Exhibitions

Otto Dix (Tate Gallery, till 17 May)

Real misgivings

Giles Auty

The Tate's free broadsheet explaining the current exhibition starts very confident- ly: 'Otto Dix (1891-1969) is the foremost German realist of the 20th century. . . '. No beating about the bush here: someone, somewhere is confident both in their defi- nition and judgment. However, such cer- tainty — no matter how misplaced— was hardly shared by the person responsible for the written texts which punctuate the dis- plays of Dix's work on the gallery walls. The first three of these manage to contra- dict each other and include the notable apercu that the influence of Nietzsche on Dix 'gave him a burning desire to show things as they really were and not as super- ficial appearances suggested'. Clearly, the question of realism in visual art is a knotty one and seemingly confuses even those who would instruct the public in its mean- ing. In any reasonable use of the term, Dix was not a realist at all, so it seems fairly unwise to debate his precise status in the hierarchy of German 20th-century realists.

Dix was an uneven artist in terms both of quality and style. In fact, the most consis- tent element in his art was that he was sel- dom if ever content to let appearances, superficial or otherwise, speak for them- selves. Generally Dix exaggerated, drama- tised or caricatured his human subject matter in a way that is the reverse of docu- mentary. In short, we are never presented with 'appearances' and invited to make up our own minds. We are battered instead by Dix's tendentious satire and symbolism. The artist reacted to the horrors of the first world war and the nervous decadence of its aftermath with violent and often gruesome caricature as the principal weapon in his armoury. He flirted briefly with Expres- sionism, Futurism and Dada before becom- ing sceptical about the new languages of art and seeking salvation in the well-proven expressive powers of the old. But I pre- sume the artists to whom Dix turned — Altdorfer, Cranach, Griinewald — would hardly be described as realists even by the Tate Gallery's scholarly staff.

If realism in 20th-century Germany is to be a subject for discussion, the Tate's experts might do well to look at genuine exemplars such as Erich Wolfsfeld (1885-1956), who lived in England from 1939 to 1956 and was one of the more accomplished etchers of this century, his pupil Lotte Laserstein (b. 1898), or Gott- fried Meyer (b. 1911). When Laserstein's work was seen first in Britain in October 1987 it was an absolute revelation. Foreign and British provincial museums bought paintings, but not the Tate, who were offered wonderful examples then and sub- sequently. Neither does that institution own a single etching by Wolfsfeld. To buy such works requires the judgment of the eye, an attribute found all too seldom among present-day art historians.

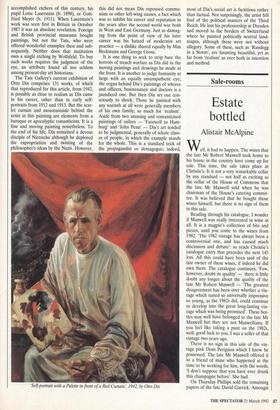

The Tate Gallery's current exhibition of Otto Dix comprises 131 works, of which that reproduced for this article, from 1942, is possible as close to realism as Dix came in his career, other than in early self- portraits from 1912 and 1913. But the scar- let curtain and mountainside behind the artist in this painting are elements from a baroque or apocalyptic romanticism. It is a fine and moving painting nonetheless. To the end of his life, Dix remained a devout disciple of Nietzsche although he deplored the expropriation and twisting of the philosopher's ideas by the Nazis. However, this did not mean Dix espoused commu- nism or other left-wing causes, a fact which was to inhibit his career and reputation in the years after the second world war both in West and East Germany. Just as damag- ing from the point of view of his later career was his hatred of modernist art practice — a dislike shared equally by Max Beckmann and George Grosz.

It is one thing to seek to strip bare the horrors of trench warfare as Dix did in the moving paintings and drawings he made at the front. It is another to judge humanity at large with an equally unsympathetic eye; the organ behind Dix's paintings of whores and officers, businessmen and doctors is a jaundiced one. But then Dix set out con- sciously to shock. Those he painted with any warmth at all were generally members of his own family; so much for 'realism'. Aside from two amusing and romanticised paintings of sailors — 'Farewell to Ham- burg' and 'John Penn' — Dix's art tended to be judgmental, generally of whole class- es of people, in which the example stands for the whole. This is a standard trick of the propagandist or demagogue; indeed, `Self-portrait with a Palette in front of a Red Curtain, 1942, by Otto Dix most of Dix's social art is factitious rather than factual. Not surprisingly, the artist fell foul of the political masters of the Third Reich. He lost his professorship at Dresden and moved to the borders of Switzerland where he painted politically neutral land- scapes, although these were not without allegory. Some of these, such as `Randegg in a Storm', are haunting beautiful, yet as far from 'realism' as ever both in intention and method.

Previous page

Previous page