Exhibitions

Nicolas Poussin (Royal Academy, till 9 April)

Deepening appreciation

Giles Auty

ill the previous exhibition at the Royal Academy herald an interesting new trend? In the winter issue of that institu- tion's own high-circulation magazine, British art critics were given a pretty poor press themselves for not showing sufficient enthusiasm for the lately-concluded Glory of Venice. May not the most outspoken but also the most independent body of critics in the world make up its own mind any longer? The bossiness and self-regard of present-day art administrators knows no bounds; nobody seems to be permitted any view which conflicts with theirs — yet this latter is, as often as not, as misguided as it could be. So to Poussin. Are the views of the British art press likely to provoke a fur- ther fusillade?

Happily enthusiasm for Poussin has hardly ever been less in this country than in the artist's native France. We beastly Brits may not care overmuch for 18th-century Venetian Baroque yet we yield to none in our admiration for French artists as various as Poussin, Claude and Rodin. The chance to look at Poussin in depth is both rare and welcome. The master is represented by more than 90 paintings which grow both in accomplishment and mystery as the years pass by. Yet high competence and rigour were there from the outset. If these sound unappealing qualities, they form a secure basis, nonetheless, for the full majesty to come. The Royal Academy intends to explain each work to modern audiences by means of a short, adjacent text. Since few may know much today about the sources of subjects such as 'Achilles amidst the Daughters of Lycomedes' or even Tancred and Erminia' such an initiative is welcome. Yet one cannot help wondering how long it will be before events from the New as well as Old Testaments may require similar explaining: The Virgin was a name given sometimes to the mother of Jesus. . . '

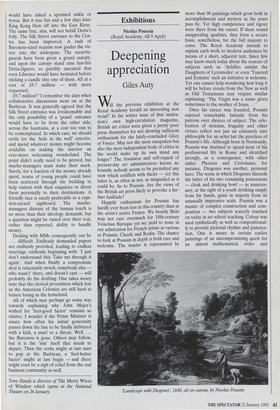

Once his career was founded, Poussin enjoyed remarkable latitude from his patrons over choices of subject. The cele- bration of stoicism, frugality and other virtues reflect not just an extremely rare philosophy for an artist but the practices of Poussin's life. Although born in Normandy, Poussin was destined to spend most of his professional life in Rome and identified strongly, as a consequence, with other exiles: Phocion and Coriolanus, for instance. Diogenes was another, personal hero. The scene in which Diogenes discards the latter of his two remaining possessions — cloak and drinking bowl — as unneces- sary, at the sight of a youth drinking simply from his hands, gains in majesty from its unusually impressive scale. Poussin was a master of complex construction and com- position — two subjects scarcely touched on today in art school teaching. Colour was used symbolically as well as compositional- ly to provide pictorial rhythm and punctua- tion. One is aware in certain earlier paintings of an uncompromising quest for an almost mathematical order and Eandscape with Diogenes, 1648, oil on canvas, by Nicolas Poussin precision. Broadly, the beauties of a unify- ing tonality came later in Poussin's work yet compositional experiments and research also contributed much in the achievement of his final harmonies.

Until the artist's last phases, there is no painting in the present exhibition that thrills me more than one drawn from 'The Second Set of Seven Sacraments', namely the wonderful 'Baptism' of 1646. Both sets of sacraments are shown complete at the Royal Academy. The landscape and figures of this particular 'Baptism' have a credibili- ty and atmosphere that is not always found elsewhere. The secret behind this is a beau- tiful, unifying tone. Compare this true mas- terpiece with Poussin's 'The Continence of Scipio' from only six years earlier and you will find the latter looks relatively wooden and unconvincing, its distribution of prima- ry colours too sudden and arbitrary, its lighting altogether too harsh, artificial and inconsistent. Indeed, in the use of chiaroscuro — strong contrasts of dark and light — and also in his choice and use of believable human models, I would argue that Caravaggio, who spent much of his short life also in Rome and was exactly 25 years Poussin's senior, was comfortably his superior in achievement. The two men could hardly have been more unlike in their temperaments and behaviour, yet the rigid rationality once typical of Poussin abated in his last years to be replaced by an almost mystical lyricism.

I do not feel I need seek the permission of the Royal Academy's controllers to say that I enjoy this phase' of Poussin more than some of what went before. There were elements in Poussin which were occasional- ly over-didactic and arid, yet the creator of the final 'Four Seasons' earned his unquali- fied right of entry to art's pantheon. Artists of genius as distinct as , Gericault, Turner and Cezanne acknowledged the supreme force of Poussin's final flowerings. A pro- longed visit to the Royal Academy in the wintry weeks ahead should enable you to do the same.

Previous page

Previous page