A TALENT TO ABUSE

Outsiders: a profile of

Dennis Skinner, enemy

of party promise

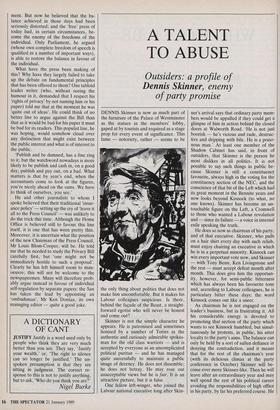

DENNIS Skinner is now as much part of the furniture of the Palace of Westminster as the statues in the members' lobby, gaped at by tourists and required as a stage prop for every event of significance. This fame — notoriety, rather — seems to be the only thing about politics that does not make him uncomfortable. But it makes his Labour colleagues suspicious. Is there, behind the facade of the Beast, a straight- forward egotist who will never be honest and come out?

Skinner is not the simple character he appears. He is patronised and sometimes lionised by a number of Tories as the authentic and curiously admirable spokes- man for the old class warriors — and is accepted by everyone as an uncomplicated political puritan — and he has managed quite successfully to maintain a public image of decency. He does not dissemble; he does not betray. He may roar out unacceptable views but he is fair. It is an attractive picture, but it is false.

One fellow left-winger, who joined the Labour national executive long after Skin- ner's arrival says that ordinary party mem- bers would be appalled if they could get a glimpse of him in action behind the closed doors at Walworth Road. 'He is not just boorish — he's vicious and rude, destruc- tive and dripping with bile. He is a poiso- nous man.' At least one member of the Shadow Cabinet has said, in front of outsiders, that Skinner is the person he most dislikes in all politics. It is not possible to say such things in public be- cause Skinner is still a constituency favourite, always high in the voting for the constituency section of the NEC, and the conscience of that bit of the Left which had its great moment in the Bennite years and now looks beyond Kinnock (to what, no one knows). Skinner has become an un- touchable figure on the Left, a Cromwell to those who wanted a Labour revolution and — since its failure — a voice in internal exile speaking the truth.

He does so now as chairman of his party, and of that executive. Skinner, who pulls on a hair shirt every day with such relish, must enjoy chairing an executive in which he is in a perpetual minority. Kinnock can win every important vote now, and Skinner — with Tony Benn, Ken Livingstone and the rest — must accept defeat month after month. This does give him the opportun- ity, however, for semi-public bitterness which has always been his favourite tone and, according to Labour colleagues, he is particulary bitter these days: the word Kinnock comes out like a sneer.

As chairman he is not engaged on the leader's business, but in frustrating it. All his considerable energy is devoted to promoting that section of the party which wants to see Kinnock humbled, but simul- taneously he protests, in public, his utter loyalty to the party's aims. The balance can only be held by a sort of sullen defiance in denying the contradiction, and it means that for the rest of the chairman's year (with its delicious climax at the party conference in October) Skinner will be- come ever more Skinner-like. Then he will leave after an extraordinary year and may well spend the rest of his political career avoiding the responsibilities of high office in his party, by far his preferred course. He has a near obession about staying away from power because, as we know, power corrupts.

But so do such single-minded crusades. Skinner, famous for his bawling at question time, his ulcer and his sharp wit, is con- vinced that he is one of the few parlia- mentarians who has kept faith with his People since he came to Westminster after two decades in the Derbyshire pits — and he has some right to boast about it. But the self-righteousness which comes with it sits uneasily alongside the humility which he Claims for himself.

In a Parliament in which the smell of the ad men's soft soap is now overpowering and where the backhanders are now so obvious that they are hardly noticed, it is not surprising that Skinner has often been considered refreshingly honest: he has accepted no free trips, at home or abroad, and will not accept hospitality (even from journalists who mean well) and he has been unrelenting — as well as ingenious in his pursuit of jiggery-pokery anywhere Where public money is spent. In itself, this is admirable, but the moral posturing which goes with it sits uneasily on the shoulders of someone who is capable of plotting with the best of them on the NEC and of conspiring happily in Labour's internal battles in a way which stretches his claims of loyalty well beyond breaking point.

