BOOKS

Her spark doused forever

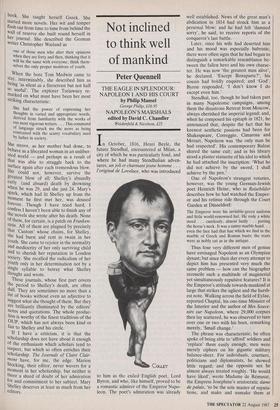

Paul Foot

THE JOURNALS OF MARY SHELLEY 1814-1844, PART 1 1814-1822 edited by Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert OUP, f55 From the moment Byron met Shelley in 1816, the two men argued. At the root of the argument was Shelley's belief in human perfectibility: the notion that humankind could and should be improved far beyond most people's wildest dreams. When the two men met again in Venice in 1818, and rehearsed the arguments, Shelley wrote a poem about it, 'Julian and Maddalo'. Julian puts the Shelley argument: We might be otherwise; we might be all We dream of, happy, high, majestical. Where is the beauty, love and truth we seek, But in our minds? And, if we were not weak, Should we be less in deed than in desire?' `Ay, if we were not weak — and we aspire, How vainly! to be strong,' said Maddalo. `You talk Utopia.'

The argument raged on, and pretty sharp it was too. But it is not resolved.

A close observer of this argument when it first broke out in 1816 was Mary Woll- stonecraft Godwin, then 18, who had eloped with Shelley two years earlier. While the two geniuses argued away in the Swiss mists, the teenager wrote a story about a man created by another. The story became more popular by far than any of the most popular works written by either Byron or Shelley, and (unlike anything either of the poets ever wrote) entered deep into the imagination of many millions of people all over the world.

Was it just a horror story, this Franken- stein? Or was it an allegory which flowed directly from the argument which raged about its author as she wrote it?

Reactionaries, who for some reason have always made common cause with Mary Shelley (she married Shelley after his first wife committed suicide later that year, 1816) have been quick to interpret Dr Frankenstein as Shelley himself, playing with revolutionary ideas which were bound to turn against him. They miss the whole point of the story. The monster himself is not naturally violent, or even anti-social. All his instincts are kindly, humble, co- operative. He is also exceptionally clever, and has fantastic physical prowess. It is only because he seems ugly and monstrous that people shun him. He needs his creator to explain his origins to the human race. But Dr Frankenstein has deserted him. This desertion is what finally drives the monster to violence and destruction.

Everything written or spoken by Mary Shelley in her journals or anywhere else before she wrote Frankenstein suggests she was firmly on Shelley's side in the argu- ment with Byron. She too was for the perfectibility of the human race; for the highest possible revolutionary aspirations.

What worried her was the level of commit- ment of wealthy or well-born revolution- aries who played with revolutionary ideas, only to abandon them as soon as they were successful. A revolution abandoned by the brilliant men and women who helped to set it in motion, she believed, was doomed.

With all this, Shelley agreed. Indeed, he was the first to be struck with the signifi- cance and the excellence of Mary's novel. He fought against her modesty, and per- suaded her to revise it and prepare it for publication. In the first volume of these journals, which they kept together, there is plenty of evidence on both sides of the grand egalitarian love affair in which they were engaged. 'She feels as if our love would alone suffice to resist the invasions of calamity,' wrote Shelley. Mary testified to this again and again. 'Sunday 30th October, 1814. Talk with Shelley all day.' `6th November, 1814. This is a day devoted to love and idleness.'

In January 1815 she wrote to Shelley's friend, Jefferson Hogg: 'I who love him so tenderly and entirely, whose life hangs on the beam of his eye and whose whole soul is entirely wrapped up in him . .

This was not conventional romantic love, which both scorned. It was a meeting of ideas, a blending of intellectual and physical attraction. In the summer of 1817, Shelley paid tribute to it in his dedication to Mary of 'The Revolt of Islam':

Thou friend, whose presence on a wintry heart Fell like bright spring upon a herbless plain, How beautiful and calm and free thou wert In thy young wisdom, when the mortal chain Of Custom thou didst burst and rend in twain. And walk as free as light the clouds among . . .

