Four fishy islands

Murray Sayle

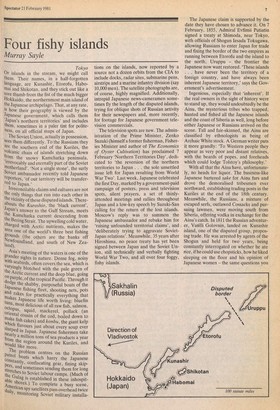

Tokyo Or islands in the stream, we might call them. Their names, in a half-forgotten language, are Kunashir, , Etorofu, Habomai and Shikotan, and they stick out like a sore thumb from the fist of the much bigger Hokkaido, the northernmost main island of the Japanese archipelago. That, at any rate, iS how their geography is viewed by the Japanese government, which calls them 'Japan's northern territories' and includes them, sometimes in a paler tint for politeness, on all official maps of Japan.

The Soviet Union, actually in possession, sees them differently. To the Russians they are the southern end of the Kuriles, the volcanic chain of islands stretching down from the snowy Kamchatka peninsula, 'irrevocably and eternally part of the Soviet motherland'. 'Not a single stone', the surly Soviet ambassador recently told Japanese reporters, 'of our territory will be transferred to Japan.' Irreconcilable claims and cultures are not the only things that run into each other in the vicinity of these disputed islands. Thereabouts the Kuroshio, the 'black current', Japan's answer to the Gulf Stream, meets the Kamchatka current descending from the Bering Strait. The upwelling cold water, charged with Arctic nutrients, makes the area one of the world's three best fishing grounds (the others are the banks off Newfoundland, and south of New Zealand).

Asia's meeting of the waters is one of the grander sights in nature. Dense fog, noisy With seabirds, often covers the sea, which is varyingly blotched with the pale green of the Arctic current and the deep blue, going on purple, of the tropical Pacific. Through it dodge the shabby, purposeful boats of the Japanese fishing fleet, shooting nets, pots and rakes for practically everything that makes Japanese life worth living: bluefin tuna, most delicious of all raw fish, salmon, octopus, squid, mackerel, pollack (an oriental cousin of the cod, boiled down to make fish cakes) and konbu, the giant kelp which flavours just about every soup ever slurped in Japan. Japanese fishermen take nearly a million tons of sea products a year from the region around the Kuriles, and would like more. The problem centres on the Russian Patrol boats which harry the Japanese constantly, confiscating gear, fining skipPers, and sometimes sending them for long sthe tretches to Soviet labour camps. (Much of Gulag is established in these inhospit abl 'fi e shores.) To .complete a busy scene, ,imerican spy satellites pass overhead twice 1 1y, monitoring Soviet military installa tions on the islands, now reported by a source not a dozen orbits from the CIA to include docks, radar sites, submarine pens, airstrips and a marine infantry division (say 10,000 men). The satellite photographs are, of course, highly magnified. Additionally, intrepid Japanese news-cameramen sometimes fly the length of the disputed islands, trying for oblique shots of Russian activity for their newspapers and, more recently, for footage for Japanese government television commercials.

The television spots are new. The administration of the Prime Minister, Zenko Suzuki (himself a former fisherman, Fisheries Minister and author of The Economics of Oyster Cultivation) has proclaimed 7 February 'Northern Territories Day', dedicated to 'the reversion of the northern territories to Japan . . . the sole unsettled issue left for Japan resulting from World War Two'. Last week, Japanese celebrated the first Day, marked by a government-paid campaign of posters, press and television spots, silent prayers, a set of thinlyattended meetings and rallies throughout Japan and a low-key speech by Suzuki-San calling for the return of the lost islands. Moscow's reply was to summon the Japanese ambassador and rebuke him for 'raising unfounded territorial claims', and 'deliberately trying to aggravate SovietJapan relations'. Meanwhile, 35 years after Hiroshima, no peace treaty has yet been signed between Japan and the Soviet Union, still technically and verbally fighting World War Two, and all over four foggy, fishy islands, The Japanese claim is supported by the date they have chosen to advance it. On 7 February, 1855, Admiral Evfimii Putiatin signed a treaty at Shimoda, near Tokyo, with officials of Shogun Iesada Tokugawa, allowing Russians to enter Japan for trade and fixing the border of the two empires as running between Etorofu and the island to the north, Uruppu — the frontier the Japanese now want restored. 'These islands . . . have never been the territory of a foreign country, and have always been inherent Japanese territory,' says the Government's advertisement.

