ADOLF, WE HARDLY KNEW YOU

On the 100th anniversary of what makes a fascist

A SCHILLING life will give you as much as you need of the facts: how he was born on 20 April in Braunau, Austria, 100 years ago, how Father ignored him, how he ran away to Vienna, painted houses, cathed- While not exactly the man on the Klagenfurt omnibus, Adolf was not Your omnicompetent Renaissance figure, A loony? The archetypical bad-hat Austrian? Despite the 100,000 books Which have already appeared on his regime the personality of the Fiihrer himself re- mains elusive, his legacy shapeless. The Word 'Nazi' sounds satisfyingly close to Nasty', and along with 'fascist', which hisses so well, has become a useful term of abuse, particularly favoured by the various claimants to the seamed robe of Karl Marx. People as diverse as Charles de Gaulle, Pol Pot and Richard M. Nixon have all in their time been labelled fascists by experienced and presumably know- ledgeable name-callers, who seem to have had in mind some secret mixture of nationalism, authoritarianism, opportun- ism, demagoguery, duplicity and general unlikableness.

None of these attributes is rare among politicians, so that his name tends to become a labour-saving device, a substi- tute for thought. 'Pitiless', 'brutal' and 'fanatical' were among Adolf s own favourite descriptions of himself, and his career can readily be misused to persuade subsequent generations of the need for constant unreflecting struggle against the bad guys who seem to have recurred so regularly since in human conflicts, always on the other side. The child's game of `spot-the-Hitler' will be, we may be sure, played for a long time to come.

Well, it certainly causes more shudders than calling people Caesar, Bonaparte or Cromwell, and it could not have happened to a lovelier person. The idea of a hyperac- tive bad hat who brings the world close to ruin is one that would, come to think of it, have appealed mightily to Adolf himself.

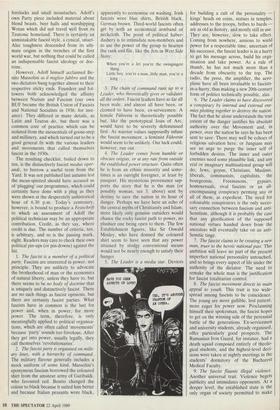

On the other hand, he was the most imitated politician on earth in the late 1930s, not because he was evil but because he was so wildly, asto- nishingly successful. No one loves or even fears a loser, so today's politi- cians are not likely to acknowledge his inspira- tion. We therefore risk either failing to see that Adolf invented a highly viable form of politics, unstable, like capitalism (with which it has no other connection, in- cidentally), but still cap- able of causing a great deal of mischief, or of having no term with which to isolate and dis- cuss this protean phe- nomenon. We need to rescue fascism from the fascists and anti-fascists, in short, in order to pin its exponents firmly to the analytic chart.

The director Chris Hale and I were actually engaged in doing that last summer in order to make a series of television programmes, based on the American newsreel documentary series The March of Time, for Channel Four, the general subject being the rise of fascism in the 1930s. In that decade fascists were ten a pfennig around the world and with scores of Fiihrers, would-be Fiihrers and pseudo- Fiihrers to consider some classification was called for, which in turn required a work- ing definition. Not all of them wore (or wear) trenchcoats and few had floppy forelocks and small moustaches. Adolf s own Party piece included material about blond beasts, beer halls and worshipping Wotan which did not travel well from its Teutonic homeland. There is certainly an unmistakable fascist style, a cynical, smart- Alec toughness descended from its ulti- mate origins in the trenches of the first world war, but nothing that could be called an indispensable fascist ideology or doc- trine.

However, Adolf himself acclaimed Be- nito Mussolini as il miglior fabbro and the two dictators hung together almost to their respective sticky ends. Founders and fol- lowers both acknowledged the affinity between Nazism and Fascism (our own BUF became the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936, for inst- ance). They differed in many details, as Latin and Teuton do, but there was a common core of practice which can be isolated from the inessentials of goose-step and millinery, and which turned out to be a good general fit with the various leaders and movements that called themselves fascist in the 1930s.

The resulting checklist, boiled down to ten, is the distinctively fascist modus oper- andi, to borrow a useful term from the Yard. It was not published last autumn lest the mean-spirited should have accused us of 'plugging' our programmes, which could certainly have done with a plug as they were shown at the desperately unhistorical hour of 6.30 p.m. Today's centenary, however, is bound to produce a Festschrift to which an assessment of Adolf the political technician may be an appropriate contribution. Credit, as they say, where credit is due. The number of criteria, ten, is arbitrary, and so is the passing mark, eight. Readers may care to check their own political pin-ups (or pin-downs) against the list.

