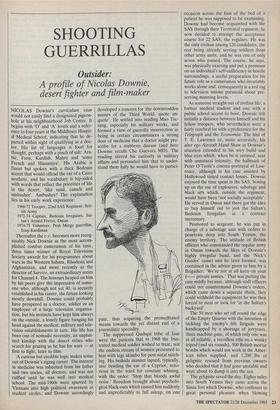

SHOOTING GUERRILLAS

Outsider: A profile of Nicolas Downie, desert fighter and film-maker

NICOLAS Downie's curriculum vitae would not easily find a designated pigeon- hole at his neighbourhood Job Centre. It begins with '0' and 'A' levels and a refer- ence to four years at the Middlesex Hospit- al Medical School, indicating that he de- parted within sight of qualifying as a doc- tor. His list of languages is food for thought, perhaps with a pinch of salt: Ara- bic, Farsi, Kurdish, Mahra and 'some French and Hassaniya'. His Arabic is fluent but spoken with a thick Bedouin accent that would offend the ear of a Cairo aesthete, and his vocabulary is lop-sided with words that reflect the priorities of life in the desert, 'like sand, camels and ambushes'. Ambushes? The explanation lies in his early work experience:

1968-72 Trooper, 22nd SAS Regiment, Brit- ish Army 1972-74 Captain, Bedouin Irregulars, Sul- tan's Armed Forces, Oman

1974-75 Volunteer, Pesh Merga guerrillas, Iraqi Kurdistan Thereafter the c. v. becomes more recog- nisably Nick Downie as the most accom- plished combat cameraman of his time, three times winner of Royal Television Society awards for his programmes about wars in the Western Sahara, Rhodesia and Afghanistan, and more recently as the director of Survive, an extraordinary series for Channel 4. The honours heaped on him by his peers give the impression of some- one who, although not yet 40, is securely established in his career, the future looking mostly downhill. Downie could probably have prospered as a doctor, soldier or an employee of a large television organisa- tion, but his instincts have kept him always on the outside, a lonely figure banging his head against the medical, military and tele- vision establishments in turn. His life has been one of nomadic necessity, an unplan- ned kinship with the desert tribes who search for grazing as he has for wars — at first to fight, later to film.

A curious but credible logic makes sense out of Downie's zigzag career. The interest in medicine was inherited from his father and two uncles, all doctors, and was not ruffled until he was well into medical school. The mid-1960s were spurred by Vietnam into high political awareness in student circles, and Downie accordingly developed a concern for 'the downtrodden masses of the Third World, quote un- quote'. He settled into reading Mao Tse- tung, especially his military works, and formed a view of guerrilla insurrection as being in certain circumstances a strong dose of medicine that a doctor might pre- scribe for a stubborn disease (and here Downie recalls Che Guevara MD). The reading stirred his curiosity in military affairs and persuaded him that to under- stand them fully he would have to partici- pate, thus acquiring the premeditated means towards the yet distant end of a journalistic speciality. The suppressed Qashqai tribe of Iran were the patients that in 1968 the frus- trated medical soldier wished to treat, not the endless stream of women presented to him with legs akimbo for post-natal stitch- ing. His bedside manner lapsed, typically, into bending the ear of a Cypriot, noto- rious in the ward for constant whining, with the order: 'Stop that bloody awful noise.' Boredom brought about psycholo- gical black-outs which caused him suddenly and unpredictably to fall asleep, on one occasion across the foot of the bed of a patient he was supposed to be examining.

Downie had become acquainted with the SAS through their Territorial regiment; he now decided to attempt the acceptance course for 22 SAS, the regulars. He was the only civilian among 120 candidates, the rest being already serving soldiers from other army units, and he was one of only seven who passed. The course, he says, was physically exacting and put a premium on an individual's self-sufficiency in hostile surroundings, a useful preparation for his future role as a cameraman who invariably works alone and, consequently is a red rag to television unions paranoid about pre- serving manning levels.

As someone straight out of civilian life, a former medical student and one with a public school accent to boot, Downie felt initially a distance between himself and his fellow troopers, who nevertheless were a fairly cerebral lot with a preference for the Telegraph and the Economist. The hint of T. E. Lawrence or, more accurately, his alter ego Aircraft Hand Shaw in Downie's situation extended to his wiry build and blue eyes which, when he is aroused, sear with unnatural intensity, the hallmark of Peter O'Toole's cinema portrayal of Law- rence, although in his case assisted by Hollywood tinted contact lenses. Downie enjoyed the time spent in the SAS, boning up on the use of explosives, sabotage and black arts which, outside the regiment, would have been 'not socially acceptable'. He served in Oman and there got the idea to buy himself out to join the Sultan's Bedouin Irregulars as a contract mercenary.

Promoted to sergeant, he was put in charge of a sabotage unit with orders to penetrate deep into South Yemen, the enemy territory. The attitude of British officers who commanded the regular army in Oman towards the likes of Downie's highly irregular band, and the 'Nick's Guides' camel unit he later formed, was contained in the advice given to him by a Brigadier: 'We're not at all keen on your f— private armies.' That was putting the case mildly because, although staff officers could not countermand Downie's orders, which came down a separate chain, they could withhold the equipment he was then forced to steal or look for 'in the Sultan's backyard'.

The 50 men who set off round the edge of the Empty Quarter with the intention of tackling the enemy's 6th Brigade were handicapped by a shortage of jerrycans, three machine guns, of which only one was at all reliable, a recoilless rifle on a wonky tripod (and six rounds), 500 British mortar bombs which would not work in the Amer- ican tubes supplied, and 1,200 lbs of gelignite rescued from previous owners who decided that it had gone unstable and were about to dump it into the sea.

