. . . very much unlike what people write

Peter Quennell

BYRON'S TRAVELS by Allan Massie Sidgwick & Jackson, £15, pp.221 `A man must travel, and turmoil, or there is no existence', Byron in 1822 told his comparatively unadventurous friend Tom Moore. 'The great object of life is sensation,' he had declared a year earlier; and that object he had pursued, sometimes with self-destructive zeal, by regularly plunging into fresh experiences and, as Odysseus had done, surveying 'the cities and the minds of men'. He was always in search of knowledge; 'Anything', he wrote, 'that confirms or extends one's observations on life and character delights me, even when I don't know people.' I've taught me other tongues and in strange eyes / have made me not a stranger' was a claim that he had certainly established.

Nature, on the other hand, though it often moved and excited him, he found a little less absorbing; and although he pro- duced a splendidly Turneresque vision of an alpine thunderstorm and remembered a radiant sunset and its slow-changing col- ours, while day 'died like a dolphin' on an Italian mountain slope, as a rule he prefer- red to study mankind. In the letters and poems he sent home from Venice there are not many tributes to works of art; and what most enchanted him were the Venetians themselves, the beauty and oddity of their women and the outlandish patois they spoke — 'very naïve, and soft, and pecul- iar, though not at all classical' — and the fact that a baker's wife's quarrelsome conversation might often include refer- ences to the Republic's former victories.

Venice had become 'the greenest island of his imagination'; and there, once he had embarked on Don Juan, Allan Massie points out in his agreeably discursive book, as a poet he would come of age. This was due, however, not to his amorous rela- tionships with Marianna Segati, and her chief successor Margarita Cogni, who made his development 'easy and pleasur- able', but to a rapid broadening of his outlook. The sense of deep guilt — 'the nightmare of his own delinquencies' that had haunted him since he left England - had at last been cast off. He now meant to amuse himself and entertain a disapprov- ing world. In Don Juan, undoubtedly his masterpiece, he looked back on his stormy passage through life and drew his imagina- tive conclusions. Human existence was frequently comic as well as tragic and dramatic. Few poems since the age of Pope Introduce so many sharply pointed jokes and may arouse such ribald laughter.

It is also stocked with vivid portraits — Lambro, the ferocious buccaneer — 'the mildest mannered man that ever scuttled ship or cut a throat'; the Sultan himself 'a monarch of solemn port, shawled to the 'lose and bearded to the eyes'; Duc16, the lovely odalisque, and much later, when Juan reaches London, the chaste beauty Lady Adeline Amundeville and her impos- ing consort Lord Henry, that 'cold, good, honourable man', the type of high-minded but cold-blooded British Tory.

On his various travels, Byron had made many other valuable acquaintances; during his first Grand Tour, for example, he encountered Ali Pasha, the savage tyrant of Yanina, who welcomed him with flatter- ing 'squeezes and speeches', and said that he must be of noble birth because his ears were so small! Stendhal, too, during a subsequent stage of his odyssey, he would encounter at an Italian opera house. The future novelist, like himself, was a keen admirer of Napoleon. They enjoyed dis- cussing the emperor's genius; and Stendhal was greatly impressed by Childe Harold's youthful good looks. He had expected, no doubt, a romantic misanthrope. But Lord Byron, he found, was a charming and elegant young man, and might once have been the 'original of Lovelace'.

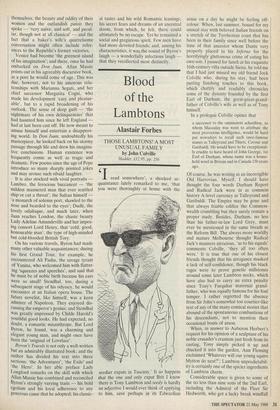

Byron'k Travels is not only a well-written but an admirably illustrated book; and the author has divided his text into three sections: 'the Adventurer', 'the Exile' and `the Hero'. In her able preface Lady Longford remarks on the skill with which Allan Massie has combined and reconciled byron's strongly varying traits — his bold egotism and his loyal adherence to any generous cause that he adopted; his classic- al tastes and his wild Romantic leanings; his secret fears and dreams of an ancestral doom, from which, he felt, there could ultimately be no escape. Yet he remained a social and gregarious spirit. Few men have had more devoted friends; and, among his characteristics, it was_the sound of Byron's laugh — a wonderfully infectious laugh that they recollected most distinctly.

Previous page

Previous page