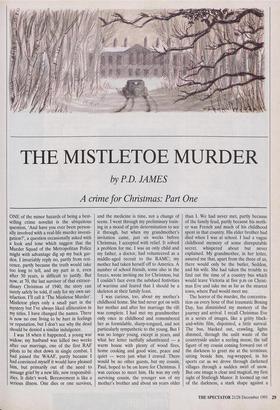

THE MISTLETOE MURDER

by PD. JAMES A crime for Christmas: Part One

ONE of the minor hazards of being a best- selling crime novelist is the ubiquitous question, 'And have you ever been person- ally involved with a real-life murder investi- gation?', a question occasionally asked with a look and tone which suggest that the Murder Squad of the Metropolitan Police might with advantage dig up my back gar- den. I invariably reply no, partly from reti- cence, partly because the truth would take too long to tell, and my part in it, even after 50 years, is difficult to justify. But now, at 70, the last survivor of that extraor- dinary Christmas of 1940, the story can surely safely be told, if only for my own sat- isfaction. I'll call it 'The Mistletoe Murder'. Mistletoe plays only a small part in the mystery but I've always liked alliteration in my titles. I have changed the names. There is now no one living to be hurt in feelings or reputation, but I don't see why the dead should be denied a similar indulgence.

I was 18 when it happened, a young war widow; my husband was killed two weeks after our marriage, one of the first RAF pilots to be shot down in single combat. I had joined the WAAF, partly because I had convinced myself it would have pleased him, but primarily out of the need to assuage grief by a new life, new responsibil- ities. It didn't work. Bereavement is like a serious illness. One dies or one survives, and the medicine is time, not a change of scene. I went through my preliminary train- ing in a mood of grim determination to see it through, but when my grandmother's invitation came, just six weeks before Christmas, I accepted with relief. It solved a problem for me. I was an only child and my father, a doctor, had volunteered as a middle-aged recruit to the RAMC; my mother had taken herself off to America. A number of school friends, some also in the forces, wrote inviting me for Christmas, but I couldn't face even the subdued festivities of wartime and feared that I should be a skeleton at their family feast.

I was curious, too, about my mother's childhood home. She had never got on with her mother and after her marriage the rift was complete. I had met my grandmother only once in childhood and remembered her as formidable, sharp-tongued, and not particularly sympathetic to the young. But I was no longer young, except in years, and what her letter tactfully adumbrated — a warm house with plenty of wood fires, home cooking and good wine, peace and quiet — were just what I craved. There would be no other guests, but my cousin, Paul, hoped to be on leave for Christmas. I was curious to meet him. He was my only surviving cousin, the younger son of my mother's brother and about six years older than I. We had never met, partly because of the family feud, partly because his moth- er was French and much of his childhood spent in that country. His elder brother had died when I was at school. I had a vague childhood memory of some disreputable secret, whispered about but never explained. My grandmother, in her letter, assured me that, apart from the three of us, there would only be the butler, Seddon, and his wife. She had taken the trouble to find out the time of a country bus which would leave Victoria at five p.m on Christ- mas Eve and take me as far as the nearest town, where Paul would meet me.

The horror of the murder, the concentra- tion on every hour of that traumatic Boxing Day, has diminished my memory of the journey and arrival. I recall Christmas Eve in a series of images, like a gritty black- and-white film, disjointed, a little surreal. The bus, blacked out, crawling, lights dimmed, through the unlit waste of the countryside under a reeling moon; the tall figure of my cousin coming forward out of the darkness to greet me at the terminus; sitting beside him, rug-wrapped, in his sports car as we drove through darkened villages through a sudden swirl of snow. But one image is clear and magical, my first sight of Stutleigh Manor. It loomed up out of the darkness, a stark shape against a grey sky pierced with a few high stars. And then the moon moved from behind a cloud and the house was revealed; beauty, sym- metry and mystery bathed in white light.

Five minutes later I followed the small circle of light from Paul's torch through the porch with its country paraphernalia of walking-sticks, brogues, rubber boots and umbrellas, under the black-out curtain and into the warmth and brightness of the square hall. I remember the huge log fire in the hearth, the family portraits, the air of shabby comfort, and the mixed bunches of holly and mistletoe above the pictures and doors, which were the only Christmas decoration. My grandmother came slowly down the wide wooden stairs to greet me, smaller than I had remembered, delicately boned and slightly shorter even than my five-foot-three. But her handshake was sur- prisingly firm and, looking into the sharp, intelligent eyes, at the set of the obstinate mouth, so like my mother's, I knew that she was still formidable.

