A FOUNDLING FATHER TO OUR CHILDREN

This week is the 250th anniversary of Britain's oldest

chartered children's charity. Alexandra Artley

sees in its history the social problems of today

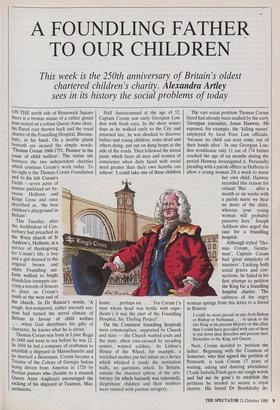

ON THE north side of Brunswick Square there is a bronze statue of a rather genial Man seated on a robust Queen Anne chair, his flared coat thrown back and the royal charter of the Foundling Hospital, Blooms- bury, in his hand. On a marble plinth beneath are incised the simple words: ' Thomas Coram 1668-1751. Pioneer in the cause of child welfare'. The statue sits between the two independent charities which continue Coram's work today. To his right is the Thomas Coram Foundation and to his left Coram's Fields – seven acres of mature parkland set be- tween Holborn and Kings Cross and once described as, 'the best children's playground in Britain'.

• • when God distributes his gifts of character, he knows what he is about.'

Thomas Coram was born in Lyme Regis in 1668 and went to sea before he was 12. In 1694 he led a company of craftsmen to establish a shipyard in Massachusetts and he married a Bostonian. Coram became a Trustee of the Colony of Georgia before being driven from America in 1720 by Puritan pastors who (hostile to a staunch Queen Anne Anglican) encouraged the sacking of his shipyard at Taunton, Mas- sachusetts. Half Americanised at the age of 52, Captain Coram saw early Georgian Lon- don with fresh eyes. In the short winter days as he walked early to the City and returned late, he was shocked to discover babies and young children, some dead and others dying, put out on dung heaps at the side of the roads. Then followed the moral panic which faces all men and women of conscience when daily faced with social need greater than their own hearths can relieve: 'I could take one of these children home . . . perhaps six. . . .' For Coram man whose head was fertile with expe- dients') it was the start of the Foundling Hospital, his 'Darling Project'.

On the Continent foundling hospitals were commonplace, supported by Church and state — the Church wanted souls and the state, often criss-crossed by invading armies, wanted soldiers. At Lisbon's House of the Wheel, for example, a wretched mother put her infant on a device which whisked it inside the institution walls, no questions asked. In Britain, outside the charmed sphere of the aris- tocracy (in which bastardy was tolerated), illegitimate children and their mothers were treated with puritan savagery. Although styled 'Tho- mas Coram, Gentle- man', Captain Coram had 'great simplicity of manners'. Lacking both social graces and con- nections, he failed in his first attempt to petition the King for a foundling hospital charter. The saltiness of the angry seaman springs from this letter to a friend in Boston:

I could no more prevail on any Arch Bishop or Bishop or Nobleman . . . to speak to the late King or his present Majesty on this affair than I could have prevailed with any of them to put down their Breeches and present their Backsides to the King and Queen.

Next, Coram decided to 'petition the ladies'. Beginning with the Countess of Somerset, who first signed the petition at Petworth, it took Coram 17 years of waiting, asking and dancing attendance (`Lady Isabella-Finch gave me rough words and bid me be gone') to establish the petitions he needed to secure a royal charter. His friend Dr Brocklesby de-

scribes Thomas Coram's 'ardour and anxi- ety' as if every deserted child had been his own; 'even people of rank began to be ashamed to see a man's hair become grey in the course of a solicitation by which he could get nothing'. The charter was at last granted in 1739 when Coram was 71. To decorate the massive red wax seal which dangles from the rolled-up charter in Hogarth's portrait of Captain Coram, he chose MoseS in the bullrushes, 'the first foundling we hear of'.

The site for the Foundling Hospital was bought from the Earl of Salisbury in 1740 — four fields in an outlying area called Bloomsbury. Theodore Jacobson, a City merchant turned architect, was chosen to design it and his scheme was a simple classical building arranged on three sides of a square (a wing for boys and a wing for girls separated by a chapel). While building began, the Foundling first opened its doors in March 1741 in a house temporarily rented in Hatton Garden. The first two children were baptised as Thomas and Eunice Coram and Captain Coram stood as godfather to 20 more. Although the Foundling Hospital was demolished in 1926 (the conservation cause célèbre of its day) the unique dignity and warmth of this great institution can be still sensed at its newer premises, the Thomas Coram Foundation in Brunswick Square.

On Tuesday, after the service in St Andrew's, Holborn, the Governors of the Thomas Coram Foundation invited 400 people to a party in the Court Room. Beneath an exuberant plasterwork ceiling by William Wilton, the rich apricot- coloured walls glowed with paintings by Hogarth, Francis Hayman, Gainsborough and James Wills. Apart from the Found- ling Hospital, Captain Coram was also the father of the Royal Academy. By en- couraging his friend Hogarth to show his works at the Foundling to attract donations from the fashionable public, Coram spurred Hogarth's friends (in a painter's colony in St Martin's Lane) to found the Royal Academy.