Ingenious, especially that 'inherent'. If the real owners in the sight of history were to stand up, they would undoubtedly be the Ainu, the mysterious tribes who trapped, hunted and fished all the Japanese islands and the coast of Siberia as well, long before either Japanese or Russians arrived on the scene. Tall and fair-skinned, the Ainu are classified by ethnologists as being of Archaic White stock. A German writer puts it more grandly: 'To Western people they appear as very poor and distant relatives, with the beards of popes, and foreheads which could lodge Tolstoy's philosophy.'

With all that the Ainu have, unfortunately, no heads for liquor. The business-like Japanese bartered sake for Ainu furs and drove the demoralised tribesmen ever northward, establishing trading posts in the Kuriles at the end of the 18th century. Meanwhile, the Russians, a mixture of escaped serfs, outlawed Cossacks and pursuing lawmen, were moving south from Siberia, offering vodka in exchange for the Ainu's catch. In 1811 the Russian adventurer, Vasilli Golovnin, landed on Kunashir island, one of the disputed group, proposing trade. He was arrested by agents of the Shogun and held for two years, being constantly interrogated on whether he ate rice, if he could use chopsticks, how he liked sleeping on the floor and his opinion of Japanese women — the same questions you

will get today, in fact, on any Tokyo underground.

The 1855 treaty, as it turned out, was only a truce. Japanese continued to push north, Russians south, and in 1875 they struck a new deal: Russia got the whole of Sakhalin island, immediately north of Japan (where Alexander Solzhenitsyn served part of his time) and the Japanese the entire Kurile island chain. On the basis of this treaty, the Japan Communist Party now demands all the Kuriles back from their one-time Soviet patrons.

Rival manifest destinies, as ever, came to blows. In 1905 Japan (with British-built ships, guns and navy instructors) scored the first victory by Asians over Europeans since the time of Genghiz Khan, upsetting betting men all over the world and 'casting a long shadow into the future. Japan took half of Sakhalin and Russia's toehold in China as war prizes.

There matters stood for 40 years, while Russia was busy with revolution at home and Japan with building her empire in Asia. In September 1940, Japan joined that year's other two big winners, Germany and Italy, in 'the pact of steel'. The following April, Japan and the Soviets signed a five-year non-aggression treaty, securing Russia's rear for the war in Europe and Japan's for the seizure of the colonial empires of Britain, France and Holland, all busy elsewhere.

Almost three years to the day after Pearl Harbour, on 14 December 1944, Averell Harriman was in Moscow to transact some business with Joe Stalin. The atom bomb was still an untested, two-billion-dollar gamble, and Harriman had been sent by his boss, President Roosevelt, to find out Stalin's price for joining the war against Japan. Russian intervention, it was believed, would save the lives and limbs of up to two million American boys. As Britain, China and the US had already agreed in Cairo that 'Japan will be expelled from all the territories which she has taken by force and greed', which covered a lot of Asia, Harriman could afford to be generous.

'Stalin', reported Harriman the next day 'went into the next room and brought out a map. He said that the Kurile islands and lower Sakhalin controlled the approaches to Vladivostok, that he considered that the Russians were entitled to protection for their communications to this important port, and that all outlets to the Pacific were now blocked by the enemy.'

Heartened that Stalin was not asking for Hawaii and San Francisco, Harriman agreed to throw in Outer Mongolia, a lease on Port Arthur (in China) as a naval base, and a half-share in the Chinese eastern railway on the understanding that 'the pre-eminent interests of the Soviet Union should be safeguarded'. Uncle Joe Was getting back all that the Czar had lost in 1905, with a bonus, and on those terms he agreed that 'two or three months after Germany has surrendered . . . the Soviet Union shall enter the war against Japan'. The delay was to allow the Russians to transfer their armies, particularly the tanks, from the ruins of Germany.

The Japanese were not, of course, informed of this private bit of business. The Potsdam Declaration of 26 July 1945, threatened them with 'utter devastation of the Japanese homeland', by means unspecified (the first atom bomb had gone off with an awesome bang in the New Mexico desert only ten days before) unless they surrendered, in which case Japanese sovereignty would be limited to the four main Japanesepacked islands 'and such minor islands as we determine'.

