A MAN FOR ALL REASONS

A profile of Lord Wyatt of Weeford, chairman of the Tote, and the News of the World's Voice of Reason LAST Sunday the News of the World devoted eight pages to the sordid revela- tions of Prince Charles's valet. By the stan- dards of the paper which has made a fetish of intruding into the private affairs of the royal family it was business as usual. Simi- larly, on page 11, there was the regular col- umn by Woodrow Wyatt, billed, as ever, as The Voice of Reason. It was a routine example of his work: 12 grammatical errors, two anodyne attacks on Tony Blair and a single pat on the back for Michael Portillo.

The Lord Wyatt of Weeford, friend of the Queen Mother, stout monarchist, pro- ponent of privacy laws to curb press intru- sion, was, as has long been his habit, having his cake and eating it. He makes money for writing in the News of the World and headlines by attacking tabloid misde- meanours in the House of Lords. It is only one of the many anomalies in the topsy- turvy life of the man who has turned mav- erick behaviour into an art form and a lucrative career.

His track record is one of consistent inconsistency, quite apart from having been married four times. He disappointed his middle-class mother by joining the `dreadful Socialists'. After rising in the Labour Party, becoming the youngest member of government, he later became a back-bench dissident, and eventually an almost idolatrous supporter of Margaret Thatcher. In 1977 he wrote an article in the Daily Express, damning Labour and announcing he would vote Conservative in future. After Mrs Thatcher's fall he called John Major a 'remarkable statesman', before siding with the dismissed Chancel- lor Norman Lamont to the point of help- ing to fashion his resignation speech. But he says he has 'never become a Tory'. He appears to be the epitome of an establish- ment figure — dining with the great and the good, moving in the highest political circles, meeting the most important lead- ers of business — but affects to see himself as an outsider, saying, 'The establishment hates my guts.'

In that, at least, Wyatt may well be cor- rect. Certainly, there will be few tears this May among the members of the Jockey Club when he steps down, at long last, from the chairmanship of the Horserace Totalisator Board, the Tote. It is a quango post he has held tenaciously, in the face of great hostility, for almost 20 years. And it is a measure of this eccentric man's con- trariness that he has managed to provoke more controversy at the Tote than in set- ting out to do so in his newspaper columns.

One racing journalist recently referred to the Tote as Wyatt's 'personal ,fiefdom' and opened a book on his successor, who could well be named next month. The problem with Wyatt, according to many in the racing fraternity, is not so much what he has done (though there are plenty who believe he has not done enough) as his personality. As John Burrows of the Daily Telegraph put it, 'There are two schools of thought about his role in racing. On the one hand, there are those who believe he has used his talent for ingratiating himself with people in power to improve the posi- tion of both the sport and the Tote. On the other hand, are those who believe he has used his position at the Tote to improve his talent for ingratiating himself with people in power.'

Indeed, it is a tribute to Wyatt's political promiscuity that he first obtained the job, now worth £95,000 a year, and then main- tained himself in the chair. It was in 1976 that Roy Jenkins, then Labour home secre- tary, asked Wyatt to take over the Tote. He says that he refused at first, but 'I had always been amused by the racing world and thought the Tote could be an interest- ing office'. But his gratefulness to Jenkins is very clear indeed: 'I have never attacked Roy and never shall.' By the time the Tote chairmanship came up for renewal Wyatt's heroine was in power. According to Nicholas Budgen, Tory MP for Wolver- hampton South-West, one of Mrs Thatch- er's final acts 'in November 1990, in the last few hours of her time as prime minis- ter' was to reappoint him for three more years. By political standards, said Budgen, he deserved it for his party loyalty, but he asked, 'Does racing want more of their leaders appointed on this basis?'

John Oaksey, the Daily Telegraph's racing correspondent, was one of many who thought not. He argued two years ago that although Wyatt had 'introduced some posi- tive and helpful reforms in the early years „ . it is hard to see him as the right man to guide pool betting into a brave new age'. A report on the feasibility of privatising the Tote by Lloyds merchant bank, commis- sioned by the Home Office in 1989 and kept secret for 18 months, was critical of Wyatt's stewardship. His reaction, accord- ing to the Commons Home Affairs Com- mittee, 'bordered on the apoplectic'. Wyatt said its recommendations contained 'inex- cusable omissions, naivety, unwise propos- als and ignorance' and included 'highly offensive ... unjustified statements'. The MPs thought it wasn't as flawed as Wyatt appeared to think. They conceded that he was safeguarding the best interests of the Tote as he saw them, but added, 'We do not believe that it was wise for him to have done so in this way.' It didn't stop Kenneth Clarke, then home secretary and a top- table diner at Woodrow Wyatt's Tote annual lunch in March 1993, giving his host another two years as chairman.

Outside commentators have also expressed disquiet. Professor John Kay of the London Business School describes the Tote as 'a bizarre organisation . . . [its] status is an arcane legal matter (akin to that of the TSB before its flotation) and no one knows who owns it or its assets'. Set up some 66 years ago by a private member's bill, the Home Office continues to appoint the board even though the Government accepts that it doesn't own its assets. So the Tote under Wyatt has used the revenues it has derived from its monopoly to diversify into buying a chain of high-street betting- shops. As one incredulous Jockey Club member observed, 'The Tote makes up its own rules as it goes along.' As Professor Kay also points out, it is odd that the Tote, which is crying out to be privatised, has never even come under starter's orders in the stock market.

