ARTS

Design

Stylish is the North

Tanya Harrod admires the thoughtful creativity of the Finns 0 ne of the finest surviving Arts and Crafts houses in existence is perched above a Finnish lake outside Helsinki. Hvittrask was built in 1902 by the youthful Eliel Saarinen — later architect and principal of Cranbrook Academy in the United States — in collaboration with fellow students Herman Gesellius and Armas Lindgren. William Morris would have appreciated this glorious Finnish Kunstgesamtwerk he was greatly indebted to the ancient Nordic culture he found virtually intact in Iceland. And Saarinen read Morris eagerly but, like the romantic nationalists of Hun- gary and Russia, he found much in his own culture to inspire him. The Finnish variant of Arts and Crafts makes the British move- ment seem positively genteel. Hvittrask's massive pine log and granite structure draws on vernacular Karelian farmhouse architecture, with forms dictat- ed by the extremes of climate and by avail- able natural materials. Each room houses a great tiled stove and the upper rooms have low, curved ceilings rich with patterns intended to reflect Finno-Ungric orna- ment. Traditional knotted ryify rugs are dramatically arranged, hanging from the wall, flowing over a sofa and then extend- ing across the floor, creating a throne-like effect of barbaric splendour. Hvittrask is a building that as much as anything sets out to create a sense of national identity in the face of centuries of Swedish domination and, during the 19th century, a humiliating position as a duchy ruled by a Russian governor-general. Russia's cultural influ- ence is most clearly seen in the centre of Helsinki, where the neo-classical squares laid out by Carl Ludwig Engel are startling- ly reminiscent of St Petersburg.

It is always dangerous to generalise about the design characteristics of a partic- ular country but, despite her complex histo- ry, Finland appears to have a strong visual identity which other countries might envy. One of the prime exponents of Finnish regionalism is Tapio Periainen, the director of Finland's equivalent of the Design Council, Design Forum. His idiosyncratic book Soul in Design: Finland as an Example — half a straight survey of Finnish product design, half poetic musings on national character — is not popular with young designers who do not want to be cate- gorised as specifically Finnish. But Periai- nen seems able to identify a distinctive aesthetic that is above all dictated by Fin- land's harsh natural environment.

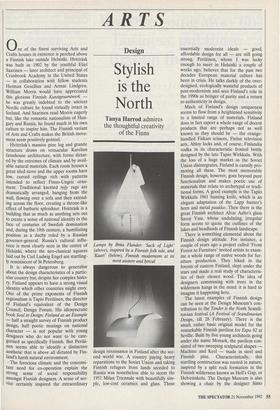

The ferocious climate and the concomi- tant need for co-operation explain the strong sense of social responsibility amongst Finnish designers. A sense of ser- vice certainly inspired the extraordinary Lamps by Brita Flander:• 'Sack of Light' (above), inspired by a Finnish folk tale, and `Kaari' (below), Finnish modernism at its most austere and lyrical design renaissance in Finland after the sec- ond world war. A country paying heavy reparations to the Soviet Union and taking Finnish refugees from lands seceded to Russia was nonetheless able to storm the 1951 Milan Triennale with beautifully sim- ple, low-cost ceramics and glass. These essentially modernist ideals — good, affordable design for all — are still going strong. Periainen, whom I was lucky enough to meet in Helsinki a couple of weeks ago, believes that for the past two decades European material culture has been in crisis. He talks darkly of the over- designed, ecologically wasteful products of post-modernism and sees Finland's role in the 1990s as bringer of purity and a return to authenticity in design.