On 6 August, 1945, Hiroshima was atom-bombed. 'This is the greatest thing in history,' whooped Harry Truman, who had inherited the mystery weapon from Roosevelt. His chief of staff, General George Marshall, told him the Russians were no longer needed, 'but if they intend to enter the war they cannot be stopped'. Two days after Hiroshima, on 8 August, Stalin's tank divisions rolled over the Manchurian border. Nagasaki's turn came on 9 August, and on 14 August, with the Japanese army in China crumbling, Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration, 'minor islands' and all, and unconditionally surrendered,

Why? Future generations are not likely to view the events of that fateful week as the finest hour of either the US or the USSR, although the Japanese had at different times given both provocation, beyond doubt. American versions of how the war ended play down the Russian intervention, The latest Soviet one, in the magazine Far Eastern Affairs, by General S.P. Ivanov, who was there, says The defeat of Japanese forces in Japan and on the Asian mainland was unthinkable without Soviet participation' and that the idea behind the Americans' atom bomb was to 'intimidate the whole world, including the Soviet Union'. Which ended the war, the Americans' bomb, or the Russians' invasion?

Both sides, of course, want to justify shabby deeds by shiny results, Apart from Emperor Hirohito, the people who really know are all dead, and the Emperor has his own reasons for keeping mum. From Japan's viewpoint, the taking out of two minor provincial towns, however flashily, had little effect on Japan's capacity to fight on. Everywhere else, in that war, and every war since, terror bombing of civilians has hardened their resolve. Fear that Japan would be partitioned between the Russians and the rest, as Germany had been, certainly and powerfully influenced the Japanese leadership. The best conclusion seems to be: the new bombs were depressing, the Russian intervention decisive. These events were, however, probably related. Until the next set of Russian revolutionaries throw open the Kremlin archives, we can't be sure, but a lot of evidence suggests that the Russians read Hiroshima as the signal to get going while the party lasted. Their preparation, certainly for the seizure of the promised islands, seem to have been woefully inadequate. The mainland attacks began without the customary Russian artillery bombardments, in pouring rain, and two weeks after Japan had surrendered the Red Army was still slogging forward to its objectives. The Japanese, writes General Ivanov, had 'merely professed capitulation'. For what it was worth, the Soviet Japanese non-aggression treaty still had nearly a year to run. The Soviet invasion of the promised Kuriles did not get going until early Septent' ber 1945. On 2 September, while Soviet General K.N. Derevyanko, in boots and riding breeches, was playing a walk-on part in General Douglas MacArthur's surrender spectacular aboard the USS Missouri (christened by Margaret Truman after Harry's horhe state), Russian troops were hopping from island to island, using the same landing craft over and over again, and pausing briefly before tackling Etorofu not, as the Japanese now claim, because they knew they were doing the wrong thing, but to scratch together enough fishing boats for a force big enough to secure the island which is more than 100 miles long. As the Russian invaders arrived, the 16,000 Japanese residents fled, leaving General 1vanov's men to liberate volcanic mountains, rocky beaches, fog — and fish. The Japanese have been claiming the disputed four islands back ever since, and they seemed to be making progress in 1956, When the joint declaration which reestablished diplomatic relations between the two old enemies 'agreed to return the Habomai islands and Shikotan to Japan, Whose actual accession to Japan will be Subject to the conclusion of a peace treaty between Japan and the Soviet Union' — meaning that the Japanese got the two smaller islands back in return for signing the two big ones over to the Soviets in perpetuity. However, the new Soviet line, 'not a single stone for Japan', seems to eliminate even this modest pis aller.