1. The fascist is a member of a political party. Fascists are interested in power, not principle. They are unlikely to advocate the brotherhood of man or the economics of natural liberty, unless they have to, but there seems to be no body of doctrine that is uniquely and distinctively fascist. There are no such things as fascist opinions, but there are certainly fascist parties. What fascists have in common is the lust for power and, when in power, for more power. The term, therefore, is only meaningfully applied to political organisa- tions, which are often called 'movements' because 'party' sounds too frivolous. After they get into power, usually legally, they call themselves 'revolutionaries'.

2. The fascist party is organised on milit- ary lines, with a hierarchy of command. The military flavour generally includes a mock uniform of some kind. Mussolini's eponymous fascism borrowed the coloured shirt from the amateur army of Garibaldi, who favoured red. Benito changed the colour to black because it suited him better and because Italian peasants wore black,

apparently to economise on washing. Irish fascists wore blue shirts, British black, German brown. Third-world fascists often get by with an economical armband or neckcloth. The point of political haber- dashery is to intimidate non-members and to use the power of the group to hearten the rank and file, like the Jets in West Side Story:

When you're a Jet you're the swingingest thing.

Little boy, you're a man, little man, you're a king . . .

3. The chain of command runs up to a Leader, who theoretically gives or validates all the orders. Fascist leaders have so far all been male, and almost all have been, or claimed to have been, ex-servicemen. A female Fiihrerin is theoretically possible but, like the prototypical Joan of Arc, would have to be severely defeminised first. As warrior values supposedly infuse the fascist movement, a feminist Fiihrerin would seem to be unlikely. Our luck could, however, run out.

4. The Leader comes from humble or obscure origins, or at any rate from outside the established power structure. Quite often he is from an ethnic minority and some- times is an outright foreigner, at least by passport. His mysterious provenance sup- ports the story that he is the man (or possibly woman, see 3. above) sent by destiny to save the nation in its hour of danger. Perhaps we have here an echo of the central myths of Christianity and Islam; more likely only genuine outsiders would chance the rocky fascist path to power, no plushier one being open to them. The few Establishment figures, like Sir Oswald Mosley, who have donned the coloured shirt seem to have seen that any power attained by stodgy conventional means would not be nearly enough to satisfy their hunger.

5. The Leader is a media star. Devices for building a cult of the personality — kings' heads on coins, statues in temples, addresses to the troops, bribes to bards — are as old as history, and mostly still in use. They are, however, slow to take effect. Coming from nowhere, anxious to wield power for a respectable time, uncertain of his successor, the fascist leader is in a hurry to get his message across, build his orga- nisation and take power. As a rule of thumb, he has not much more than a decade from obscurity to the top. The radio, the press, the amplifier, the aero- plane have all been invaluable to fascists- in-a-hurry, thus making a new 20th-century form of politics technically possible, alas.

6. The Leader claims to have discovered a conspiracy by internal and external ene- mies plotting together to destroy the nation. The fact that he alone understands the true extent of the danger justifies his absolute authority over the Movement and, in power, over the nation he says he has been sent to save. There may well be echoes of religious salvation here, or Jungians may see an urge to purge the inner self of forbidden desires. The inner and outer enemies need some plausible link, and any real or imaginary multinational group will do; Jews, goyim, Christians, Muslims, liberals, communists, capitalists, the

bourgeoisie, Freemasons, gypsies, homosexuals, rival fascists or an all- encompassing conspiracy perming any or all of them, as expedient. The need for colourable conspirators is the only neces- sary connection between fascism and anti- Semitism, although it is probably the case that any glorification of the supposed national virtues handed down from the ancestors will eventually take on an anti- Semitic tinge.

7. The fascist claims to be creating a new man, truer to the heroic national past. This ambition will leave no part of the present imperfect national personality untouched, and so brings every aspect of life under the authority of the dictator. The need to remake the whole man is the justification for fascist totalitarian control.

