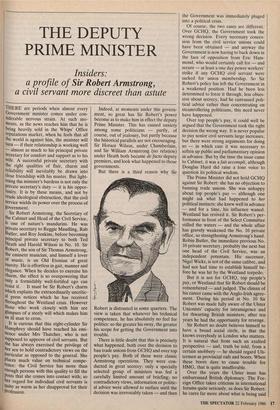

THE DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER

Insiders:

a profile of Sir Robert Armstrong,

a civil servant more discreet than astute

THERE are periods when almost every Government minister comes under con- siderable nervous strain. At such mo- ments, as the news reaches him that he is being heavily sold in the Whips' Office reputations market, when he feels that all the world is against him, the minister will turn — if their relationship is working well — almost as much to his principal private secretary for comfort and support as to his wife. A successful private secretary with the right qualities of flair, charm and reliability will inevitably be drawn into close friendship with his master. But light- ening the minister's burdens is not only the Private secretary's duty — it is his oppor- tunity. It is by these means, and not by Crude ideological obstruction, that the civil service wields its power over the process of government.

Sir Robert Armstrong, the Secretary of the Cabinet and Head of the Civil Service, Is one of nature's mandarins. He was Private secretary to Reggie Maudling, Rab Butler, and Roy Jenkins, before becoming Principal private secretary to both Ted Heath and Harold Wilson in No. 10. Sir Robert, the son of Sir Thomas Armstrong, the eminent musician, and himself a lover of music, is an Old Etonian of great suavity. He is effortless in gait, manner and elegance. When he decides to exercise his charm, the effect is so overpowering that only a formidably well-fortifed ego can resist it. It must be Sir Robert's charm which explains the extraordinarily uncritic- al press notices which he has received throughout the Westland crisis. However those who work closely with him see glimpses of a steely will which makes him an ill man to cross.

It is curious that this eight-cylinder Sir Humphrey should have reached his emi- nence under Mrs Thatcher, who is not supposed to approve of civil servants. But she has always exercised the privilege of her sex to hold contradictory views on the Particular as opposed to the general. She Places much value on technical compe- tence: the Civil Service has more than enough persons with this quality to fill the Posts that she comes into contact with; so her regard for individual civil servants is quite as warm as her disapproval for their Profession. Indeed, at moments under this govern- ment, so great has Sir Robert's power become as to make him in effect the deputy Prime Minister. This has caused anxiety among some politicians — partly, of course, out of jealousy, but partly because the historical parallels are not encouraging. Sir Horace Wilson, under Chamberlain, and Sir William Armstrong (no relation) under Heath both became de facto deputy premiers, and look what happened to those governments.

But there is a third reason why Sir Robert is distrusted in some quarters. The view is taken that whatever his technical competence, he has absolutely no feel for politics: so the greater his sway, the greater his scope for getting the Government into trouble.

There is little doubt that this is precisely what happened, both over the decision to ban trade unions from GCHQ and over top people's pay. Both of these were classic Armstrong operations. They were con- ducted in great secrecy: only a specially selected group of ministers was fed a carefully limited amount of briefing; no contradictory views, information or politic- al advice were allowed to surface until the decision was irrevocably taken — and then the Government was immediately pluged into a political crisis.

Of course, the two cases are different. Over GCHQ, the Government took the wrong decision. Every necessary conces- sion from the civil service unions could have been obtained — and anyway the Government is now having to back down in the face of opposition from Eric Ham- mond, who would certainly call for — and secure — at least a one day power workers' strike if any GCHQ civil servant were sacked for union membership. So Sir Robert's policy has left the Government in a weakened position. Had he been less determined to force it through, less obses- sive about secrecy, had he canvassed poli- tical advice rather than concentrating on steamrollering politicians, this need never have happened.

Over top people's pay, it could well be argued that the Government took the right decision the wrong way. It is never popular to pay senior civil servants large increases, but there were strong arguments for doing so — in which case it was necessary to soften up public and parliamentary opinion in advance. But by the time the issue came to Cabinet, it was a fait accompli, although Douglas Hurd did raise a lone voice to question its political wisdom.

The Prime Minister did not hold GCHQ against Sir Robert: she has no objection to banning trade unions. She was unhappy about top people's pay — although one might ask what had happened to her political instincts: she knew well in advance — and for a time, his influence waned. Westland has revived it. Sir Robert's per- formance in front of the Select. Committee stilled the waters — and the whole affair has gravely weakened the No. 10 private office, so strengthening Armstrong's hand. Robin Butler, the immediate previous No. 10 private secretary, probably the next but one head of the Civil Service, was an independent potentate. His successor, Nigel Wicks, is not of the same calibre, and had not had time to establish himself be- fore he was hit by the Westland torpedo.

But it is not for GCHQ, top people's pay, or Westland that Sir Robert should be remembered — and judged. The climax of his career came with the Anglo-Irish agree- ment. During his period at No. 10 Sir Robert was made fully aware of the Ulster Unionists' capacity for intransigence and for thwarting British ministers; after ten years he had the opportunity for revenge.

Sir Robert no doubt believes himself to have a broad social circle, in that the knows everybody in London who matters. It is natural that from such an exalted perspective — and, truth be told, from a certain snobbery — he should regard Uls- termen as provincial oafs and boors. When these boors dare to cause trouble for HMG, that is quite insufferable.

Over the years the Ulster issue has embarrassed British diplomacy. The For- eign Office takes criticism in international forums quite seriously, as does Sir Robert: he cares far more about what is being said at some UN committee on human rights than about the views of Ballymena or Ballymoney.

Sir Robert, of course, regards Ulster Unionists as the prisoners of ludicrous prejudices. Who in this day and age can take religion seriously or indulge in such blatant expression of nationalist senti- ment? He does not realise that in his dealings with the Unionists, he is at least as much a captive of his prejudices — stan- dard metropolitan 1960s — as they are of theirs.

But he has managed to convince his masters, and they have not. If only the present Unionist leaders had a little of his savoir-faire and grace of address — if only one could be sure that he had some of their strongly forged loyalty and love of country rooted in the blood and soil.

Sir Robert was able to work on the Prime Minister's profoundly un-Tory im- patience with talk of insoluble difficulties and on her conviction that all a problem needs is a little touch of Maggie. He and the Foreign Office concealed from her their belief in Irish unity as the ultimate solution. He was able to persuade British ministers of John Hume's argument that the Unionists needed to be made to face reality. They did not realise that Mr Hume's view is only 'a more sophisticated variant of the age-old desire of the two Ulster communities to score off one another, and that to concede to it, far from reducing tension, stokes it up.

Most senior civil servants come to be- lieve that politics is the pleasure principle, administration the reality principle. Sir Robert Armstrong's entire career in the public service is an expression of that view. But despite his abilities, his record illustrates the dangers of dispensing with politics.

Previous page

Previous page