I was glad I had come, glad to meet for the first time my only cousin, but my grand- mother had in one respect misled me. There was to be a second guest, a distant relation of the family, who had driven from London earlier and arrived before me. I met Rowland Maybrick for the first time when we gathered for drinks before dinner in a sitting-room to the left of the main hall. I disliked him on sight and was grate- ful to my grandmother for not having sug- gested that he should drive me from London. The crass insensitivity of his greet- ing — 'You didn't tell me, Paul, that I was to meet a pretty young widow' — rein- forced my initial prejudice against what, with the intolerance of youth, I thought of as a type. He was in the uniform of a flight- lieutenant but without wings — Wingless Wonders, we used to describe them darkly handsome, full-mouthed under the thin moustache, his eyes amused and spec- ulative, a man who fancied his chances. had met his type before and hadn't expect- ed to encounter it at the Manor. I learned that in civilian life he was an antique deal- er. Paul, perhaps sensing my disappoint- ment at finding that I wasn't the only guest, explained that the family needed to sell some valuable coins. Rowland, who spe- cialised in coinage, was to sort and price them with a view to finding a purchaser. And he wasn't only interested in coins. His gaze ranged over furniture, pictures, porce- lain and bronze, his long fingers touched and caressed as if he were mentally pricing them for sale. I suspected that, given half a chance, he would have pawed me and assessed my second-hand value.

My grandmother's butler and cook, Indispensable small-part characters in any country house murder, were respectful and competent but deficient in seasonal good- will. My grandmother, if she gave the mat- ter thought, would probably have described them as faithful and devoted retainers, but I had my doubts. Even in 1940 things were changing. Mrs Seddon seemed to be both overworked and bored, a depressing com- bination, while her husband barely con- tained the lugubrious resentment of a man calculating how much more he could have earned as a war-worker at the nearest RAF base.

I liked my room; the four-poster with its faded curtains, the comfortable low chair beside the fire, the elegant little writing- desk, the prints and watercolours, fly-blown in their original frames. Before getting into bed I put out the bedside light and drew aside the black-out curtain. High stars and moonlight, a dangerous sky. But this was Christmas Eve. Surely they wouldn't fly tonight. And I thought of women all over Europe drawing aside their curtains and looking up in hope and fear at the menac- ing moon.

I woke early next morning, missing the jangle of Christmas bells, bells which in

1940 would have heralded invasion. Next day the police were to take me through every minute of that Christmas, and every detail remains clearly in memory 52 years later.

After breakfast we exchanged presents. My grandmother had obviously raided her jewel-chest for her gift to me of a charming enamel and gold brooch, and I suspect that Paul's offering, a Victorian ring, a garnet surrounded with seed pearls, came from the same source. I had come prepared. I parted with two of my personal treasures in the cause of family reconciliation, a first edition of A Shropshire Lad for Paul and an early edition of Diary of a Nobody for my grandmother. They were well received. Rowland's contribution to the Christmas rations was three bottles of gin, packets of tea, coffee and sugar, and a pound of but- ter, probably filched from RAF stores. Just before mid-day the depleted local church choir arrived, sang half a dozen unaccom- panied carols embarrassingly out of tune, were grudgingly rewarded by Mrs Seddon with mulled wine and mince-pies and, with obvious relief, slipped out again through the black-out curtains to their Christmas dinners.

After a traditional meal served at one

o'clock, Paul asked me to go for a walk. I wasn't sure why he wanted my company. He was almost silent as we tramped doggedly over the frozen furrows of deso- late fields and through birdless copses as joylessly as if on a route march. The snow had stopped falling but a thin crust lay crisp and white under a gunmetal sky. As the light faded, we returned home and saw the back of the blacked-out manor, a grey L-shape against the whiteness. Suddenly, with an unexpected change of mood, Paul began scooping up the snow. No one receiving the icy slap of a snowball in the face can resist retaliation, and we spent 20 minutes or so like school-children, laughing and hurling snow at each other and at the house, until the snow on the lawn and grav- el path had been churned into slush.

