Exhibitions

Avigdor Arikha: Works 1992-93 (Marlborough Fine Art, till 4 June) The Art of Vietnam (Roy Miles Gallery, till 24 May)

Economy of means

Giles Auty

Aikha is an odd phenomenon: a man who writes and speaks with great intelli- gence about figurative painting but who makes such art rather less convincingly and almost crudely at times. Before I knew anything about his background, I imagined

he was a writer who had taken up painting seriously at the age of 30 or thereabouts. I was wrong.

Until that age Arikha was an abstract artist. His subsequent art — he is 65 now — seems to me like a valiant effort to retrieve what must be seen largely as wasted years in the light of his present practice. Arikha has become a very successful artist but reputations and bank balances are not really the province of this column.

The present exhibition at Marlborough Fine Art (6 Albemarle Street, W1) brings us a selection of Arikha's paintings, drawings and etchings of recent vintage. The etchings are the most impressive aspect of his art, evoking memories at times of Eric Wolfsfeld (1884-1956) who was forced to leave Germany in 1939 and who spent much of the rest of his life in England.

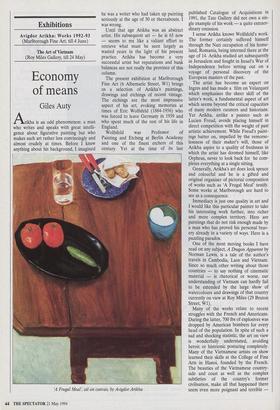

Wolfsfeld was Professor of Painting and Etching at Berlin Academy and one of the finest etchers of this century. Yet at the time of its last 'A Frugal Meal', oil on canvas, by Avigdor Arikha published Catalogue of Acquisitions in 1991, the Tate Gallery did not own a sin- gle example of his work — a quite extraor- dinary omission.

I sense Arikha knows Wolfsfeld's work. The former certainly suffered himself through the Nazi occupation of his home- land, Romania, being interned there at the age of 14. Arikha studied art subsequently in Jerusalem and fought in Israel's War of Independence before setting out on a voyage of personal discovery of the European masters of the past.

The artist has become an expert on Ingres and has made a film on Velazquez which emphasises the sheer skill of the latter's work, a fundamental aspect of art which seems beyond the critical capacities of many modern curators and historians. Yet Arikha, unlike a painter such as Lucien Freud, avoids placing himself in direct competition with the weight of past artistic achievement. While Freud's paint- ings batter on, impelled by the remorse- lessness of their maker's will, those of Arikha aspire to a quality of freshness in which the artist has doomed himself, like Orpheus, never to look back for he com- pletes everything at a single sitting.

Generally, Arikha's art does look spruce and colourful and he is a gifted and original organiser of pictorial composition of works such as 'A Frugal Meal' testify. Some works at Marlborough are hard to see as a consequence.

Immediacy is just one quality in art and I would like this particular painter to take his interesting work further, into richer and more complex territory. Here are paintings that do not risk enough made by a man who has proved his personal brav- ery already in a variety of ways. Here is a puzzling paradox.

One of the most moving books I have read on any subject, A Dragon Apparent by Norman Lewis, is a tale of the author's travels in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Since so much other writing about those countries — to say nothing of cinematic material — is rhetorical or worse, our understanding of Vietnam can hardly fail to be extended by the large show of watercolours and drawings of that country currently on view at Roy Miles (29 Bruton Street, W1).

Many of the works relate to recent struggles with the French and Americans. During the latter, 700 lbs of explosives was dropped by American bombers for every head of the population. In spite of such a sad and shocking statistic, the art on view is wonderfully understated, avoiding heroic or histrionic posturing completely. Many of the Vietnamese artists on show learned their skills at the College of Fine Arts in Hanoi, founded by the French. The beauties of the Vietnamese country- side and coast as well as the complex subtleties of the country's former civilisation, make all that happened there seem even more poignant and terrible — just as in Cambodia.

A strong sense of stoicism infuses many of the drawings but then many of the small men and women who are depicted man- ning equally puny-looking anti-aircraft guns were peasants long accustomed to privation and woe.

A drawing showing a captured American pilot emphasises the physical disparities of different peoples. We know already of immense numbers of photographs which chronicle the anguish as well as beauties of Vietnam but drawings made by artists working patiently on the spot add a partic- ularly moving note to the archive.

We may reflect here how fortunate it was for posterity that so many artists of previ- ous decades were still taught to draw.

Previous page

Previous page