A mosaic of wit, vanity and irritability

Miron Grindea

PAST TENSE: THE DIARIES OF JEAN COCTEAU: VOLUME II annotated by Pierre Chanel, translated by Richard Howard

Methuen, £18.50, pp.350

Jean Cocteau remains, 30 years after his death, an irritant among his detractors, who are still many. All his life he was accused of being a dancing Octopus, a Jack-of-all-trades, a touche-et-tout, and be- cause of his ability to impart a refreshing vitality to much that he touched, most of his exploits, no matter how much pure gold he mined during his voyages, were re- ceived — particularly in Parisian circles as mere clever juggling.

A creator without frontiers, this spoilt child who had enchanted three genera- tions, had been galloping in all directions, covering almost every aspect of artistic expression — poetry, painting, theatre and stage design, the cinema and music, murals and prints — always carried away by waves of metaphor. Never losing his grip on the tools he was toiling with, he yielded to none of them.

From the beginning Cocteau introduced autobiographical chunks into his prose (Opium, Journal d'une desintoxication, Journal d'un film, Retrouvons notre en- fance, Tour du monde en 80 jours), but it was during the last 12 years of his life that he kept a regular diary, destined to appear only after he had gone. (II faut vivre posthume,' he wrote, forgetting what he had said in 1912, 'I can hardly wait to become famous.') Two eminent literary historians, Jean Touzot and Pierre Chanel, have now embarked upon the daunting task of putting some order in the vast Coctelian heritage, but this may well take us into the third millenium, when a new George Painter might perhaps emerge. The first two volumes of Past Tense (Le passe defini), covering the years 1951- 1953, do little to dispel the image of the same unclassifiable seducer who would usually end by combatting his own self- provocations and spiritual debaucheries. (There was no exaggeration in what the poet said in Le secret professionnel 'from birth my cargo has been badly stowed and I have never stood still'.)

After those aberrant revelations of most entries written during the Nazi occupation

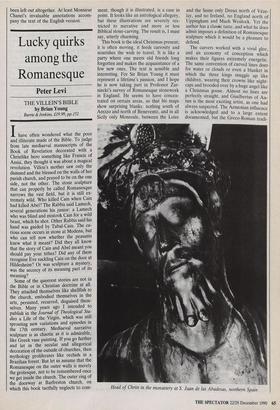

of France, which stunned and repelled all Cocteau's friends, and which culminated in his hero worship of Hitler, the poet and saviour of humanity, one eagerly awaited some edifying clues to the poet's inner life, but all that one gets in these latest disclo- sures is once again a mosaic of wit, vanity and irritability. His reflections on complet- ing a commissioned painting: 'I am so fond of my picture' (Mere et fille dans un jardin) that I would like to forget I painted it and be rich enough to buy it.' Similarly, he was convinced that one of his tapestries exhi- bited at the Antibes Museum surpassed in inventiveness Picasso's works. He dismis- ses practically all of his fellow-writers, who, he thinks, no longer know the lan- guage. Claudel and Giraudoux are 'the two disastrous victors of our age'. The vulgarity of Anouilh: Most of his works would shame me to death if I had written them.' La Cocteau's portrait of Ezra Pound condition humaine is a 'detestable' work, and most of those considered as 'the great French writers', Malraux, Camus, even Sartre, are 'mere journalists'.

For all his immense nervous energy, brilliance and sophistication he was vulner- able, bitter, volatile, insecure. He always wanted to be liked — that's why he never said no whenever he was asked to write a preface, do a poster or give a lecture.

As he was in no doubt that one day the diaries would see the light, he self- mockingly anticipated the contradictions and inconsistencies which future readers would stumble upon. The only excuse he could invoke was that he could never find a moment to check on what he jotted down at a given time. In Gide Vivant (1951), he accused his tortuous enemy-friend of a multiplicity of lies on which his famous Journal was built, but he somehow forgot his life-long boutade: 'I lie to tell the truth.' And yet, behind the histrionics, he seems to have really been afflicted by what he described as the difficulte d'être, 'A hun- dred years after my death I'll rest comfort- ably.' As to his fame, if not the gloire, 'it surpasses my work which should rejoin my name.' Constantly, he was directly re- sponsible for so many self-inflicted in- juries. 'It's a great joy to love the work of an enemy', he admits when referring to Andre Breton's novel, Nadja. In a letter to Tzara, while agreeing that 'Cocteau hasn't done me any harm and hatred is not my forte', Breton insisted that, all the same (sic!) he is '!'titre le plus haissable'; and when another militant surrealist, Paul Eluard, decided 'we will ultimately succeed in breaking him like a stinking beast', Cocteau, with his sense of drama, seized upon the occasion to compare his life to that of Rousseau, at the time the author of Confessions was hunted by the Encyclo- paedists.. .

Writing in 1959, Cocteau little realised that only seven years later he would be, once again, savagely attacked by Breton. Indeed, when, in 1960, at the death of the 87-year-old Paul Fort, he was designated by a sizeable group of literary figures to succeed Fort as 'prince des poetes' , there emerged within hours an anti-Cocteau front at the Café Fiore and Aux Deux Magots. This proved to be more vitriolic than anything one could have imagined possible in the Montparnasse area. Breton, still the undisputed Pope of Surrealists, inspired an army of snipers installed on the two formidable literary fortresses and he succeeded.

The diaries end with a genuinely felt (Ti de coeur, over Jeannot's 'incomprehensible character'. Jean Marais, the film star who often proclaimed that he was Cocteau's creation, 'comes in unexpectedly, trips over Ansam, the dog, kicks him and yells'. Like any dependent lover, the injured host tried to console himself by conceding that, after all, `Jeannot adores me but never believes a word I say; I never manage to convince him and this is one of my greatest heartaches'. However, there was no time to pine; he had to return to Paris to resume work on his next film. 'I'll rehearse the Sphinx scenes tonight'.

Richard Howard has for years been one of the most industrious translators from the French, but Cocteau's scintillating imagery eludes him. More often than not, one has to reach for the Gallimard original and make up for a great many missing pas- sages, omitted for no reason. On a person- al note I wonder what could have moved Mr Howard, himself a poet, to suppress this delightful quatrain Que serait un Adam sans Eve?

(Eden et solitude aidant) Eve serait d'Adam le reve

Peut-titre un poi me d'Adam.

As to the Annexes (40 pages), they have been left out altogether. At least Monsieur Chanel's invaluable annotations accom- pany the text of the English version.

Previous page

Previous page