Much of Finland's design uniqueness seems to flow from a heightened sensitivity to a limited range of materials. Finland does in fact export a whole range of decent products that are perhaps not as well known as they should be — the orange- handled Fiskars scissors, Finlux television sets, Abloy locks and, of course, Finlandia vodka in its characteristic frosted bottle designed by the late Tapio Wirkkala. With the loss of a huge market as the Soviet Union disintegrates, Finland is cannily pro- moting all these. The most memorable Finnish design, however, goes beyond pure functionalism and makes poetic use of materials that relate to archetypal or tradi- tional forms. A good example is the Tapio Wirkkala 1961 hunting knife, which is an elegant adaptation of the Lapp hunter's horn and metal puukko. Then there is the great Finnish architect Alvar Aalto's glass Savoy Vase, whose undulating, irregular form seems to quote the outlines of the lakes and headlands of Finnish landscape.

There is something elemental about the Finnish design attitude. For instance, a couple of years ago a project called 'From Forest to Furniture' invited artists to exam- ine a whole range of native woods for fur- niture production. They hiked in the forests of eastern Finland, slept under the stars and made a real study of characteris- tics of their chosen wood. The idea of designers communing with trees in the wilderness hangs in the mind: it is hard to imagine it happening here.

The latest examples of Finnish design can be seen at the Design Museum's con- tribution to the Tender is the North Scandi- navian festival (A Festival of Scandinavian Design, till 28 February). There is the small, rather basic original model for the remarkable Finnish pavilion for Expo 92 at Seville. Built by five young architects going under the name Monark, the pavilion con- sisted of two sweeping sculptural shapes Machine and Keel — made in steel and Finnish pine. Characteristically, this startling construction was rooted in nature, inspired by a split rock formation in the Finnish wilderness known as Hell's Gap, or Helvetinkolu. The Design Museum is also showing a chair by the designer Simo Heikkila which, though not the best exam- ple of his work, gives an idea of the contin- uing creative experimentation with lamin- ated wood pioneered by Alvar Aalto in the 1930s. Periainen is romantic about Simo Heikkila, arguing that he comes of peasant stock and that his ideas 'gush forth from his closeness to the earth, from nature and from the basic principles of peasant cul- ture'. Finland is a country with enough wilderness and folk culture to make Periaj- nen's cranky-sounding theories about a Finnish soul seem credible. In the late 19th century the Finnish epic the Kavela was studied by a whole generation of architects, painters and composers. A rather more homely story of foolish peasants building a windowless house and then trying to bring light into the house in a bag inspired Brita Flander's 'Sack of Light' lamp. A title like that — readily understood by one and all in Finland — only works in a cohesive, shared culture. The new lighting by Flander at the Design Museum draws on rather different sources: Finnish modernism at its most austere and the lyrical Finnish way with glass. Glass design has a powerful visual resonance in a country that turns to ice for such long periods each year.

Stefan Lindfors is probably the best- known young Finnish designer, and his work has a rather different, less purist feel to it. Lindfors, a wild, attractive figure who has created some elegant deconstructivist furniture, made his youthful name with his carapace-inspired Scaragoo lamp currently on show at the Design Museum. Nothing about Lindfors's eclectic style seems typi- cally Finnish and he has freelance contracts for lighting and furniture all over Europe. But to his credit he has remained in Helsinki, finding it as good a window on the world as any capital city. He is also a sculptor who last year mounted an ambi- tious show at the Amos Anderson Gallery in Helsinki. The catalogue, mostly written by Lindfors, is a remarkable document in its own right that on closer examination takes us right back to the classic Finnish themes — nature, the Finnish folk past and social idealism.

The Design Museum's three current exhibitions help us trace the course of Finnish design this century in the context of her Nordic neighbours. But I suspect to get at the secret of the Finnish soul and understand fully the integrity of their design aesthetic it is necessary to head to Finland's wilderness of lakes and forests during the extraordinary nightless summer and to experience the Finnish winter. Per- 'amen explains that until recently doors in country places were left unlocked so that no traveller would be left to freeze in the numbing cold. That takes us to the heart of the matter: the abstract purity of wood and granite, ice and snow informs Finnish design. So too does the need to work co- operatively. Social responsibility as much as individual expression underlines the thoughtful creativity of the Finns.

Previous page

Previous page