Exhibitions 2

Bridget Riley: Works 1961-1998 (Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, Cumbria, till 31 January)

A world outside

John Spurling

Why Kendal? you might ask. The best answer is to go to see for yourself. The 18th-century Abbot Hall, set beside the swollen River Kent with a ruined Norman castle on a green hillock beyond, is as good a place as any in which to spend time with paintings as mysteriously beautiful as Brid- get Riley's. In fact, her work has always looked just as much at home on the walls of her parents' Georgian rectory in Corn- wall or her own terraced house in west London as in large metropolitan galleries.

These paintings need space and light and are given it in the bright white rooms of Abbot Hall's upper floor — but they bring everything else with them, both the stored essence of the natural world beyond the windows and the exhilaration of the artist's masterly devices for trapping it. `You have always maintained,' says Isobel Carlisle in an interview in the Abbot Hall catalogue, 'that your paintings do in art what nature does all around us.' People,' replies Riley, 'frequently experience visual events in nature which are far more violent, and even blinding, than anything I have ever done on canvas ... People would be very shocked indeed if the world itself was as dead in its appearance as they seem to expect a painting to be.' Turner would surely have agreed.

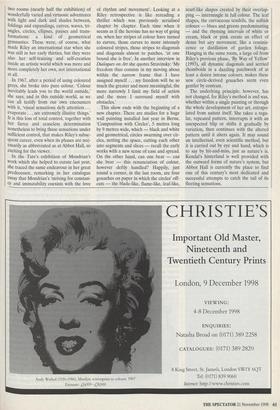

Starting with three figurative drawings from her student days and the Seurat-like `Blue Landscape' of 1959-60, this retro- spective, because it is relatively small, emphasises the coherence and continuity of her development. Coloured divisionism, Seurat's 'optical mixture', as Riley calls it in an interview in Dialogues on Art (Zwem- mer, 1995), the gathering of colours into forms and the dispersing of them into open areas, paradoxically showed her the way into the initially violent contrasts of her black and white abstractions. These paint- ings about 'states of composure and distur- bance' are represented at Abbot Hall by Bridget Riley's 'July 13th Revision of July 1 1 th Bassacs. 98', gouache on paper two rooms (nearly half the exhibition) of wonderfully varied and virtuosic adventures with light and dark and shades between, foldings and expandings, curves, waves, tri- angles, circles, ellipses, pauses and trans- formations: a kind of geometrical gymnastics. These were, of course, what made Riley an international star when she was still in her early thirties, but they were also her self-training and self-creation Inside an artistic world which was more and more completely her own, not international at all.

In 1967, after a period of using coloured greys, she broke into pure colour. 'Colour Inevitably leads you to the world outside,' she says, and in this outside world, as we can all testify from our own encounters with it, 'visual sensations defy attention ... evaporate ... are extremely illusive things.' It is this loss of total control, together with her fierce and ceaseless determination nonetheless to bring these sensations under sufficient control, that makes Riley's subse- quent career, even when its phases are nec- essarily as abbreviated as at Abbot Hall, so exciting for the viewer.

In the Tate's exhibition of Mondrian's work which she helped to curate last year, she traced the same endeavour in her great predecessor, remarking in her catalogue essay that Mondrian's 'striving for constan- cy and immutability coexists with the love of rhythm and movement'. Looking at a Riley retrospective is like rereading a thriller which was previously serialised chapter by chapter. Each time when it seems as if the heroine has no way of going on, when her stripes of colour have turned to curves, those curves to more intensely coloured stripes, those stripes to diagonals and diagonals almost to patches, 'at one bound she is free'. In another interview in Dialogues on Art she quotes Stravinsky: 'My freedom thus consists in my moving about within the narrow frame that I have assigned myself ... my freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful, the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles.'

This show ends with the beginning of a new chapter. There are studies for a huge wall painting installed last year in Berne, `Composition with Circles', 5 metres long by 9 metres wide, which — black and white and geometrical, circles swarming over cir- cles, netting the space, cutting each other into segments and slices — recall the early works with a new sense of ease and spread. On the other hand, can one bear — can she bear — this renunciation of colour, however deftly handled? Happily, just round a corner, in the last room, are four gouaches on paper in which the circles' off- cuts — the blade-like, flame-like, leaf-like, scarf-like shapes created by their overlap- ping — intermingle in full colour. The leaf shapes, the curvaceous tendrils, the softish colours — blues and greens predominating — and the rhyming intervals of white or cream, black or pink create an effect of dense but airy movement, like a reminis- cence or distillation of garden foliage. Hanging in the same room, a large oil from Riley's previous phase, `By Way of Yellow' (1993), all dynamic diagonals and serried rhomboids in a dazzling patchwork of at least a dozen intense colours, makes these new circle-derived gouaches seem even gentler by contrast.

The underlying principle, however, has not changed, for,Riley's method is and was, whether within a single painting or through the whole development of her art, extrapo- lated from nature itself. She takes a regu- lar, repeated pattern, interrupts it with an unexpected blip or shifts it gradually by variation, then continues with the altered pattern until it alters again. It may sound an intellectual, even scientific method, but it is carried out by eye and hand, which is to say by hit-and-miss, just as nature's is. Kendal's hinterland is well provided with the outward forms of nature's system, but Abbot Hall is currently the place to find one of this century's most dedicated and successful attempts to catch the tail of its fleeting sensations.

Previous page

Previous page