Why do the Soviets want the islands? Things have changed a bit, of course, since the pally days of Yalta and Potsdam, and the Americans are now Stalin's 'enemy blocking all outlets to the Pacific', or doing their best. The Soviet Union has become a great naval power in the Far East and, in Place of the impoverished fishing boat fleet Which took the islands in 1945, now deploys an aircraft carrier, the Minsk, and more than 150 submarines, 30 of them nuclear, Again, I have not counted them personally, and I get my figures from a friend who knows a man who is rumoured to work for Charlene in the Ionosphere with a sAtellite. The Russians certainly have one nuclear submarine out here, because an Echo-1 surfaced, with a fire aboard, last year and Was brazenly towed through Japanese home waters back to Vladivostok. The purpose of the Russians' underwater armada is clearly to break up any sea-linked Chinese-Japanese-American combination against them, and from the Soviet viewPoint returning the islands to Japan would be tantamount to giving them to Uncle Sam and opening the Sea of Okhotsk, and thus , Vladivostok, to the fleet of the imperialists. Eiesides, a deal is a deal is a deal. A commentator in Pravda on 3 February dismisses the Shimoda Treaty of 1855, ich gives the islands to Japan, as an unjust treaty forced on Russia when her P°wer was at a low ebb.' „, Weil, the Japanese reply, our position "asn't exactly rosy in 1945 when we accepted the Potsdam Declaration, which YvvaY made no mention of the secret seta carve-up of Japanese territory, It ,ems to the Japanese side a bit much to ueseribe the peaceful liquor-trading coliOenisation by the Shoguns' men as 'territora.s taken by force and greed' — how, after thil, did the Russians acquire Siberia, or for aTt matter, the Americans Manhattan? n Japanese old enough to remember have arer forgiven the Russians for their uninoeral breaking of the non-aggression pact, nevatr for the 200,000 Japanese POWs who _mer Came home from the Siberian labour edo_ P.s. The term older Japanese use is kaji Steals' or 'fireside thief', someone who yur o household goods when your use is on fire. It's about the nastiest thing a Japanese can call anyone, although the same people, if pushed, will concede that Japan did her share of fireside filching in the past.

But most of today's younger Japanese don't know as much as tireless readers of the Spectator about the islands dispute, and care less. Why, then, does Prime Minister Suzuki make a big thing out of it now? Because, locally, the Russians are well on the way to getting their annexation accepted. Transport difficulties prevent them using much of the fish themselves (although a factory on Shikotan is processing finest Pacific cod for fertiliser) and so they have something to trade with — unofficial permission for friendly Japanese to fish the rich waters. In return; the Japanese boats bring transistor radios, hi-fi sets, watches, pantyhose, copying machines, typewriters and even, it is said, motor bikes and small cars, just as their ancestors traded with the Ainu long ago (Russians don't seem to care for sake.) To facilitate this lucrative clandestine trade, Japanese fishermen have built 'Soviet friendship halls' in many of the northern ports, and some have gone further and supply the KGB agents with intelligence on movements of American and Japanese troops in Northern Japan. Japanese underworld figures, according to the magazine Shukan Shincho, ferry Japanese bar hostesses over to the lonely Russians, and in return are allowed to issue 'licences' to fish in Russian waters, charging £40,000 to £80,000 per vessel. Japanese spooks in turn try to pass disinformation to the Russians and, last month, a Japanese police official, said to be entangled in this risky game, hanged himself. So, while the Peking People's Daily has cheered Prime Minister Suzuki on, charging that the four islands have been 'turned into a Soviet hegemonist fortress', the local fishermen who theoretically stand to benefit most from their recovery have shown the least enthusiasm. The president of the local fisheries co-operative, Shoichi Takamoto, stunned officials in Tokyo by urging that Japan should abandon its claims to the two bigger islands in return for fishing rights around the smaller ones. 'We can eat fish, but we can't eat rocks', he argued, with admirable Japanese practicality, We are not, then, looking at the spark that will touch off World War Three, at least not immediately. Indeed, the primary target of the Japanese government's 'Northern territories', campaign seeps to be, not the hard-hearted Soviets, but their own people, apparently close to accepting things as they are and letting a foggy corner of the fatherland go by default.

Meanwhile the Ainu, who probably have the best claim of all (the names of the disputed islands are in the Ainu language, for example), are not well placed to advance it. Many have interbred with the Japanese, who are for this reason said to be hairier than other Asians. The few hundred pure-blood Ainu left in Northern Japan are a sad tourist attraction, dividing their time between carving wooden bears, symbol of lost tribal pride, and drinking sake. Over on the Russian side of the border, wherever it should rightfully run, the surviving Ainu in their sober moments study Marx and work intermittently to build socialism. Caught between two egotistical energetic empires, the losers can expep little. Not even four foggy fishy islands.

Previous page

Previous page