egg and rice. A huge airship, emblazoned with 'Marcos, now more than ever', ho- vered overhead. The President wore his `lucky shirt', a garish, rainbow-hued affair that first saw the light of day 20 years ago during his first campaign. Eight thousand, all-expenses-paid delegates acclaimed his candidacy, and in the cavernous hotel lobby the First Lady's entourage, the 'blue ladies', dressed confusingly in white, flut- tered between a regiment of security men.

The talk had been of a Draft Imelda campaign, with Mrs Marcos in the vice- presidential slot. 'She's the only one he can trust to protect the family interests after he's gone,' offered one diplomat. Instead he announced the name of Arturo Tolent- ino, a 75-year-old maverick dumped as foreign minister last March. With Arturo on the ticket, the opposition was inside the government. Why bother with the other squabbling, untested Aquino-Laurel opposition?

The Filipinos, whose 300 years under Spanish rule makes them seem like a people adrift from Latin America rather than at the heart of South-East Asia, are addicted to drama and spectacle. What is not certain is whether they will get the promised election next 7 February.

The Supreme Court has still to rule on 11 petitions charging that 'snap' elections are unconstitutional — there being no valid reason to bring them forward from the scheduled date in 1987. There is a pres- idential decree on the books that could be used to rule out the candidacy of anyone not continually resident in the Philippines for the past ten years. 'Cory' and `Doy' could be excluded.

If the election goes ahead, will it be a clean election? So far the only improve- ment on previous methods is the promise of transparent ballot boxes, and a handful of foreign observers. The President had no hesitation in reinstating his cousin and former chauffeur, General Fabian Ver, to the post of Chief of Staff of the armed forces after a hand-picked court found him and other defendants not guilty of involve- ment in the Aquino killing. The tradition of loyalty was more important than appeas- ing critics in Washington. Will he hesitate to manhandle himself back into power? Won't the Reagan administration, a la Lyndon Johnson, simply sigh: 'He might be a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch.'

And in the end, is it really relevant? The Left, from the armed struggle Left to the moderate nationalists, say not. 'Just the old elite politics,' said one young intellec- tual. 'They're moving back their US dollars to finance it and all it will mean for most people is another surge in inflation.' No wonder there's been a new T-shirt slogan on show of late — 'Yankee go home, and take me with you.'

`There's a special wallet for redundancy notices.'

Previous page

Previous page