8. The fascist movement directs its main appeal to youth. This trait is too wide- spread among fascists to be coincidence. The young are more gullible, less patient, more eager for power now. Proclaiming himself their spokesman, the fascist hopes to get on the winning side of the perennial battle of the generations. Ex-servicemen and university students, already organised, offer particularly good prospects. The Rumanian Iron Guard, for instance, had a death squad composed entirely of theolo- gical students, and the highest-level deci- sions were taken at nightly meetings in the students' dormitory of the Bucharest Medical Faculty.

9. The fascist flaunts illegal violence. Another universal trait. Violence begets publicity and intimidates opponents. At a deeper level, the established state is the only organ of society permitted to make

blood sacrifices by ordering executions and waging war. In shedding blood, therefore, the fascist is laying claim to the essential of state power without the formality of coup or. election, and brawl by brawl under- mines and supplants the legitimate govern-, ment. After power is attained, the fascist uses illicit force or threats of force against the international order, by the same logic. He avoids, however, conflict with the professional exponents of violence, the regular armed forces, because his ill- trained, out-of-shape street-fighting gangs are bound to lose. All fascist movements have in the end been put down by armies, either of their own countries or other people's. The real in the end defeats the fake.

10. The fascist seeks power by organising a coalition of dissidents against the estab- lished order. What they are complaining about is not important. They can be against high prices, low prices, puritanism and Pornography, all at the same time. The leader alone decides or deletes fascist Policy, and he is not obliged to he consis- tent, or even explain what he has in mind. It is this slippery, protean quality that has baffled intellectuals, bewildered opponents and made it impossible to define fascism either by its doctrine or its objectives, but only by its methods. Fascist flexibility is a. Is° the basis of what was long hoped to be Impossible, the co-operation of fascist states to intimidate their common oppo- nents of the moment. Which is why, Ultimately, fascism leads to war.

ut in decalogue form this essence of Adolf, or skeletal fascism, may seem rather thin and glamourless. Where are the master race doctrine, beer drunk from glass boots, Strength Through Joy? Where is the economic doctrine, the world view, the ideology? The answer, already indi- cated, is that there is none, beyond the needs of the moment.

Mussolini started off, we know, as a

Marxist indeed, as editor-in-chief of the socialist party daily Avanti! — young Be- nito was the foremost Italian Marxist theoretician of his time, and, had the first world war not happened along, he would doubtless be remembered as one of the leading Marxist revisionists of the century. But international proletarian brotherhood, he noticed, did not survive the first call-up papers — when the guns began to shoot a Worker was a German, a Frenchman or an E. nglishman first.

The revolution, Benito reasoned, would therefore have io take a patriotic form, the Whole oppressed nation against the inter- national plutocrats. A reading of La Psychologie des Foules by Gustave Le Bon Persuaded him that a man sprung directly from the crowd, an orator of commanding Personality and persuasive rhetoric, was needed to ignite the revolution and lead the nation to its destiny. In the mirror one morning he spotted just the chap for the job. His revolutionary party spontaneously organised itself, as officers back from the War formed themselves into fasci di com- battimento, fighting groups, to beat up combat-shy socialists and inadvertently give the world a new form of politics.

Adolf was also a keen reader, and a marked copy of Crowd Psychology by the British writer William MacDougall was found in his library in Berchtesgaden. He was not, however, any kind of Marxist but more of a Social Darwinist who thought that all 'history was the history of the struggle of races, with Aryans led by Germans bound to come out on top or nowhere. A glance at Italian history showed that there was no Italian race, and what impressed Adolf about his mentor was not his racial traits, or even his wardrobe, but the filet that he had got himself more or less legally into power in 1922 after a raggle-taggle March on Rome in which the Duce himself had prudently taken no part — although, as it turned out, not a shot was fired.

Adolf himself was able to ponder these events while doing time for his far riskier part in the Munich Beer Hall Putsch, an attempt at an operatic military coup in Which he only managed to save his life by an infantryman's reflex, throwing himself bone-crushingly to the ground when the local police opened up with live ammuni- tion. Nattily tailored, full of praise for motherhood, he emerged from prison a changed man, 'Legality Adolf, with a vision of how to attain power by the ballot-box while pretending, in a blaze of publicity, to be staging a bloody revolu- tion. Helped by the depression, he made his march on Berlin by Mercedes-Benz.

Sorcerer and apprentice were not, as it turned out, much practical use to each other. Benito could not have cared less about living space in the East, although he did send three divisions to Russia to show willing, while Adolf was a little more co-operative in providing five for Mare Nostrum, but not, in the end, to any better effect. It was as fellow-craftsmen that they admired each other to the end. Their craft was politics, and it is among politicians that we should look for their true heirs and successors.