Some of his admirers in the party were appalled a few years ago when he used the considerable platform (as it then was) of the Tribune rally at the annual conference to boast in the course of an anti-EEC tirade that he had no passport and saw no reason for having one (he once went to Vienna for an international mineworkers' conference but left early, paying his own fare home, because abroad disagreed with him so much). It was xenophobia on a grand scale comparable with the stupidest of outbursts from the nationalist Right and was a surprising admission by Skinner that he was not interested in the ideas of the emerging mainstream on the Left because they did not encompass his own prejudices. There is a famous newspaper picture of the Wilson era. It shows two disgruntled left-wingers on the empty Government benches stretched out in sullen protest at the march of all their colleagues along the corridor to the Lords for the Queen's Speech — Skinner and beside him Kin- flock, In the years that followed Skinner could not have made Kinnock's moves Partly because his convictions about the socialism of the class struggle have never wavered but also because he is genuinely fearful of normal political ambition, and desperately worried at the prospect of compromise or sell-out. Political co- operation, in his view, is hardly ever worth the risk. That he took the party chair- manship was a surprise, because it is seldom possible to see anything but a destructive force at work in him.

Yet this is the figure who has become the

object of some genuine affection in the Commons. It has happened because of his genuine wit and a sense of humour which shows up most of the amateur joke mer- chants on both sides, but which seems a puzzle. On the NEC, at a normal meeting, he can appear the model of the Earnest Left, self-regarding and humourless, stuck in his posture of the anxious zealot. In the Commons, on a good day, he sparkles.

Up in Bolsover there is no puzzle about this. Skinner is a straightforward tribune of the people. He is seen as a stolid defender of the weak against the strong and is accepted widely as someone who is only nasty to the extent that it is necessary to his work. He has lived in the Clay Cross area for all his adult life, progressing from his act round the working men's clubs where he performed celebrated imitations of Slim Whitman and Frankie Lane in his strange, tight tenor to his place, after 1970, as the MP whose values are not corrupted by the South and the political establishment. So it seems up there. His defence of the rebel Clay Cross councillors, his unwavering support for the NUM (to which he gave his whole parliamentary salary in 1984-85 dur- ing the strike) is all of a piece with his parliamentary behaviour. The humour, in Bolsover, isn't seen as contradictory; it is thought to be evidence of quite how aware he is of the need to put on a tough act though he is as soft as everyone else underneath.

This is not a view shared at Westminster. Kinnock and his supporters see Skinner as an almost wholly malign influence, some of them even arguing — only half jokingly — that he is permanently awash with bile as a result of the ulcer from which he has suffered for years. Even more wickedly, they point to his famous fall from his bike a few years ago and say that he banged his head so badly that it made him worse than he already was.

While his family life in Bolsover, and his political consistency over three decades make him seem a man without a pose, his opponents elsewhere say that the two sides of his national personality are irreconcil- able. For example, when he appeared on Any Questions on Radio 4 and on Question Time on BBC television (both for the first time quite recently) he prepared for the performances with meticulous care, re- hearsing the jokes — and was justly proud afterwards of the success of the act. He does play the political game, but he doesn't like to be seen to.

He is able, however, to talk enthusiasti- cally about other politicians in all parties and to offer incisive judgments about their behaviour, their chances, the game-plans. Yet, with outsiders, it is always interrupted by some bitter outburst as if he cannot bring himself to relax openly for more than a few minutes at a time.

So there it is. In Bolsover, the most straightforward character you could im- agine. At Westminster, a plotter with chips on both shoulders and a penchant for personal nastiness. To Skinner there is no contradiction because he regards West- minster as removed from the real world and therefore a place where you have to behave out of character, though he adores it. That is how he justifies everything — even the disloyalty to his party, through his battles with the leader and his satraps which he pursues in ruthless ways.

Skinner is a thoroughly old-fashioned figure, Thatcherism. He fears any accom- modation with changes in Labour's think- ing which betray the values and spirit of Clause 4 of the party constitution, though he knows such changes are irreversible. His instincts react against all he sees around him and he knows he will always be disaffected. In Labour Party politics, it is hard to think of anything that would make him happy.

Yet he is no bore. Many of those on the authoritation Left are unspeakably dull; Skinner is not. He is occasionally very funny, perceptive about politics and to those he sees as the weak, he is kind. This all saves him from the obscurity which most self-regarding zealots deserve. Labour's problem with the Beast of Bol- sover is that although his individuality does grace the political scene in his destructive ways, from the stage loutishness to the frequent disloyalties, he insists that his party must pay a high price for it.

Previous page

Previous page