Exhibitions 2

Drink and Be Merry: Wine and Beer in Ancient Times (The Jewish Museum, New York, till 5 Nov)

Lifting the spirit

Roger Kimball

Mosaic depicting camel carrying wine amphora, Kissufim, Israel, 6th century AD Many students of Thomas Aquinas have been puzzled by the fact that he pro- vides only five, not six, arguments for the existence of God. There's the cosmological, the teleological, the ontological, etc. — but what about the oenological? How could the Angelic Doctor have neglected this impor- tant arrow in his quiver of sed contras? There is wine, therefore God exists. Quod erat bibendum, what?

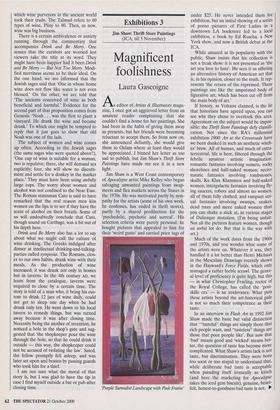

Although the atgumentum vino has been sadly neglected by theologians, the divine nature of the quaff that really cheers has been recognized by all competent authori- ties. Plato ascribed the invention of wine to the gods, as did the people in what is now Iran who first cultivated the vine in the 6th century BC. This exhibition provides a kind of archaeological and historical tour of the paraphernalia associated with making, transporting, and consuming wine and beer in the ancient Near East, exploring, as the exhibition catalogue says, 'two of the oldest known beverages, valued throughout time for their abilities to lift spirits, inspire reli- gious fervor, deaden pain and cure illness'.

The excellent catalogue is an essential adjunct to this exhibition, which is spon- sored, appropriately, by Joseph E. Seagram and Sons, Inc. The catalogue manages to be both scholarly and entertaining and pro- vides the animating information that makes the many krateroi, amphorae, kylikes, kan- tharoi and rhyta (pitchers and jugs and cups to us) that — together with various mosaics, wall paintings, and measuring devices — populate Drink and Be Merry.

The exhibition also includes a rudimen- tary recreation of an ancient wine shop. It is not exactly Berry Bros & Rudd, but it does suggest the laudable seriousness with which wine purveyors in the ancient world took their trade. The Talmud refers to 60 types of wine, Pliny to 80. Then, as now, wine was big business.

There is a certain ambivalence or anxiety running through the commentary that accompanies Drink and Be Meny. One senses that the curators are worried lest viewers take the title at its word. They might have been happier had it been Drink and Be Meny — But Not Too Meny. Modi- fied merriness seems to be their ideal. On the one hand, we are informed that the Jewish sages said that 'One in whose home wine does not flow like water is not even blessed.' On the other, we are told that `The ancients conceived of wine as both beneficial and harmful.' Evidence for the second part of that proposition comes from Genesis: 'Noah . . was the first to plant a vineyard. He drank the wine and became drunk.' To which one might be tempted to reply that it just goes to show that old Noah was one of the lads.

The subject of women and wine comes up often. According to the Jewish sages (the same sages who were quoted above?), `One cup of wine is suitable for a woman; two is repulsive; three, she will demand sex explicitly; four, she will show no discern- ment and settle for a donkey in the market place.' They must have been using awfully large cups. The worry about women and alcohol was not confined to the Near East. The Roman statesman Cato is said to have remarked that the real reason men kiss women on the lips is to see if they have the scent of alcohol on their breath. Some of us will undoubtedly conclude that Cato, though sound on Carthage, was a bit out of his depth here.

Drink and Be Meny also has a lot to say about what we might call the culture of wine drinking. The Greeks indulged after dinner at intellectual drinking-and-talking- parties called symposia. The Romans, clos- er to our own habits, drank wine with their meals. As the production of wine increased, it was drunk not only in homes but in taverns. In the 4th century AD, we learn from the catalogue, taverns were required to close by a certain time. The story is told of a man who, it being his cus- tom to drink 12 jars of wine daily, could not get to sleep one day when he had drunk only ten. He went down to his local tavern to remedy things, but was turned away because it was after closing time. Necessity being the mother of invention, he noticed a hole in the shop's gate and sug- gested that 'the shopkeeper pour the wine through the hole, so that he could drink it outside — this way, the shopkeeper could not be accused of violating the law'. Sated, the fellow promptly fell asleep, and was later set upon and beaten by passing guards who took him for a thief.

I am not sure what the moral of that story is, but I was glad to have the tip in case I find myself outside a bar or pub after closing time.

Previous page

Previous page