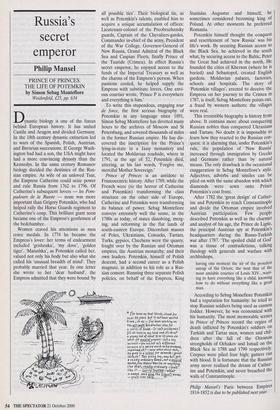

Russia's secret emperor

Philip Mansel

PRINCE OF PRINCES: THE LIFE OF POTEMKIN by Simon Sebag Montefiore Weidenfeld, £25, pp. 634 Dynastic biology is one of the forces behind European history. It has united Castile and Aragon and divided Germany. In the 18th century dynastic extinction led to wars of the Spanish, Polish, Austrian, and Bavarian successions. If George Wash- ington had had a son, the USA might have had a more convincing dynasty than the Kennedys. In the same century Romanov biology decided the destinies of the Rus- sian empire. As wife of an unloved Tsar, the Empress Catherine could seize power and rule Russia from 1762 to 1796. Of Catherine's subsequent lovers — les Pom- padours de la Russie — none was more important than Grigory Potemkin, who had helped rally the Horse Guards regiment to Catherine's coup. This brilliant giant soon became one of the Empress's gentlemen of the bedchamber.

Women craved his attentions as men crave medals. In 1774 he became the Empress's lover: her terms of endearment included `grishenka', 'my dove', 'golden tiger'. `MatushIca', as Potemkin called her, valued not only his body but also what she called his 'unusual breadth of mind'. They probably married that year. In one letter she wrote to her 'dear husband', the Empress admitted that they were bound 'by all possible ties'. Their biological tie, as well as Potemkin's talents, enabled him to acquire a unique accumulation of offices: Lieutenant-colonel of the Preobrazhensky guards, Captain of the Chevaliers-gardes, Commander in-chief of the army, President of the War College, Governor-General of New Russia, Grand Admiral of the Black Sea and Caspian Fleets, finally Prince of the Tauride (Crimea). In effect Russia's secret emperor, he enjoyed access to the funds of the Imperial Treasury as well as the charms of the Empress's person. When passions cooled, he helped supply the Empress with substitute lovers. One envi- ous courtier wrote, 'Prince P is everywhere and everything is him.'

To write this stupendous, engaging tour de force, the first serious biography of Potemkin in any language since 1891, Simon Sebag Montefiore has devoted many hours to the archives of Moscow and St Petersburg, and covered thousands of miles in the former Russian empire. He has dis- covered the inscription for the Prince's lying-in-state in a Jassy monastery and located the Moldavian roadside, where in 1791, at the age of 52, Potemkin died, uttering, as his last words, 'Forgive me, merciful Mother Sovereign.'

Prince of Princes is an antidote to Francocentric history. After 1789, while the French were (to the horror of Catherine and Potemkin) transforming the class structure on the other side of Europe, Catherine and Potemkin were transforming its balance of power. Sebag Montefiore conveys extremely well the sense, in the 1780s as today, of states dissolving, merg- ing, and reforming in the flat lands of south-eastern Europe. Discordant masses of Poles, Ukrainians, Cossacks, Tartars, Turks, gypsies, Chechens were the quarry, fought over by the Russian and Ottoman empires, the Austrian monarchy, and their own leaders. Potemkin, himself of Polish descent, had a second career as a Polish magnate, in addition to his role as a Rus- sian consort. Running three separate Polish policies, on behalf of the Empress, King Stanislas Augustus and himself, he sometimes considered becoming king of Poland. At other moments he preferred Romania.

Potemkin himself thought the conquest and resettlement of 'new Russia' was his life's work. By securing Russian access to the Black Sea, he achieved in the south what, by securing access to the Baltic, Peter the Great had achieved in the north. He founded the cities of Kherson (where he is buried) and Sebastopol, created English gardens, Moldavian palaces, factories, schools and hospitals. The story of `Potemkin villages', erected to deceive the Empress on her journey to the Crimea in 1787, is itself, Sebag Montefiore points out, a fraud by western authors; the villages were real.

This irresistible biography is history from above. It contains more about conquering Russian nobles than conquered Ukranians and Tartars. No doubt it is impossible to learn how they reacted to the Russian con- quest: it is alarming that, under Potemkin's rule, the population of 'New Russia' increased through immigration by Greeks and Germans rather than by natural means. The only drawback is the occasional exaggeration in Sebag Montefiore's style. Adjectives, adverbs and similes can he piled on with the same abandon with which diamonds were sewn onto Prince Potemkin's coat front.

After 1782 the 'great design' of Cather- ine and Potemkin to reach Constantinople and divide the Ottoman empire involved Austrian participation. Few people described Potemkin as well as the charmer and analyst of his age, the Prince de Ligne, the principal Austrian spy at Potemkin's headquarters during the Russo-Turkish war after 1787. 'The spoiled child of God' was a tissue of contradictions, talking theology with generals and warfare with archbishops, having one moment the air of the proudest satrap of the Orient, the next that of the most amiable courtier of Louis XIV...want- ing to have everything like a child, knowing how to do without everything like a great man.

According to Sebag Monefiore Potemkin had a reputation for humanity: he tried to stop Russian soldiers being used as cannon fodder. However, he was economical with his humanity. The most memorable scenes in Prince of Princes record the orgies of death inflicted by Potemkin's soldiers on Turkish and Tartar men, women and chil- dren after the fall of the Ottoman strongholds of Ochakov and Ismail on the Black Sea in 1788 and 1790 respectively. Corpses were piled four high; gutters ran with blood. It is fortunate that the Russian army never realised the dream of Cather- ine and Potemkin, and never breached the walls of Constantinople.

Philip Mansel's Paris between Empires 1814-1852 is due to be published next year.

Previous page

Previous page