The evening was spent in desultory talk in the sitting-room, in dozing and reading. The supper was light, soup and herb omelettes — a welcome contrast to the heaviness of the goose and Christmas pud- ding — served very early, as was the cus- tom, so that the Seddons could get away to spend the night with friends in the village. After dinner we moved again to the ground-floor sitting-room. Rowland put on the gramophone, then suddenly seized my hands and said, 'Let's dance.' The gramo- phone was the kind that automatically played a series of records and as one popu- lar disc dropped after another — `Jeepers Creepers', 'Beer Barrel Polka', 'Tiger Rag', `Deep Purple' — we waltzed, tangoed, fox- trotted, quick-stepped round the sitting- room and out into the hall. Rowland was a superb dancer. I hadn't danced since Alas- tair's death but now, caught up in the exu- berance of movement and rhythm, I forgot my antagonism and concentrated on fol- lowing his increasingly complicated lead, The spell was broken when, breaking into a waltz across the hall and tightening his grasp, he said:

`Our young hero seems a little subdued. Perhaps he's having second thoughts about this job he's volunteered for.'

`What job?'

`Can't you guess? French mother, Sor- bonne educated, speaks French like a native, knows the country. He's a natural.'

I didn't reply. I wondered how he knew, if he had a right to know. He went on: `There comes a moment when these gal- lant chaps realise that it isn't play-acting any more. From now on it's for real. Enemy territory beneath you, not dear old Blighty; real Germans, real knives, real tor- ture-chambers and real pain.'

I thought: And real death, and slipped out of his arms hearing, as I re-entered the sitting-room, his low laugh at my back.

Shortly before ten o'clock my grand- mother went up to bed, telling Rowland that she would get the coins out of the study safe and leave them with him. He was due to drive back to London the next day; it would be helpful if he could examine them tonight. He sprang up at once and they left the room _together. Her final words to Paul were: `There's an Edgar Wallace play on the Home Service which I may listen to. It ends at 11. Come to say goodnight then, if you will, Paul, Don't leave it any later.'

As soon as they'd left, Paul said: 'Let's have the music of the enemy', and replaced the dance records with Wagner. As I read, he got out a pack of cards from the small desk and played a game of patience, scoptl- ing at the cards with furious concentration while the Wagner, much too loud, beat against my ears. When the carriage-clOck on the mantelpiece struck 11, heard in a lull in the music, he swept the cards togeth- er and said: `Time to say goodnight to Grandmama. Is there anything you want?

`No,' I said, a little surprised. 'Nothing.'

What I did want was the music a little less loud and when he left the room I turned it down. He was back very quickly. When the police questioned me next day, I told them that I estimated that he was away for about three minutes. It certainly couldn't have been longer. He said calmly: `Grandmama wants to see you.'

We left the sitting-room together and crossed the hall. It was then that my senses, preternaturally acute, noticed two facts. One I told the police; the other I didn't. Six mistletoe berries had dropped from the mixed bunch of mistletoe and holly fixed to the lintel above the library door and lay like scattered pearls on the polished floor. And at the foot of the stairs there was a small puddle of water. Seeing my glance, Paul took out his handkerchief and mopped it up. He said: `I should be able to take a drink up to Grandmama without spilling it.'

She was propped up in bed under the canopy of the four-poster, looking dimin- ished, no longer formidable, but a tired, very old woman. I saw with pleasure that she had been reading the book I'd given her. It lay open on the round bedside table beside the table-lamp, her wireless, the ele- gant little clock, the small half-full carafe of water with a glass resting over its rim, and a porcelain model of a hand rising from a frilled cuff on which she had placed her rings. She held out her hand to me; the fin- gers were limp, the hand cold and listless, the grasp very different from the firm handshake with which she had first greeted me. She said: `Just to say goodnight, my dear, and thank you for coming. In wartime, family feuds are an indulgence we can no longer afford.'

On impulse I bent down and kissed her forehead. It was moist under my lips. The gesture was a mistake. Whatever it was she wanted from me, it wasn't affection.