The gelignite saved the day. Eighty miles into South Yemen they came across the Sinau fort which Downie, who confesses to great personal pleasure when blowing things up, decided to eliminate 'as a prelude to operations and as a demonstra- tion that we had arrived'. His calculations showed the need for 300 lbs of gelignite so he laid 1,000 lbs. 'Always multiply by the P-factor,' is his motto in such circumst- ances, `P for Plenty.' The occupants were invited to surrender, which they did. A quick search of the premises uncovered a vast quantity of tinned green beans, which thereupon become the staple diet of Dow- nie's unit for the rest of the operation. The fuse was ignited with Downie's Land- Rover, nearly 100,000 miles on the clock, standing by with its engine running. 'The P-factor turned the whole thing to dust the fort, a government shop, the garage, and some guy's house at the back. It was one of the great achievements of my life.' Now in excellent spirits, he chose to ask questions before opening fire on what looked like an enemy patrol attracted by the fuss. They turned out to be Yemeni rebels who had been combing the desert hoping to join up with Downie's team. There were led by a former law student in London, once a neighbour of Downie's in Gloucester Road. 'Charming fellow,' Downie recalls. 'We hadn't actually met before. I had already put jets on standby to deal with him when he walked up and said: "Hello, my name's Ahmed. What's yours?" ' The demolition of the fort and the subsequent success of Downie's camel unit delighted the Sultan into writing out a £500,000 cheque for re-equipment and expansion. The emissary sent to London with the cheque and a shopping list made the mistake of adopting a false name when placing his exotic order with a shop in Piccadilly. The suspicious proprietor, assuming he had the IRA in his shop, patriotically had the premises invaded by the Special Branch instead of proceeding with the transaction. The disgusted shop- per decided that he had had enough of irregular warfare in Oman and never went back, although the cheque did. He was soon rejoined in London by an equally disgusted Downie, disillusioned by the undermining of his best efforts by the British officer corps. His ultimate vindica- tion in Oman came about when his furgha, the only group of irregulars who had not previously mutinied, did then mutiny with the express purpose of having him brought back to continue leading them.

Downie's final stint as a fighter was with the Pesh Merga guerrillas in Iraqi Kurdis- tan, whom he joined after driving out from London in a Renault 4. The operation for which he trained a group of saboteurs would have overshadowed his initiation on the Sinau fort as it involved the devastation of Baghdad. The details he is reserving for a book he intends to write. Baghdad was spared what he had cooked up for it by a sudden change in major-power politics affecting the war. The affair might have made good television because the back of the Renault 4 contained two items which had not previously been part of Downie's portable kit, a 16mm film camera and a slim volume entitled Hints on Movie- Making.

The expedition produced a clip of film lasting 40 seconds for which the BBC paid him £60. It was, frame for frame, more money than he has since been able to winkle out of the television industry, espe- cially the BBC. An industry which luxuri- ates in bloated manning agreements, first- class travel, compulsory rest breaks and unfathomable overtime payments' has nev- er been receptive to the solitary figure who drives to war in a Renault 4, adopts native dress when necessary to minimise the danger of making the camera's presence more important than the events it is in- tended to record, and works with only as much equipment as he can carry on his own back. He has suffered more strain in the struggle to get his programmes cleared for transmission and to recover his costs (he is forced to re-mortgage his house for work- ing capital) than from anything that hap- pens on the battlefield. He does not wallow `Seat belt, Number Three!' in self-pity but does regret the effect of constant financial uncertainty on his wife, Hilary, and their three children. He is sad, too, about the number of friends and colleagues who have been killed in his company, mostly anonymous guerrillas, but also Lord Richard Cecil, who was shot in Rhodesia.

Thames Television have been Downie's most loyal patron, almost always battling against the ACTT shop stewards. The most deplorable controversy arose over his award-winning film on Afghanistan. A strike was called in London over a domes- tic dispute while Downie was filming deep inside Afghanistan in what were, even by his exalted standards, very dangerous con- ditions. He emerged, having covered hun- dreds of miles on foot, to be received as a pariah by the union, which he had recently joined, because he had not heard about the strike and immediately downed tools. His union card bore an endorsement that made his membership conditional on 'hazard assignment' and invalid at other times. His programme on the Vietnamese 'boat peo- ple' is locked in a vault and has never been seen, not even by himself, because the union could not agree that it was hazardous enough.

Downie habitually commits the heresy of writing and delivering the commentary for the films he has shot — nobody is pre- sumed to have the brains to do all three and gets into extra trouble for it One group of Afghan guerrillas were so enraged by his uncomplimentary assessment of their military prowess that they put a price on his head. His criticism of Robert Mugabe's Zanla guerrillas is a mixture of contempt and pity — 'the pits,' he recalls, `far too many of them lying on the ground waiting to be shot like turkeys.' Such comments have led to accusations of rac- ism, but his friends dismiss them. 'There isn't a chromosome of racism in his make- up,' one says. 'His judgment in these matters is purely military.' As far as Downie's political views can be divined, he seems to believe that no single ideological strait-jacket is universally applicable and that different problems call for different solutions.

Although some Afghans are not pleased with Downie, the Polisario guerrillas in the Sahara have spun around him a legend with distinct Lawrentian tones. His excep- tional toughness and composure under fire — a snatch of film records the moment when a guerrilla a few yards away has his head blown off — led to speculation about his true identity. He did not entirely conceal his SAS background, but it was in any case meaningless in the desert as it would have been to most people in Britain before the publicity of the regiment's storming of the Iranian embassy. Journal- ists who long afterwards followed Dow- nie's tracks among the Polisario took some time to put a name to the facts about a mysterious figure, the hero of tales related with awe by guerrillas and known to them simply as 'The Englishman'.

Previous page

Previous page