Exhibitions

Edvard Munch: the Frieze of Life (National Gallery, till 7 February) Border Crossings: 14 Scandinavian Artists (Barbican Art Gallery, till 7 February) Frans Widerberg (Barbican Concourse Gallery, till 15 December)

Nordic neuroses

Giles Auty

The exhibition at the National Gallery in London of 85 works by Edvard Munch (1863-1944) presents a unique chance to reassess this famous Norwegian's influence and talent. Perhaps ten of Munch's works will be relatively familiar to quite a wide audience here, largely from reproductions. But it is the less familiar ones which refresh the eye and make it easier to see Munch in a more precise context. I can think of few exhibitions which exude such emotional rawness: Munch deals with themes of love, Jealousy, anxiety, illness and death with moving directness and a general avoidance of sentimentality. 'Starry Night', 1895-7, one of the first paintings on view, is of a deep blue sky, with opposed shorelines in silhouette. For me, the single reflection across the water is strangely evocative of both the mood and nocturnal fixation of Jay Gatsby, Scott Fitzgerald's eponymous hero, another lovelorn and obsessive romantic.

Munch was not the only member of his family to walk the cliff-edges of the mind; his younger sister Laura was diagnosed as schizophrenic, while the artist himself was treated for eight months for a complete mental breakdown when in his forties. It is widely believed among more southerly folk that a disproportionate number of Munch's fellow countrymen were and are a few oars short of a longship — the influence of the Winter darkness, relative isolation and the more repressive aspects of Protestantism shouldering the blame for this supposed condition. Today lack of light in winter is recognised medically as a frequent factor in depressive illnesses.

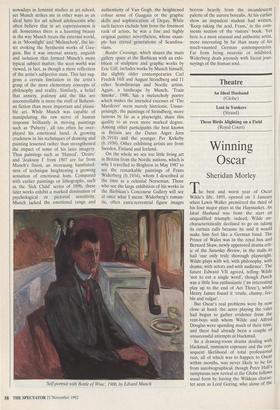

Munch's Frieze of Life is a series of inter- connected works which mingle memory and symbolism. His portrayal of wom- ankind variously as sphinx or vampire may not appeal overmuch to those engaged nowadays in feminist studies at art school, yet Munch strikes me in other ways as an ideal hero for art school adolescents who often believe that in art expressiveness is all. Sometimes there is a haunting beauty in the way Munch treats the external world, as in 'Moonlight' and 'Melancholy', the lat- ter evoking the Synthesist works of Gau- guin. But it was internal anxiety, anguish and isolation that formed Munch's more typical subject matter; the seen world was viewed, in fact, as though a mere reflection of the artist's subjective state. This last sug- gests a certain limitation in the artist's grasp of the more elementary concepts of philosophy and reality. Similarly, a belief that anxiety, jealousy and the like are uncontrollable is more the stuff of Bohemi- an fiction than more important and plausi- ble art. While Munch was capable of manipulating the raw nerve of human response brilliantly in moving paintings such as 'Puberty', all too often he over- played his emotional hand. A growing crudeness in his techniques of drawing and painting lessened rather than strengthened the impact of some of his later imagery. Thus paintings such as 'Hatred', 'Desire' and 'Jealousy I' from 1907 are far from Munch's finest, an increasing hamfisted- ness of technique heightening a growing sensation of emotional ham. Compared with earlier paintings or lithographs, such as the 'Sick Child' series of 1896, these later works exhibit a marked diminution of psychological or pictorial sensitivity. Munch lacked the emotional range and authenticity of Van Gogh, the heightened colour sense of Gauguin or the graphic skills and sophistication of Degas. While such factors exclude him from the foremost rank of artists, he was a fine and highly original painter nevertheless, whose exam- ple has stirred generations of Scandina- vians.

Border Crossings, which shares the main gallery space at the Barbican with an exhi- bition of sculpture and graphic works by Eric Gill, includes works by Munch himself, the slightly older contemporaries Carl Fredrik Hill and August Strindberg and 11 other Scandinavian and Nordic artists. Again, a landscape by Munch, 'Train Smoke', 1900, has a melancholy poetry which makes the intended excesses of 'The Murderer' seem merely histrionic. Unsur- prisingly, the paintings of Strindberg, more famous by far as a playwright, share this quality to an even more marked degree. Among other participants the best known in Britain are the Danes Asger Jorn (b. 1914) and the younger Per Kirkeby (b. 1938). Other exhibiting artists are from Sweden, Finland and Iceland.

On the whole we see too little living art in Britain from the Nordic nations, which is why I travelled to Brighton in May 1987 to see the remarkable paintings of Frans Widerberg (b. 1934), whom I described at the time as a celestial Norseman. Those who see the large exhibition of his works in the Barbican's Concourse Gallery will see at once what I mean. Widerberg's roman- tic, often extra-terrestrial figure images `Self-portrait with Bottle of Wine; 1906, by Edvard Munch borrow heavily from the incandescent palette of the aurora borealis. At his earlier show an impudent student had written, `Keep taking the acid, Frans,' in the com- ments section of the visitors' book. Yet here is a most unusual and authentic artist, more interesting by far than many of his much-vaunted German contemporaries. Far from being neurotic or inhibited, Widerberg deals joyously with literal jour- neyings of the human soul.

Previous page

Previous page