We returned to the sitting-room. Paul asked me if I drank whisky When I said that I disliked it, he fetched from the drinks cupboard a bottle for himself and a decanter of claret, then took up the pack of cards again, and suggested that he should teach me poker. So that was how I spent Christmas night from about 11.10 until nearly two in the morning, playing endless games of cards, listening to Wagner and Beethoven, hearing the crackle and hiss of burning logs as I kept up the fire, watching my cousin drink steadily until the whisky bottle was empty. In the end I accepted a glass of claret. It seemed both churlish and censorious to let him drink alone. The car- riage-clock struck 1.45 before he roused himself and said: `Sorry, cousin. Rather drun.k. Be glad of your shoulder. To bed, to sleep, perchance to dream.'

We made slow progress up the stairs. I opened his door while he stood propped against the wall. The smell of whisky was only faint on his breath. Then with my help he staggered over to the bed, crashed down and was still.

At eight p'clock next morning Mrs Sed- don brought in my tray of early morning tea, switched on the electric fire and went quietly out with an expressionless, 'Good morning, madam.' Half awake, I reached over to pour the first cup when there was a hurried knock, the door opened, and Paul entered. He was already dressed and, to my surprise, showed no signs of a hangover. He said: `You haven't seen Maybrick this morn- ing, have you?'

`I've only just woken up.'

`Mrs Seddon told me his bed hadn't been slept in. I've just checked. He doesn't appear to be anywhere in the house. And the library door is locked.'

Some of his urgency conveyed itself to me. He held out my dressing-gown and I slipped into it and, after a second's thought, pushed my feet into my outdoor shoes, not my bedroom slippers. I said: `Where's the library key?'

`On the inside of the library door. We've only the one.'

The hall was dim, even when Paul switched on the light, and the fallen berries from the mistletoe over the study door still gleamed milk-white on the dark wooden floor. I tried the door and, leaning down, looked through the keyhole. Paul was right, the key was in the lock. He said: `We'll get in through the French win- dows. We may have to break the glass.'

We went out by a door in the north wing. The air stung my face. The night had been frosty and the thin covering of snow was still crisp except where Paul and I had frol- icked the previous day. Outside the library was a small patio about six feet in width leading to a gravel path bordering the lawn.

The double set of footprints was plain to see. Someone had entered the library by the French windows and then left by the same route. The footprints were large, a lit- tle amorphous, probably made, I thought, by a smooth-soled rubber boot, the first set partly overlaid by the second. Paul warned:

`Don't disturb the prints. We'll edge our way close to the wall.'

`The door in the French windows was closed but not locked. Paul, his back hard against the window, stretched out a hand to open it, slipped inside and drew aside first the black-out curtain and then the heavy brocade. I followed. The room was dark except for the single green-shaded lamp on the desk. I moved slowly towards it in fasci- nated disbelief, my heart thudding, hearing behind me a rasp as Paul violently swung back the two sets of curtains. The room was suddenly filled with a clear morning light annihilating the green glow, making horribly visible the thing sprawled over the desk.

He had been killed by a single blow of immense force which had crushed the top of his head. Both his arms were stretched out sideways, resting on the desk. His left shoulder sagged as if it, too, had been struck, and the hand was a spiked mess of splintered bone in a pulp of congealed blood. The face of his heavy gold wrist- watch had been smashed and tiny frag- ments of glass glittered on the desk top like diamonds. Some of the coins had rolled onto the carpet and the rest littered the desk, sent jangling and scattering by the force of the blows. Looking up, I checked that the key was indeed in the lock. Paul was peering at the smashed wrist-watch. He said; 'Half-past ten. Either he was killed then or we're meant to believe he was.'

There was a telephone beside the door and I waited, not moving, while he got through to the exchange and called the police. Then he unlocked the door and we went out together. He turned to re-lock it — it turned noiselessly as if recently oiled — and pocketed the key. It was then that noticed that we had squashed some of the fallen mistletoe berries into pulp.

***

Inspector George Blandy arrived within 30 minutes. He was a solidly built country- man, his straw-coloured hair so thick that it looked like thatch above the square, weath- er-mottled face. He spoke and moved with deliberation, whether from habit or because he was still recovering from an over-indulgent Christmas it was impossible. to say. He was followed soon afterwards by the Chief Constable himself. Paul had told me about him. Sir Rouse Armstrong was an ex-colonial governor, and one of the last of the old school of chief constables, obvi- ously past normal retiring age. He was very tall with the face of a meditative eagle; he greeted my grandmother by her Christian name and followed her upstairs to her pri- vate sitting-room with the grave conspirato- rial air of a man called in to advise on some urgent and faintly embarrassing family liminess. I had the feeling that Inspector Blandy was slightly intimidated by his pres- ence and I hadn't much doubt who would be effectively in charge of this investiga- tion.

