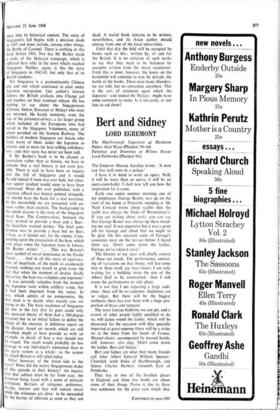

Sinister Twilight : The Fall and Rise Again of Singapore

Noel Barber (Collins 30s)

Loser's game

C. NORTHCOTE PARKINSON

Mr Noel Barber is a journalist of distinction, for many years chief foreign correspondent of

the. Daily Mail and the author more recently it of more, than a dozen books on current affairs, politics and travel. This present work is a fi description of the fall of Singapore, beginning on 7 December 1941, and concluding with a 1: final chapter on the horrors of internment fi and the end of the war. His readable and lively ti

narrative is based almost entirely on British

sources, published or unpublished, some here tl used for the first time. The bibliography is far cl from complete but it comprises about sixty e titles, two of them translated from the b Japanese. Although the author would seem to d

have no specialised knowledge of south-east tf

Asia, he tells a convincing tale of endurance b and revival and one which the future historian cannot ignore; among his more important dis- st coveries are the unpublished reports written by Ivan Simson, Brigadier an on General Perce- val's staff, shedding new light on Singapbre's 0;

lack of defences. c( But, while the merits of this narrative are la

undeniable, its limitations have to be realised.

The author has made no attempt to fit his b, story into its historical context. The story of Singapore's fall begins with a decision made in 1905 and must include, among other things, the Battle of Coronel. There is nothing in this book before 1941. Nor has Mr Barber made a study of the Malayan campaign, which is reflected here only in the news which reached Singapore. Neither, again, is this the story of Singapore in 1942-45, but only that of its British residents.

Yet Singapore is a predominantly Chinese city and one which continued to exist under Japanese occupation. Our author's interest follows the British civilians into Changi jail and touches on their eventual release. He has nothing to say about the Singaporeans (Chinese, Indian, Eurasian or Malay) who were not interned. He barely mentions, even, the fate of the prisoners-of-war, a far larger group which included all the Europeans who had served in the Singapore Volunteers, many of whom perished on the Siamese Railway. The builders of modern Singapore are Asians who lived, many of them, under the Japanese as citizens and as more (or less) willing collabora- tors: and their story has never yet been told.

If Mr Barber's book is to be classed as journalism rather than as history, we have to concede that a real history is not even pos- sible. There is said to have been an inquiry into the fall of Singapore and it would be odd indeed if none was ever held, but what- ever report resulted would seem to have been suppressed. Were this ever published, with a Japanese official war history printed alongside, we should have the basis for a real narrative. In the meanwhile we are presented with ex- cuses rather than analysis. The background to the whole disaster is the story of the Singapore naval base. The Conservatives, between the wars, wanted to provide a base and a fleet: the Socialists wanted neither. The final com- promise was to provide a base but no fleet; a base, as it turned out, for the enemy. Com- menting upon the evacuation of the base, which took place when the Japanese were in Johore, Mr Barber writes: `. . . This was Britain's great symbol of naval dominance in the Pacific Ocean . . . And in all this story of equivoca- tion, of ineptitude, of the myth so assiduously fostered, nothing can match in grim irony the fact that when the moment of destiny finally did arrive, the base was valueless and impotent.'

It was certainly valueless from the moment the Japanese were within artillery range, but it had been impotent from the outset. In war, which admits of no compromise, the first need is to decide what exactly you are trying to do. The basic weakness of Singapore lay not in the fact that its guns could only fire seaward (many of them had a 360-degree traverse) but in an initial failure to define the object of the exercise. A definitive report on the disaster, based on records which are still classified, might at least provide us with an example, in detail, of how a war should not be waged. The result would probably do less damage to any individual's reputation than to the party system as a whole: to the system by which Britain is still ruled today.

What, however, of the Asian side to the story? What did the native Singaporeans make of this episode in their history? An inquiry into that subject must be far from easy, the historian being faced with a scene of intricate confusion. Barriers of reticence, politeness, loyalty, interest and fear will remain intact while the witnesses are alive: to be succeeded by the barrier of oblivion as soon as they are

dead. A useful book remains to be written, nevertheless, and its Asian author should emerge from one of the local universities.

Until that day the field will be occupied by books such as this: written by, of and for the British. It is no criticism of such works to say that they need to be balanced by accounts written from the Asian standpoint. Until this is done, however, the losers on the battlefield will continue to win, by default, the battle of the books. There were many blunders, we are told, but no cowardice anywhere. This is the sort of statement upon which the Japanese—and indeed the Malays—might have sothe comment to make. Is it too early, or too late, to ask them?

Previous page

Previous page