Theatre

Falling Over England (Greenwich)

Elgaes Rondo (Barbican Pit) No Big Deal

(Orange Tree, Richmond)

The generation game

Sheridan Morley

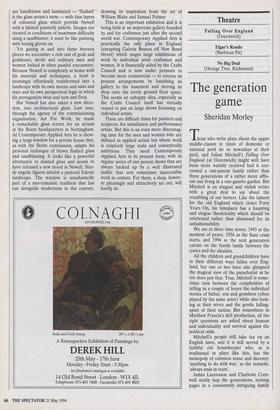

hose who write plays about the upper middle-classes in times of domestic or national peril do so nowadays at their peril, and Julian Mitchell's Falling Over England (at Greenwich) might well have been more warmly received had it con- cerned a one-parent family rather than three generations of a rather more afflu- ent one living in a one-gazebo garden. But Mitchell is an elegant and stylish writer with a great deal to say about the crumbling of our betters. Like the lament for the old England which closes Forty Years On, his timepiece has a haunting and elegiac theatricality which should be celebrated rather than dismissed for its unfashionability.

We are in three time zones: 1945 at the moment of peace, 1956 as the Suez crisis starts, and 1994 as the next generation carries on the family battle between the cynics and the idealists.

All the children and grandchildren have in their different ways fallen over Eng- land, but one or two have also glimpsed the magical view of the parachutist as he too does just that. True, Mitchell is some- times torn between the complexities of telling in a couple of hours the individual stories of father, son and grandson (often played by the same actor) while also look- ing at their wives and the gentle falling- apart of their nation. But somewhere in Matthew Francis's deft production, all the right questions are asked about honour and individuality and survival against the political odds.

Mitchell's people still take tea on an English lawn, and it is still served by a faithful old housekeeper who, as is traditional in plays like this, has the monopoly of common sense and decency: 'anything to do with war,' as she remarks, 'always ends in tears'.

James Laurenson and Charlotte Corn- well neatly hop the generations, turning pages in a consistently intriguing family

album even as the skeletons crash out of the closets.

Though it is not exactly another Amadeus, Elgar's Rondo (in the Barbican Pit) also looks at a composer in crisis and the ghosts who come back to haunt him. In a week when English country gardens have been all over our stages, this one is by the Thames in Berkshire, where the great composer has gone to stay with friends after the disastrous reception of his Sec- ond Symphony. The dramatist David Pow- nall (here as in his Master Class about Stalin and Shostakovich and Prokofiev) is clearly fascinated by the power-play between composers and their political masters: in 1914 we therefore get King George v and the massed bands of his Guards coming to rouse Elgar from wartime lethargy and get him back to the land of hope and glory.

In Alec McCowen's tortured and superb performance we are given all sides of Elgar: the jingo-patriot turned pacifist, the good husband lusting after a potential mistress, the prolific composer who suddenly cannot write a note. Pownall raises the questions, and wisely doesn't hope for too many answers: if the war had not come, would Elgar's muse anyway have either changed him or deserted him? Is it better to be remembered for patriotic marching songs than not at all? Was the Rondo really any better for being inacces- sible to its first audiences? What, if any- thing, is the duty of a composer in war?

To debate these issues, Pownall also gives us Bernard Shaw (in a feisty performance from James Hayes) and, back from the dead, Elgar's first agent (John Carlisle) as well as his long-suffering wife (Sheila Ballantine). All in Di Trevis's agile production have some sort of vested interest in getting Elgar out of his creative crisis, an achievement in the end of a young Jesuit priest who just happens, in more ways than one, to be camping out in the garden.

In a week when the press on both sides of the Atlantic has, and not before time, begun to wonder whether it is really a good thing to have creative counsellors rooting about in lost sexual memory as though it were a boot cupboard full of excitingly forgotten cardboard boxes, Rod Beacham's No Big Deal (at the Orange Tree in Richmond) could hardly be more topical.

Its star is Fay (Joanna Van Gyseghem in a suitably over-the-top appearance), an American sex-lecturer come to flog a self- help manual around England but also unfortunately to stay with some old English friends into whose already uneasy domestic life she cheerfully brings further torment by leaping into bed with a hitherto closeted wife.

Kaufman and Hart would have called this The Woman Who Came to Dinner: moved to the London suburbs. It is only intermittently entertaining.

Previous page

Previous page