Readers are of course free to check their own favourites, but lecteurs paresseux may prefer to see an independent marking. Adolf and Benito, as the old firm, natural- ly get 10 apiece. Sir Oswald Mosley gets 10 (perhaps 91/2 for not being all that obscure to begin with). Colonel de La Rocque of the prewar Croix de Feu scores a good solid 9, with a bonus point for having invented `Patrie, Famille, Travaille', the Vichy regime's slogan for a nation that likes its mottoes in threes. Although he has been acclaimed as de La Rocque's successor, I cannot in good conscience give Captain Jean-Marie Le Pen more than 4 with a marginal notation, 'Must work harder on organisation.'

Turning to some celebrated double acts of our own time, Mrs Thatcher (thought you might ask!) scores no more than 1, way below a pass, and that only for being a woman sent by destiny to save the nation. Bossy, perhaps, but her whole approach jars on the genuine fascist. Fascists need money like everyone else and have been known to pass the time of day with the wealthy but the mercantile spirit and the warrior code simply will not mix (see T. S. Eliot sneering at 'profit and loss'). Mikhail Gorbachev looks like our first duck, or Maggie's Drawers in the old military slang. (Do they still use that expression?) Unless I have missed his claiming to be sent by destiny, he seems to be working in the opposite direction, that is arguing that the Soviets' troubles have been caused by themselves and can only be remedied by the same people. '

Looking at men of the cloth, the Revd Ian Paisley gets 2 (unmasks Popish plot, Revd Ian sent by destiny to save the Province). His colleague the Ayatollah Khomeini, however, is good for at least a 9 and (have we seen him wearing' an armband of the Revolutionary Guards?) very likely to score 10 on a recount. His ploy of issuing international death warrants is one the Master himself never thought of, at least not officially.

The late Generalissimo Francisco Fran- co only gets 2. The Falange Party itself would do better, and it was the only legal political party in Franco's time, but the Caudillo was not its leader. General Hide- ki Tojo, Japan's Pearl Harbor Prime Minister, gets 2 (soldier, sent by destiny).

General de Gaulle gets the same, as does General Pinochet (the latter might just scrape a 3 for his New Chile). There is in fact a whole parade-ground full of military men barking orders who have come to power in coups, even possibly with fascist help, but still cannot pass as fascists. Real fascists tend to spring from the ranks, like Corporal Adolf and Private Benito.

Military success is not, however, a bar. Fidel Castro, if you care to check his paper, gets 10. The unnecessarily unifor- med Fidel says he is a Marxist, of course, and calls other people fascists. If we accept this we will have to invent a new term for people who preach Marxism in some here- tical form (but what is the true faith?) while behaving in the distinctive tion fascist style. General and Madam Chiang Kai-shek rate 5, Dr Francois and Mme Yvonne Duvalier, of Haiti, a promis- ing 7.

Comrade and Mme Mao Tse-tung share a 10 and rank as the world's first his-and- hers fascist dictatorship. The Great Helms- man did not claim the distinction, but see remarks above about disowning losers. Point by point, however: the teenage Red Guards, the conspicuous violence, the plot of Imperialists, Hegemonists, Confucians and Italian film directors, the Chairman's dubious athletic feats, the Little Red Book, all fit too neatly into the checklist to be accidental. Either we classify the Maos as a family dictatorship of the fascist type or we need a whole new political terminol- ogy to distinguish military strongmen and reformist communist leaders from dictators who have clearly, by their methods, hit on Adolf s secret. Which brings us to the fascinating case of Josef Stalin. The mystery man from Geor- gia who was so busy eliminating the hidden enemies of the State in the late 1930s, who so loved to review his white-shirted, red- scarved Young Pioneers (they still exist, with membership compulsory for every Soviet schoolchild), whose working dress changed, over the decades, from a peasant's smock to a white uniform spang- led with unearned medals — Uncle Joe must, even on a preliminary check, score very highly on a fascist test-paper. By coincidence, this year of Adolfs centenary we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Nazi-Soviet pact, the theoretically (as was claimed at the time) impossible embrace of fascism and communism. The event was so important, its consequences so appalling, that, getting both our dolefuranniversaries out of the way together, we might look at it next week.

Previous page

Previous page