After the First Journal, which is full of this passion and mutual intellectual re- spect, Shelley drops out. Mary continues in a more subdued and repetitive tone to chronicle her way through the ordeals which tormented the love affair for the next five years. In 1818, their daughter Clara died, aged two, in Venice. Their beloved Willmouse, aged five, died the following year. The sad little Shelley caval- cade shifted restlessly across Italy, and Mary had somehow to cope with the complicated domestic arrangements, and above all with the non-paying guests.

Claire Clairmont, her step-sister, who had managed to accompany Shelley and Mary even on their elopement, was always there or thereabouts, to Mary's increasing irritation. Claire has since been rescued as a woman in her own right by Richard Holmes's magnificent biography of Shelley and by Marion Stocking's edition of her journals. But Mary couldn't stand her. Her indignation with Claire's constant claims on Shelley's affections and concerns keeps breaking out in the Journals.

`June 8, 1820: A better day than most and good reason for it . . . C away at Pungnano.'

If she wasn't being irritated by Claire there was certain to be another begging letter from her father, the querulous hypocrite, William Godwin.

The grand love affair of 1814 to 1817 was badly bruised by all this, of course, and Shelley played his part in the bruising. The dream of women's liberation as an idea, when read in youth in the pages of Mary's mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was tar- nished in real life, with real babies to look after and real households to manage. On 18 June, 1822, six weeks before he died, Shelley wrote to a friend:

It is the curse of Tantalus that a person possessing such excellent powers and so pure a mind as hers [Mary's] should not excite the sympathy indispensable to their application to domestic life.

This was a far cry from the uncritical adulation of the early years. 'Domestic life' had not even been anticipated in that rapturous dedication of 'The Revolt of Islam'.

The wonder, however, is not so much that the love affair lost its glitter after years of drudgery and grief — what love affair does not? The wonder is that this extraor- dinary woman rose above all these difficul- ties. She kept up her prodigious self- education, matching even Shelley book for book. She taught herself Greek. She started more novels. Her wit and temper flash out from time to time from behind the wall of reserve she built round herself in her journal. She described the German writer Christopher Wieland as

one of those men who alter their opinions when they are forty and then, thinking that it will be the same with everyone, think them- selves the only proper monitors of youth.

When the bore Tom Medwin came to stay, interminably, she described him as being 'as silent as a firescreen but not half so useful'. The explorer Trelawney re- marked on what must have been her most striking characteristic:

She had the power of expressing her thoughts in varied and appropriate words, derived from familiarity with the works of our most vigorous writers . . . This command of language struck me the more as being contrasted with the scanty vocabulary used by ladies in society.

She strove, as her mother had done, to behave as a liberated woman in an unliber- ated world — and perhaps as a result of that was able to struggle back to the surface again after each tremendous blow. She could not, however, survive the greatest blow of all: Shelley's absurdly early (and absurd) death by drowning When 'he was 29, and she just 24. Mary's spark, which had lit Shelley up from the moment he first met her, was doused forever. Though I have tried hard, I confess I haven't been able to finish any of the novels she wrote after his death. None of them, for certain, is a patch on Franken- stein. All of them are plagued by precisely that 'Custom' whose chains, for Shelley, she had burst and rent in twain in her Youth. She came to rejoice in the normality and mediocrity of her only surviving child and to cherish her reputation in London society. She recalled the radicalism of her youth only in her determination not by a single syllable to betray what Shelley thought and wrote.

These journals, whose first part covers the period to Shelley's death, are often dull. They are sometimes no more than a list of books without even an adjective to suggest what she thought of them. But they are brilliantly illuminated by the editors' notes and quotations. The whole produc- tion is worthy of the finest traditions of the OUP, which has not always been kind or fair to Shelley and his circle. If I have a criticism, it is that the scholarship does not have about it enough of the enthusiasm which scholars tend to suspect, but which so often enriches their scholarship. The Journals of Claire Clair- mont have, for me, the edge. Marion Stocking, their editor, never wavers for a moment in her scholarship, but neither is there a shred of doubt of her admiration for and commitment to her subject. Mary Shelley deserves at least as much from her editors.

Previous page

Previous page