Ephemera

Surrealist Games (Compiled and presented by Alastair Brotchie, edited by Mel Gooding, Redstone Press, boxed, ┬Ż14.95)

Hardened sunbeams

John Henshall

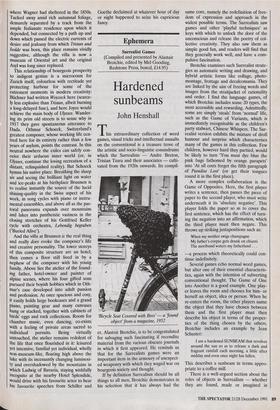

This extraordinary collection of word games, visual tricks and intellectual assaults on the conventional is a treasure trove of the artistic and socio-linguistic conundrums which the Surrealists ŌĆö Andre Breton, Tristan Tzara and their associates ŌĆö culti- vated from the 1920s onwards. Its compil- `Bicycle Seat Covered with Bees' ŌĆö a found object' from a magazine, 1952 er, Alastair Brotchie, is to be congratulated for salvaging such fascinating if recondite material from the various obscure journals in which it first appeared. He reminds us that for the Surrealists games were an important item in the armoury of unexpect- ed weaponry with which they waged war on bourgeois society and thought. If by definition Surrealism should be all things to all men, Brotchie demonstrates in his selection that it has always had the same core, namely the redefinition of free- dom of expression and approach in the widest possible terms. The Surrealists saw games and other 'playful techniques' as keys with which to unlock the door of the unconscious and release the poetry of col- lective creativity. They also saw them as simple good fun, and readers will find that they generally work wen, and have a com- pulsive fascination.

Brotchie examines such Surrealist strate- gies as automatic writing and drawing, and hybrid artistic forms like collage, photo- montage, frottage and decalcomania. They are linked by the aim of freeing words and images from the straitjacket of rationality and order. I find the language games, of which Brotchie includes some 20 types, the most accessible and rewarding. Admittedly, some are simply 'steals' from 'normal' life, such as the Game of Variants, which is immediately recognisable as the children's party stalwart, Chinese Whispers. The Sur- realist version exhibits the mixture of droll humour and surprise which characterises many of the games in this collection. Few children, however hard they partied, would be likely to turn 'You must dye blue the pink bags fathomed by orange parapets' into 'At all costs forget the fifth paragraph of Paradise Lost' (or get their tongues round it in the first place).

A more complex collaboration is the Game of Opposites. Here, the first player writes a sentence, then passes the piece of paper to the second player, who must write underneath it its 'absolute negative'. This player folds the paper so as to cover the first sentence, which has the effect of turn- ing the negation into an affirmation, which the third player must then negate. This throws up striking juxtapositions such as:

When my mother swigs champagne My father's corpse gets drunk on chianti The moribund waters my fatherland .. .

ŌĆöa process which theoretically could con- tinue indefinitely.

Several games echo normal word games, but alter one of their essential characteris- tics, again with the intention of subverting conventional thought. The Game of One into Another is a good example. One play- er leaves the room and chooses for him- or herself an object, idea or person. When he re-enters the room, the other players name the object that they have chosen between them and the first player must then describe his object in terms of the proper- ties of the thing chosen by the others. Brotchie includes an example by Jean Schuster:

I am a hardened SUNBEAM that revolves around the sun so as to release a dark and fragrant rainfall each morning, a little after midday and even once night has fallen.

This describes a sunbeam in terms appro- priate to a coffee There is a well-argued section about the roles of objects in Surrealism ŌĆö whether they are found, made or imagined in dreams and similar states. Text and illustra- tion fuse so well that some of the pho- tographs Brotchie includes sit in the book as surreal 'founds' in their own right. They include Meret Oppenheim's bicycle seat covered with bees, and Yves Tanguy's 'The Tabernacle', a nightmarish monkey's head protruding from a rectangular container covered in what looks like an old cardigan and with a candle-holder jutting from each side like an arm. There is also a simultane- ously symbolic and farcical photograph of `Benjamin Peret in the Act of Insulting a Priest', where a moment in time becomes the object itself.

Some of the categories of verbal investi- gation are inevitably little more than a pre- dictably bizarre Surrealist reworking of a familiar idea. These include Peret's 'Provo- cation' which runs, 'If you see a priest being beaten, make a wish' (Peret evidently was not keen on priests) and his new super- stations like, 'When passing a police sta- tion, sneeze loudly to avoid misfortune'. There are the new proverbs he construed with Paul Eluard ŌĆö 'Faithful as a filleted cat' or 'One good mistress deserves anoth- er'. The Little Surrealist Dictionary contains bons mots such as 'Beliefs are ideas going bald'. They may seem fey, even trite, but Brotchie is careful to see they make their points about the many possibilities and seemingly non-existent boundaries of Sur- realism.

Previous page

Previous page