I expect you are thinking that this is typi- cal Agatha Christie, and you are right: that's exactly how it struck me at the time. But one forgets, homicide rate excepted, how similar my mother's England was to Dame Agatha's Mayhem Parva. And it seems entirely appropriate that the body should have been discovered in the library, that most fatal room in popular British fic- tion.

The body couldn't be moved until the police surgeon arrived. He was at an ama- teur pantomime in the local town and it took some time to reach him. Dr Bywaters was a rotund, short, self-important little man, red-haired and red-faced, whose nat- ural irascibility would, I thought, have dete- riorated into active ill-humour if the crime had been less portentous than murder and the place less prestigious than the Manor.

Paul and I were tactfully excluded from the study while he made his examination. Grandmama had decided to remain upstairs in her sitting-room. The Seddons, fortified by the consciousness of an unas- sailable alibi, were occupied making and serving sandwiches and endless cups of cof- fee and tea, and seemed for the first time to be enjoying themselves. Rowland's Christmas offerings were coming in useful and, to do him justice, I think the knowl- edge would have amused him. Heavy foot- steps tramped backwards and forwards across the hall, cars arrived and departed, telephone calls were made. The police measured, conferred, photographed.

The body was eventually taken away shrouded on a stretcher and lifted into a sinister little black van while Paul and I watched from the sitting-room window. Our fingerprints had been taken, the police explained, to exclude them from any found on the desk. It was an odd sensation to have my fingers gently held and pressed onto what I remember as a kind of ink-pad. We were, of course, questioned, separately and together. I can remember sitting oppo- site Inspector Blandy, his large frame fill- ing one of the armchairs in the sitting- room, his heavy legs planted on the carpet, as conscientiously he went through every detail of Christmas Day. It was only then that I realised that I had spent almost every minute of it in the company of my cousin.

At 7.30 the police were still in the house. Paul invited the Chief Constable to dinner, but he declined, less, I thought, because of any reluctance to break bread with possible suspects than from a need to return to his grandchildren. Before leaving he paid a prolonged visit to my grandmother in her room, then returned to the sitting-room to report on the results of the day's activities. I wondered whether he would have been as forthcoming if the victim had been a farm labourer and the place the local pub.

He delivered his account with the stacca- to self-satisfaction of a man confident that he's done a good day's work.

`I'm not calling in the Yard. I did eight years ago when we had our last murder. Big mistake. All they did was upset the locals. The facts are plain enough. He was killed by a single blow delivered with great force from across the desk and while he was rising from the chair. Weapon, a heavy blunt instrument. The skull was crushed but there was little bleeding — well, you saw for yourselves. I'd say he was a tall murderer, Maybrick was over six foot two.

`We always have Christmas dinner with all the trimmings.' He came through the French windows and went out the same way. We can't get much from the footprints, too amorphous, but they're plain enough, the second set over- laying the first. Could have been a casual thief, perhaps a deserter, we've had one or two incidents lately. The blow could have been delivered with a rifle-butt. It would be about right for reach and weight. The library door to the garden may have been left open. Your grandmother told Seddon she'd see to the locking up but asked May- brick to check on the library before he went to bed. In the black-out the murderer wouldn't have known the library was occu- pied. Probably tried the door, went in, caught a gleam of the money and killed almost on impulse.'

Paul asked: 'Then why not steal the coins?'

`Saw that they weren't legal tender. Diffi- cult to get rid of. Or he might have pan- icked or thought he heard a noise.'

Paul asked: 'And the locked door into the hall?'

`Murderer saw the key and turned it to prevent the body being discovered before he had a chance to get well away.'

He paused, and his face assumed a look of cunning which sat oddly on the aquiline, somewhat supercilious features. He said: `An alternative theory is that Maybrick locked himself in. Expected a secret visitor and didn't want to be disturbed. One ques- tion I have to ask you, my boy. Rather deli- cate. How well did you know Maybrick?'