The bar was set up under Hogarth's red-coated portrait of Coram. To its right was Roubilliac's bust of Handel (another benefactor) and a scroll bearing words from the 27th Psalm, 'When my father and my mother forsake me, the Lord taketh me up.' Chattering happily beneath the art, the guests were former Foundling children grown to adulthood, present-day foster and adoptive parents (whom the Governors seek out for particu- larly 'hard-to-place' children), teachers past and present, clergy, fund-raisers, and the mayors of Camden, Islington and Lyme Regis. 'We won this in a raffle,' said the present Director, Colin Masters, pointing to Hogarth's 'March of the Guards to Finchley'. (Hogarth had indeed raffled it to raise money for Coram, and his wife, Jane was one of Coram's early foster-mothers.) The windows of the Court Room look

out over a haze of trees in Coram's Fields. Beneath them on quieter days stand three or four dignified wooden cases lined with dark blue velvet and filled with the pathetic tags and tokens attached by sorrowing mothers to the babies they were about to leave.

What would you choose to leave with a child you will never see again? Tokens left between 1741 and 1760 include a frayed pink silk purse with `ND' embroidered in black beads; a mother-of-pearl heart with the letters 'EL'; fragments of coral neck- laces; some glass buttons; an ivory fish with a gentle eye drawn on it; a flat piece of shell scratched with the words, 'James, son of James Concannon, Late or Now of Jamaica'; a silver thimble perhaps deliber- ately crushed; a small dark red heart made of a heavy ribbed silk called lute-string; a piece of cloth hastily ripped from a dress or jacket; a scrap of paper edged with brown silk bearing the words, 'in remembrance of E.B. November 2nd 1756' and a yellowing lawn baby's cap edged with lace. On a small bronze disc is inscribed, 'Nov. 10th, half an hour after 12 o'clock' — perhaps the exact time of a birth engraved for ever on the mother's heart. The conflicting emo- tions of relief and pain which swept over applicants to the Foundling Hospital were recorded by an eye-witness at its gates:

The Expressions of Grief of the Women whose Children could not be admitted were Scarcely more observable than those of some of the women who had parted with their children, so that a more moving Scene can't well be imagined.

Among the nine tons of documents which the Foundling has accumulated in the course of dealing with 27,000 children are notes by mothers who could write or whose friends could write for them.

No 6575: It is Earnestly intreated that the Child may be taken Care of as the Disconso- late parents Hope soon to be in a situation to own it . . . . Cruel Separation. Wednesday December 7th, 1757.

No. 12719: Joseph. Born in London April 28, 1759. Va! mon Enfant prend la Fortune.

No. 734: 'Who Breathes must suffer. And who thinks must Mourn. And He Alone is Blest Who ne'er was born.'

The details of one baby were taken down very briefly by the recording clerk: 'A paper on the breast — Clout [cloth] on the head.'

Besides these manuscripts lies another with which we are instantly familiar — the Foundling Hospital version of Messiah copied by Handers amanuensis, John Christopher Smith. Handel was another great artist-benefactor of the Foundling and his fashionable concerts given in the hospital chapel raised £7,000 (a stupendous sum in those days).

From March 1741 when the Foundling Hospital first opened its doors to March 1756 when, for four years, Parliament made a grant towards the admission of children on demand, 1,384 children were received (a figure much lower than similar institutions in Europe). 'Alas,' wrote Jonas Hanway, 'what were 1,384 infants to the thousands that were still drooping and dying at the hands of parish nurses?' The Governors, who through limited resources had been forced to restrict admission by a ballot using red, black and white balls, were themselves appalled at the enormous numbers of children they had to turn away. Aged 74, Thomas Coram began to petition (in vain) for a second Foundling Hospital in Westminster. At this stage in his life Captain Coram had impoverished himself and it was a subscription raised by the kindly Jewish financier Sampson Gideon that kept him in his last years. It is recorded that at this time he liked to sit in the Foundling Hospital's colonnades distri- buting gingerbread and watching the chil- dren with tears in his eyes. He died on 29 March 1751 in lodgings in Spur Street (now Panton Street) near Leicester Square and had asked to be buried under the Found- ling chapel then nearing completion. As his body was carried through the gates in Guilford Street, his plain elm coffin dis- appointed the crowd.

