No easy riding for those who stayed behind

Robert Oakeshott

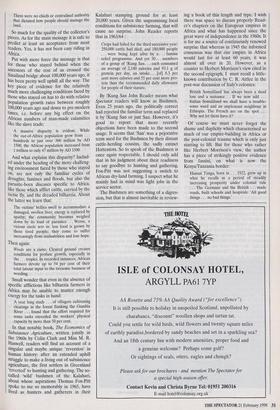

AFRICA: BIOGRAPHY OF A CONTINENT by John Reader Hamish Hamilton, £30, pp. 840

Several strands of evidence — fossil, genetic and linguistic — point persuasively to the conclusion that every person alive today Is descended from a population of anatomically modern humans that existed only in Africa about 100,000 years ago.

(John Reader on our shared African

origin) We are friends of the jolly old Empire and we are going to stick to it.

(Herbert Morrison after Labour had come to power in 1945) I think most of the surviving 'wild' Bushmen would prefer to call hunting and gathering a day.

(Thomas Fox-Pitt to the reviewer in 1965, soon after his retirement as Secretary of the then Anti- Slavery and Aborigine Protection Society)

This is a towering work of popular, easy to read scholarship and it is wonderfully illustrated by the author's own black and white photographs. I can warmly recom- mend it to general readers as well as to Africa specialists. Though I shouldn't say so because I haven't got a set, it would make a splendid series on television.

My guess is that even the most knowl- edgeable specialist will find a fair number of new collector's pieces. For me, a semi- specialist, a prize example is the island of Ukara in Lake Victoria with its astonishing ownership, agricultural and political arrangements:

Each household farms an average of about 2.5 hectares.

Ninety-eight point six per cent of the total land area is productively used.

Every tree is privately owned [which] ensures that the use of this indispensable resource is sustainable.

With the exception of springs, river and pond water, and the main trackways between villages, every square metre of the island is privately owned.

[The islanders] each spend an average of more than ten hours a day on agricultural tasks throughout the year. There were no chiefs or centralised authority that dictated how people should manage the land.

So much for the quality of the collector's pieces. As for the main message it is safe to predict at least an acceptance from most readers. Yes, it has not been easy riding in Africa.

Put with more force the message is that for those who stayed behind when the ancestors of the rest of us crossed the Sinailand bridge about 100,000 years ago, it has been pretty well uphill all the way. The key piece of evidence for the relatively much more challenging conditions faced by those who stayed on has to do with relative population growth rates between roughly 100,000 years ago and down to pre-modern times, i.e. before any big effect on the African numbers of man-made calamities like the slave trade:

A massive disparity is evident. While the out-of-Africa population grew from . hundreds to just over 300 million by AD 1500, the African population increased from 1 million to only 47 million by AD 1500.

And what explains this disparity? Includ- ed under the heading of the more challeng- ing environment faced by those who stayed on, are not only the familiar cycles of droughts, famines and floods, but also the parasite-born diseases specific to Africa, like those which afflict cattle, carried by the tsetse fly, and the dreaded bilharzia. About the latter we learn that: The victims' bellies swell to accommodate a damaged, swollen liver; energy is replaced by apathy; the community becomes weighed down by its load of parasites .. . Worse, a vicious circle sets in: less food is grown by these tired people; they come to suffer increasingly from malnutrition and lose hope.

Then again: Weeds are a curse. Cleared ground creates conditions for profuse growth, especially in the ... tropics. In recorded instances, African farmers devote up to 54 per cent of their total labour input to the tiresome business of weeding.

Small wonder that even in the absence of specific afflictions like bilharzia farmers in Africa may be unable to muster enough energy for the tasks in hand:

A year long study .. . of villagers cultivating clearings in the forest flanking the Gambia River . .. found that the effort required for some tasks exceeded the workers' physical capacity by more than 50 per cent.

In that notable book, The Economics of Subsistence Agriculture, written jointly in the 1960s by Colin Clark and Miss M. R. Haswell, readers will find an account of a singular and maybe unique 'reversion' in human history: after an extended uphill struggle to make a living out of subsistence agriculture, the first settlers in Greenland `reverted' to hunting and gathering. The so- called 'wild' bushmen of the Kalahari, about whose aspirations Thomas Fox-Pitt spoke to me so memorably in 1965, have lived as hunters and gatherers in their Kalahari stamping ground for at least 20,000 years. Given the unpromising local conditions for subsistence farming, that will cause no surprise. John Reader reports that in 1963/64 :

Crops had failed for the third successive year: 250,000 cattle had died, and 180,000 people . . . were being kept alive by a . .. famine relief programme And yet 30 . . . members of a group of !Kung San . . each consumed an average of 2,140 calories and 93.1 g of protein per day, an intake ... [of] 8.3 per cent more calories and 55 per cent more pro- tein than the recommended daily allowance for people of their stature.

By !Kung San John Reader means what Spectator readers will know as Bushmen. Even 25 years ago, the politically correct had rejected the familiar term and replaced it by !Kung San or just San. However, it's good to report that more recently objections have been made to the second usage. It seems that 'San' was a pejorative term used for the Bushmen by their distant cattle-herding cousins, the sadly extinct Hottentots. So to speak of the Bushmen is once again respectable. I should only add that in his judgment about their readiness to say goodbye to hunting and gathering, Fox-Pitt was not suggesting a switch to African dry-land farming. I suspect what he mainly had in mind was light jobs in the service sector.

The Bushmen are something of a digres- sion, but that is almost inevitable in review- ing a book of this length and type. I wish there was space to discuss properly Read- er's chapters on the European empires in Africa and what has happened since the great wave of independence in the 1960s. It is for me a source of continuously renewed surprise that whereas in 1945 the informed consensus was that our empire in Africa would last for at least 60 years, it was almost all over in 20. However, as a counter to Herbert Morrison's view cited in the second epigraph, I must recall a little- known contribution by C. R. Attlee in the post-war discussion of Italy's colonies:

British Somaliland has always been a dead loss and a nuisance. . If we now add . Italian Somaliland we shall have a trouble- some ward and an unpleasant neighbour in Ethiopia. The French are on the spot . Why not let them have it?

Of course we must never forget the shame and duplicity which characterised so much of our empire-building in Africa or the post-colonial trauma which is only just starting to lift. But for those who rather like Herbert Morrison's view, the author has a piece of strikingly positive evidence from Jassini, on what is now the Kenya/Tanzania border:

Hassan Tanga, born in 1922, grew up in what he recalls as a period of steadily increasing prosperity under colonial rule . . . The Germans and the British .. . made roads, built schools and hospitals: 'All good things .. . no bad things.'

Previous page

Previous page