Gardens

Parasites with personality

Ursula Buchan

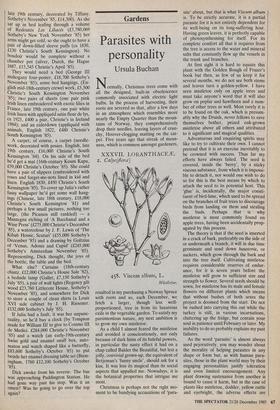

ormally, Christmas trees come with all the designed, built-in obsolescence commonly associated with electric light bulbs. In the process of harvesting, their roots are severed so that, after a few days in an atmosphere which resembles more nearly the Empty Quarter than the moun- tains of Norway, they comprehensively drop their needles, leaving layers of crun- chy, Hoover-clogging matting on the car- pet. Five years ago that streak of mean- ness, which is common amongst gardeners, XXXVII. LORANTHACEJE 2. CalyciJiora?] 458. Viscum album, L.

Mistletoe.

resulted in my purchasing a Norway Spruce with roots and so, each December, we fetch a larger, though less well- proportioned, tree in from its luxurious exile in the vegetable garden. To satisfy my parsimonious nature, my next ambition is to grow my own mistletoe.

As a child I almost feared the mistletoe and avoided it conscientiously, not only because of dark hints of its baleful powers, in particular the nasty effect it had on a chap called Balder the Beautiful, but lest a jolly, convivial grown-up, the equivalent of Betjeman's 'funny uncle', should ask for a kiss. It was less its magical than its social aspects that appalled me. Nowadays, it is the botanical properties that intrigue me most.

Christmas is perhaps not the right mo- ment to be bandying accusations of 'para- site' about, but that is what Viscum album is. To be strictly accurate, it is a partial parasite for it is not entirely dependent for its well-being on its long-suffering host. Having green leaves, it is perfectly capable of photosynthesising for itself. For its complete comfort all that it requires from the tree is access to the water and mineral salts that constantly flow up the vessels in the trunk and branches.

At first sight it is hard to equate this plant with the Golden Bough of Frazer's book but then, as few of us keep it for several months, we do not see both stems and leaves turn a golden-yellow. I have seen mistletoe only on apple trees and must take anyone's word that it will also grow on poplar and hawthorn and a num- ber of other trees as well. Most rarely it is to be found on the oak, which is presum- ably why the Druids, never fellows to save themselves bother, prized oak-grown mistletoe above all others and attributed to it significant and magical qualities.

Adventurous and enquiring spirits may like to try to cultivate their own. I cannot pretend that it is an exercise inevitably to be crowned with success. Thus far my efforts have always failed. The seed is covered, inside the 'berry', by a sticky viscous substance, from which it is impossi- ble to detach it, nor would one wish to do so for this is the best means by which to attach the seed to its potential host. This `glue' is, incidentally, the major consti- tuent of bird-lime, which used to be spread on the branches of fruit trees to discourage birds from landing on them and stealing the buds. Perhaps that is why mistletoe is most commonly found on apple trees, having been accidentally prop- agated by this process.

The theory is that if the seed is inserted in a crack of bark, preferably on the side of or underneath a branch, it will in due time germinate and send down haustoria, or suckers, which grow through the bark and into the tree itself. Cultivating mistletoe requires considerable reserves of endur- ance, for it is seven years before the mistletoe will grow to sufficient size and strength to flower. Several seeds should be sown, for mistletoe has its male and female flowers on different plants which means that without bushes of both sexes the project is doomed from the start. Do not be rushed into carrying this out while the turkey is still, in various incarnations, cluttering up the fridge, but contain your soul in patience until February or later. My inability to do so probably explains my past failures.

As the word 'parasite' is almost always used pejoratively, you may wonder about the morality of helping parasites in any shape or form but, as with human para- sites, those in the plant world may by their engaging personalities justify toleration and even limited encouragement. Any plant drawing sustenance from another is bound to cause it harm, but in the case of plants like mistletoe, dodder, yellow rattle and eyebright, the adverse effects are negligible. Occasionally their virtue is such that they are cultivated as ornamental garden plants. That is true of the toothwort called Lathraea clandestina, a root para- site, which is sometimes to be found in botanical gardens poking up its fine purple heads of flowers a few feet away from a large poplar or willow.

Parasites have eked out an existence in every age and every clime but in the tropical jungle, where light and sunshine are lacking, they positively luxuriate. Raf- flesia arnoldii, whose dark red flower weighs 15 pounds and measures a yard across, is completely dependent on a tro- pical vine called Cissus angustifolia. It was first discovered by Sir Stamford Raffles, when he walked across the interior of Sumatra, early in the 19th century. Some- how, however, I cannot imagine that the founder of Singapore would be flattered by the thought that, in gardening circles, his name would be remembered not for the creation of a colony, nor even for a luxury hotel, but for the largest and smelliest parasite in the world.

Intriguing, if hardly beautiful, is the Great Broomrape which palely loiters in ever-diminishing quantities on heathland. Like many parasites, it is sickly-looking and also rare. Living off its neighbours, in this case broom and gorse, does not seem to result in a healthy and vigorous exist- ence. Perhaps there is a moral lesson to be drawn here after all; something along the lines of the error of sponging off one's friends.

Previous page

Previous page