In the 18th-century, the Governors of the Foundling Hospital pioneered the best social case-work of today. Young appren- tices, for example, were often at risk from brutal treatment, and the Governors usual- ly attempted to prosecute on their behalf. Some cases were utterly barbarous. Wil- liam Butterworth, a weaver of Manchester, regularly kicked his apprentice Jemima Dixon so hard in the stomach that she became incontinent; he forced her to eat her own excrement. Job Wyatt, a wood-screw maker of Tatehill, raped his 11-year-old apprentice Sarah Drew and beat her if she refused him. Mary Jones, apprenticed to Mrs Brownrigg of Fetter Lane, escaped back to the Foundling with an eye so badly injured it was feared she would lose it (Mrs

Brownrigg, a notorious sadist, was later hanged at Tyburn for the torture and murder of innumerable parish apprentices who had no one to turn to). To many people in the outside world Coram's chil- dren were foundlings — illegitimate and therefore almost subhuman. In legally pursuing bad masters, medically attending to the children and offering them support and counselling in later life, the Governors of the Foundling Hospital set a precedent for protecting young people 'leaving care'. The Thomas Coram Foundation now runs sheltered accommodation for young people leaving care and settling into the adult world of work.

Long-established charities have an almost Darwinian response to 'adapt or die'. On a bright autumn morning I arrived at the Coram Homeless Children's Project to see just one example of the way an old foundation has adapted its work to meet contemporary needs. One of the many tragedies of 'hotel homelessness' is that Children cooped up in squalid hotel rooms lack not only space (even to learn to walk) but play materials appropriate to their age. In child development 'play', said the great child psychologist, Jean Piaget, 'is the child's work.'

The Coram Homeless Children's Project is run by Lonica Vanclay, who first showed me the Coram toy store. In a small classical building (which housed a swimming pool in the latter days of the Foundling Hospital) were racks of very clean playthings, rang- ing from soft furry toys for babies to first books, crayons, paints and mechanical `play-centres'. Chess and draughts were available for older children. Heaped ab- out, because a toy firm in Yorkshire happened to donate £800 worth of them, were several dozen big red and yellow plastic mechanical diggers for toddlers to drive. Lonica Vanclay explained that on Mondays one Coram team made a month- ly 'toy library' trip to bed-and-breakfast hotels in West Hampstead. First the names, ages and addresses of children were checked on a card index file. Then play- things were loaded into orange and blue plastic crates.

In front of Gregory House, beneath mature rustling trees, Dominic Fox and Hasina Khan loaded the crates into a royal-blue mini-bus which had the words, `Thomas Coram; Caring for children since 1739' scripted in a copper-plate style on the side. Driving purposefully out of Mecklen- burgh Square, Dominic explained that the West Hampstead area alone encompassed 50 homeless families (placed there by Camden and Westminster) who have approximately 100-150 children between them.

Half an hour later we reached a shabby north London neighbourhood. The first hotel call was on Room 3, occupied by an Irish nurse, her unem- ployed husband and their 16-month-old son. Hotel homelessness is a timeless zone. At 11.15 in the morning, the curtains were drawn, the television glowed quietly on top of a fridge next to the double bed and the mother greeted us warily in a dressing- gown. The purpose of these 'toy visits' is also to lend adults a sympathetic ear. While the nurse talked about her idea of `going back on night duty' if her husband could look after the boy, the child stum- bled forward to the plastic crate for toys.

`What would you like, little one?' said Hasina Khan, as he finally settled on a pack of three bright fabric 'bricks', one with a bell inside.

Fifteen minutes later, in the same hotel, Dominic Fox negotiated his crate of toys through a rabbit warren of heavy fire doors, dog-leg bends in the stairs and converted landings to reach Room 8, occu- pied by a Bengali couple with four chil- dren. Three of the children were at school. As there were no chairs (and no table) in the room, the father lay on a bed covered with a brown candlewick bedspread. Above him was suspended a plastic carrier- bag containing several bars of Cadbury's fudge.

Hasina Khan interpreted lightly and comfortably in Sylheti (now the second language in inner London). Soon the worn Bengali mother brought a child from a second room. Shelim turned out to be a mentally handicapped boy of 12 who is partially deaf and whose left ear was bound up from a recent operation. Dominic Fox offered him things from the toy crate. There was a packet of crayons, a small painting set, a good wad of scrap paper to draw on, a bottle of non-toxic children's glue and a Puffin large-format copy of Raymond Brigg's famous children's story, The Snowman. Shelim was delighted by the bottle of children's glue.

`For me?' he asked.

`Yes. For you.'

His father explained, via Hasina, that he could not offer us a seat or, indeed,

anything else. Instead, he insisted thaf I take a cigarette. Later, as we stiangersleft the room, Shelim, still seated on his parents' bed, clumsily seized The Snow- man with joy.

On the plight of thousands of British children growing up in bleak hotel rooms, the Governois of the Thomas Coram Foundation recently remarked that it `should be as horrific to sensitive people as the children cast aside on dung heaps were to Thomas Coram 250 years ago'. To try to help the growing number of needy children and young people in London the Founda- tion is, in the words of its director, Colin Masters, 'seriously fund-raising for the first time in a hundred years'. Thinking of the artists and musicians who had provided the `Live Aid' of the 18th century, he added, `And this time we have not got Handel.'

Donations would be separately welcomed by: The Thomas Coram Foundation, 40 Brunswick Square, London WCIN lAZ and by: Coram's Fields, 93 Guilford Street, London WC1N 1DN.

Previous page

Previous page