CHESS

It's a knockout

Raymond Keene

The very first chess tournament ever held was conceived and organised by that great English chess character Howard Staunton. This marvellous competition took place at London in 1851 and attracted most of the greatest players of the day, including Adolf Anderssen (the eventual winner), Lowenthal, Bird, Wyvill, Elijah Williams, Horwitz and of course Staunton himself. The format used was the knockout system, but in subsequent years its popu- larity declined in chess circles, in favour of the all-play-all and the 'Swiss'. The Swiss system permits a large number of players to contest a meaningful event in just a very few rounds and is now used for most Fide junior championships, the Olympiad, the British Championship and the Lloyds Bank Masters.

Recently, however, interest has grown again in knockout tournaments. Michael Adams's two triumphs earlier this year (which collectively netted him around £70,000 in prize money) in Brussels and in Tilburg both came in knockouts. The advantage of the knockout system is that draws become irrelevant, hence the sport- ing spectacle is intensified. Furthermore, ties are broken by rapid playoffs, which cannot be rated by the World Chess Federation. It is remarkable to note how many recent top events have not con- formed to the Fide rating criteria. They include the Fischer — Spassky match, Brussels, Tilburg and now the Paris Im- mopar Knockout, which finished last Sun- day. Perhaps top players no longer want to have their games rated. That certainly seems to be the trend.

In Paris Adams and Short were swiftly eliminated, along with Karpov and Tim- man, who was axed by Judith Polgar. Kasparov sped to the final, en route dispatching Kramnik, Polugaevsky and Kamsky. In the final Kasparov beat Anand by three games to one. The overall prize fund was £100,000. One of the problems with quick chess knockouts is that the quality of play tends to suffer. On the evidence from Paris Fischer would have no trouble in a match against Anand.

Kasparov — Anand: Immopar Trophy, Final, Game 3.

Position after 14 Bcl

Here Anand unearthed the appalling howler 14 . . . f5 and was shocked by the reply 15 Nxd5! which annihilates Black's centre and wins mate- rial into the bargain. Black cannot of course play 15 . • . Qxd5 on account of 16 Bc4 winning Black's queen. After the turther forlorn moves 15 • • . Bh5 16 Nf4 Bxf3 17 Bc4+ Kh8 18 Qxf3 Ng5 19 Qh5 Qe8 20 Qe2 Bb4 21 Nd5 Ne6 22 Nxb4 Nxb4 23 d5 Nc5 24 a3 Nba6 25 b4 Ne4 26 Bbl Nb8 27 e6 Black went on to lose on time on move 37.

Anand — Kasparov: Immopar Trophy, Final, Game 4; Sicilian Defence.

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 f4 Qc7 In game 2 of the final Kasparov tried 6 . . . e6 7 Qf3 Qb6 but lost. This is his attempt at an improvement. 7 a4 g6 8 Bd3 Bg7 9 Nf3 Nc6 10 0-0 Bg4 11 Qel 0-0 12 Qh4 Bxf3 13 Rxt3 e6 This move, combined with Black's queen retreat on move 14, is an original and fascinating idea. It is based on the perception that if Black achieves the thrust . . . d5 he will have an excellent position. 14 Be3 Qd8 15 Rafl d5 16 f5 If White does not try this his attack is still-born, but this appears, nevertheless, to be unsound. 16 . . • dxe4 17 Rh3 exf5 18 Bxe4 Hoping for 18 . . fxe4 19 Rxf6, but Kasparov is not fooled by this obvious trick, 18 . . . Re8 19 BxfS gxf5 20 RIO White's attack reaches its climax but Kasparov is ready with a devastating counter. 20 . . . Rxe3 21 Rxe3 Qb6 22 Qf2 Any other move would allow . . . Re8 intensifying the pin. The text sets a diabolical trap, but Kasparov is only too ready

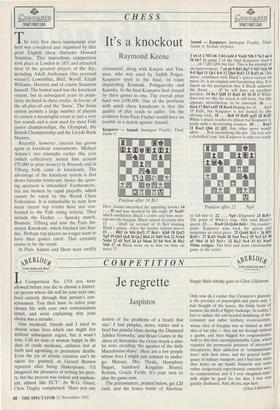

Position after 22 . . . Ng4

to fall into it. 22 . . . Ng4 (Dia'ram) 23 Re8+ The point of White's trap. This wins Black's queen. 23 . . . Rxe8 24 Qxb6 Bd4+ The counter- point. Kasparov wins back the queen and maintains an extra piece. 25 Qxd4 Rel + 26 Rfl Rxfl+ 27 Kxfl Nxd4 28 Ne4 Nxc2 29 Nc5 b5 30 a5 Nb4 31 h3 Ne3+ 32 Keg Nc4 33 b3 NxaS White resigns. The best and most entertaining game in the series.

Previous page

Previous page