Paul said: 'Only slightly. He's a second cousin.'

`You trusted him? Forgive my asking.'

`We had no reason to distrust him. My grandmother wouldn't have asked him to sell the coins for her if she'd had any doubts. He is family. Distant, but still fami- ly.'

`Of course. Family.' He paused, then went on: 'It did occur to me that this could have been a staged attack which went over the top. He could have arranged with an accomplice to steal the coins. We're asking the Yard to look at his London connec- tions.'

I was tempted to say that a faked attack which left the pretend victim with a pulped brain had gone spectacularly over the top, but I remained silent. The Chief Constable could hardly order me out of the sitting- room — after all, I had been present at the discovery of the body — but I sensed his disapproval at my obvious interest. A young woman of proper feeling would have followed my grandmother's example and taken to her room.

Paul said: 'Isn't there something odd about that smashed watch? The fatal blow to the head looked so deliberate. But then he strikes again and smashes the hand. Could that have been to establish the exact time of death? If so, why? Or could he have altered the watch before smashing it? Could Maybrick have been killed later"?'

The Chief Constable was indulgent to this fancy: 'A bit far-fetched, my boy. I think we've established the time of death pretty accurately. Bywaters puts it at between ten and eleven, judging by the degree of rigor. And we can't be sure in what order the killer struck. He could have hit the hand and shoulder first, and then the head. Or he could have gone for the head, then hit out wildly in panic. Pity you didn't hear anything, though.'

Paul said: 'We had the gramophone on pretty loudly and the doors and walls are very solid. And I'm afraid that by 11.30 I wasn't in a state to notice much.'

As Sir Rouse rose to go, Paul asked: 'I'll be glad to have the use of the library if you've finished with it, or do you want to seal the door?'

`No, my boy, that's not necessary. We've done all we need to do. No prints, of course, but then we didn't expect to find them. They'll be on the weapon, no doubt, unless he wore gloves. But he's taken the weapon away with him.' The house seemed very quiet after the police had left. My grandmother, still in her room, had dinner on a tray and Paul and I, perhaps unwilling to face that empty chair in the dining-room, made do with soup and sandwiches in the sitting-room. I was restless, physically exhausted; I was also a little frightened. It would have helped if I could have spoken about the murder but Paul said wearily: `Let's give it a rest. We've had enough of death for one day.'

So we sat in silence. From 7.40 we lis- tened to Radio Vaudeville on the Home Service. Billy Cotton and his Band, the BBC Symphony Orchestra with Adrian Boult. After the nine o'clock news and the 9.20 War Commentary, Paul murmured that he'd better check with Seddon that he'd locked up.

It was then that, partly on impulse, I made my way across the hall to the library. I turned the door-handle gently as if I `Because I want to find out whether you've been naughty or nice, Tommy. That's why I want you to take this lie detector test . . feared to see Rowland still sitting at the desk sorting through the coins with avari- cious fingers. The black-out curtain was drawn, the room smelled of old books, not blood. The desk, its top clear, was an ordi- nary unfrightening piece of furniture, the chair neatly in place. I stood at the door convinced that this room held a clue to the mystery.

Then, partly from curiosity, I moved over to the desk and pulled out the drawers. On either side was a deep drawer with two shallower ones above it. The left was so crammed with papers and files that I had difficulty in opening it. The right-hand deep drawer was clear. I opened the small- er drawer above it. It contained a collection of bills and receipts. Riffling among them I found a receipt for £3,200 from a London coin dealer listing the purchase and dated five weeks previously.

There was nothing else of interest. I closed the drawer and began pacing and measuring the distance from desk to the French windows. It was then that the door opened almost soundlessly and I saw my cousin.

Coming up quietly beside me, he said lightly: 'What are you doing? Trying to exorcise the horror?'

I replied: 'Something like that.'

For a moment we stood in silence. Then he took my hand in his, drawing it through his arm. He said: `I'm sorry, cousin, it's been a beastly day for you. And all we wanted was to give you a peaceful Christmas.'

I didn't reply. I was aware of his near- ness, the warmth of his body, his strength. As we moved together to the door I thought, but did not say: 'Was that really what you wanted, to give me a peaceful Christmas? Was that all?'

Previous page

Previous page