Another racing observer, angered that the Tote has not been built up to raise cash for the industry, said, 'At the moment, it's hardly more than a sinecure, allowing Wyatt to swan about with the Queen Mother.' So we are back to Wyatt's greatest skill, as a swaggering flatterer of those he considers his betters. The most unctuous of royal courtiers could not have worn out as many breeches as the fawning Wyatt.

Perhaps he learned it at his father's knee or, rather, at his head. The ailing prep school headmaster, who died in 1931 when Wyatt was only 13, required his son to stand behind his armchair and stroke his bald head for hours at a stretch as he read or did the crossword. He also stroked his father's back in bed and massaged his hand during church sermons. Though the young Wyatt clearly found this exhausting work, doing it well was the price of gaining a better existence. From then on, Wyatt has been renowned for stroking many an ego. There was the time in New York when he met Lord Beaverbrook, who had had fresh oysters flown from Canada. hate raw oysters,' Wyatt related in his autobiography Confessions of an Optimist. I covered them with pepper and rammed them down my throat.'

`Aren't you enjoying them?' asked Beaverbrook.

`Yes, they're marvellous,' replied Wyatt.

Wyatt, however, failed to excite the even richer Paul Getty, who remained 'miser- able, despite me trying my utmost flattery and jokes'. One who succumbed was Attlee. When Nye Bevan resigned from his government, Wyatt was quick to send the Labour, leader a note saying he was `moved' by the way he had coped with the crisis. He reward was to become the gov- ernment's youngest member as under-sec- retary of state for war. It was the opportunity to meet yet more famous peo- ple, such as General Montgomery, and the excuse for Wyatt later to boast of his con- nection.

He relates how Richard Dimbleby told Monty he disliked Wyatt being a socialist. According to Wyatt's own account, Monty snapped, 'Never mind his politics. He was a first-rate under-secretary of war.'

Nor did Wyatt mind the politics either. Though he loathed Harold Wilson's princi- ples, he has admitted he would have taken a job in his government eft is amazing how quickly the mind can adapt'), but wasn't offered one, and went off to cause trouble on the back-benches. It was during the great debate on Britain's east of Suez poli- cy that Wyatt, irritated by the required secrecy of a party meeting, 'published an accurate account of it in the Daily Mirror, openly breaking the rules'. When told he would be censured and disciplined he says, I laughed.' Yet he did not laugh when A.N. Wilson revealed the contents of a conversation with the Queen Mother at Wyatt's dinner table, as published in The Spectator in July 1990. 'Private conversations are private,' thundered Wyatt. It was 'a shabby trick'. Another day, another inconsistency. And however much he rails at The Spectator it doesn't stop him turning up to its annual garden party. Perhaps Wyatt's most surprising weak- ness is his writing. He once confessed that his early articles were 'stilted, full of facts and very dull'. Sub-editors who have had to deal with his work over the past 30 years would argue that it hasn't got much better since. Wyatt, needless to say, has a more exalted view of the power of his pen. He has come to believe that it was his columns in the Daily Mirror in the 1970s which tipped Ted Heath from power. shall be immodest,' he wrote. believe that my articles have influenced attitudes and voting patterns more than the total output of the grander and smaller circulation papers.' He left Mirror Group after 18 years to join the News of the World, 'a newspaper owned by my old friend Rupert Murdoch ... a democrat with a generous nature who wants people to be happy, as he is'. The Voice of Reason has proved an irascible presence at Wapping, intimidat- ing staff and rowing with editors, who have always been aware of his closeness to Mur- doch. One Sunday Times sub-editor who rang him with a query that obviously rat- tled him was told that she might be inter- ested to know that 'Rupert' happened to be staying with him at present.

Wyatt is probably right in thinking that he can always appeal to Murdoch over the heads of his dismayed editors, Though the official history has yet to be written, there is little doubt that Wyatt played a key role in helping Murdoch to set up Wapping. Quite what he did is a mystery. Executives in the know, or who pretend to be, will only whisper, `Rupert's always been grateful. Woodrow was, well, helpful.' Certainly, Wyatt's relations with the electricians' union which plugged Wapping in have been excellent since he fought alongside the former leader, Frank Chapple, to expose and then overturn a communist bal- lot-rigging scandal. Whatever criticisms are levelled now at Wyatt, that was his finest hour.

Or almost. Wyatt's other claim to fame is to have lured from Mrs Thatcher a gen- uinely funny remark. When many years ago they were on opposite sides of the political divide and had never met, they appeared on BBC radio's Any Questions? The panel were asked: What did you discuss at din- ner? Wyatt answered first, and as he was finishing Mrs Thatcher interrupted: 'May I make one thing quite clear, Mr Chairman? We weren't discussing very much at dinner. We were mostly listening to Mr Woodrow Wyatt.'

So have we all been, for far too long.

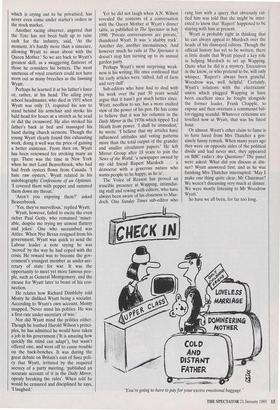

'You're going to have to pay for your excess emotional baggage.'

Previous page

Previous page