Exhibitions 3

The fine art of comedy

Nicholas Garland

he V & A is celebrating the New Yorker's 60th anniversary with an exhibi- tion of over 100 cover paintings and cartoons. The show itself is a smaller version of one of those 25-year albums of their own drawings that the New Yorker produces now and then, except that here you can walk around among the originals and therefore get much closer to the artists' hands and eyes — seeing as it were the nuts and bolts, the corrected errors and late adjustments.

If you are lucky you'll be among a relaxed, good-natured crowd and hear bursts of laughter and a buzz of animated conversation that is most unusual, and very welcome, in an art gallery. You will notice certain pictures further down the line tickling everyone who stops in front of them, and see strangers smiling at each other's amusement. It is not unlike being at a successful comedy in the theatre, with the play borne along on the delighted response of the audience.

Among many pleasures, my only mild disappointment was that the exhibition was not twice as large, which, incidentally, would have forced it out of the overflow corridor and into the proper full-sized gallery it deserves. I have an uncomfort- able feeling that this venue could in part be a manifestation of the false artistic pecking order so widely accepted in this country, in which comic art is regarded as the lowly, rather vulgar relation of the lofty princes of fine art. The fact is there are true and serious artists working in the comic mode. In the V & A's show there is a Peter Arno drawing captioned 'Valerie won't be around for several days. She backed into a sizzling platter'. Just study the superb figure drawing of the showgirls and their twinkling high-heeled shoes. You don't get drawing much better than that anywhere — cry your eyes out, Allen Jones. In fact Peter Arno is probably the greatest draughtsman the New Yorker has nurtured, as well as one of the funniest. Rea Irvin, Charles Addams and the less well-known Mary Petty are in the same league, but the other towering comic genius is James Thurber. At first glance their styles could not be more different. Andy White once came across Thurber trying to add weight and depth to a drawing with laborious cross-hatching. 'Good God!' he said, 'don't do that! If you ever became good you'd be mediocre.'

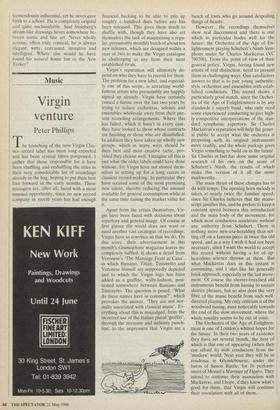

But elsewhere there is an overlap in the work of these two men. Dorothy Parker puts it perfectly in her preface to the Thurber collection, A Seal in the Bedroom. (That immortal drawing is on view, by the way.) What she identifies is actually part of the New Yorker genre. 'Thurber,' she says, 'deals solely in culminations. Beneath his pictures he sets only the final line. You may figure for yourself, and good luck to you, what under heaven could have gone before, that his sombre citizens find them- selves in such remarkable situations . . . he gives you a glimpse of the startling present and leaves you to construct the astonishing past.' The perfect example is 0. Soglow's polar bear paddling contentedly about in a kayak, the first cartoon to make me laugh out loud at the exhibition.

George Price, the King of Kitsch, uses this elusive quality with great brilliance. One of his drawings is so poignant as to be almost unbearable. A middle-aged man is returning home from work while, hidden from view, his decrepit wife, cocktail poised on tray, is waiting for him hideously and glumly dolled up in Bunny's gear. The ghastly short story required to explain, let alone resolve the imminent confrontation produces an instantaneous laugh and shud- der.

Black humour runs throughout the New Yorker oeuvre, with the mighty Charles Addams its greatest exponent. He is well represented here. Included is his unforget- table skier whose tracks pass so unmistak- ably either side of a solid pine. The mind simply blows a fuse at this point: no earthbound saga can account for this start- ling present or impossible past.

Direct political comment or social critic- ism are not themes that the editors have ever emphasised heavily, but they emerge with surprising vigour from time to time. There is considerable edge to Mary Petty's 1930 drawing of three languid students, dozily drinking an evening away. One is saying with comical but exasperating earnestness, 'You know what we're getting into, don't you? A million men are idle right now in this country.'

But most of the exhibits belong to another category altogether, theplain old wise-cracking one-liner joke. Everyone will have their favourites: mine are the Frenchman Sempe, Cobean, Kovarsky and Richard Taylor of the heavy eyelids. A typically lovely Kovarsky shows two ship- wrecked mariners on a raft about to be swamped by Hokusai's great over-arching claw of a wave. 'We're in Japanese waters, that's for sure.' Cobean mostly does with- out a caption.

There is one more artist whose work must be singled out. He has been

'It's ()girth's boat all right, but it doesn't look like Oglub' — 0. Soglow's cartoon first published in the New Yorker in 1953. tremendously influential, yet he never gave birth to a school. He is completely original and quite unclassifiable. Saul Steinberg's dream-like drawings hover somewhere be- tween comic and fine art. Never wholly scrious, often truly comical, he is always elegant, witty, restrained, inventive and intelligent. Where else would he have found his natural home but in the New Yorker?

Previous page

Previous page