Exhibitions

Wright of Derby (National Gallery until 27 April)

Derby's day

David Wakefield Some 15 or 20 years ago Joseph Wright `of Derby' was virtually unknown except to a small group of local enthusiasts. After the publication of the late Benedict Nicol- son's monumental book on the painter in 1968, this state of affairs gradually changed as owners, increasingly aware of the value of their possessions, consigned paintings by Wright to the salerooms where prices have soared dramatically. The latest event in this development was the sale at Christie's in 1984 of the group portrait of Mr and Mrs Thomas Coltman and its subsequent ac- quisition by the National Gallery. There it now forms the core of a small exhibition, devoted to this and other related paintings by the artist borrowed from public and private collections. At last, it seems, Wright has acquired that aura of metropo- litan smartness which he shunned through- out his life, preferring to remain the robust, down-to-earth, slightly cantanker- ous Midlander which emerges in so many of his best portraits. Unlike his fashionable counterpart Reynolds, Wright refused to flatter his sitters with idealised versions of themselves; instead he shows his women like Catherine Swindell and Sarah Carver not as beautiful but astonishingly lifelike, with their double chins and strong coarse features. Here, in the sanctum of the National Gallery, Joseph Wright has re- tained his tag 'of Derby', and rightly so, for he still belongs unmistakably to his native town and county with its population of doctors, amateur scientists, lawyers and modest country squires whose features figure so prominently in his work. In the early 1770s, when the portrait of `Mr and Mrs Coltman' was painted, Derby was a compact, early industrial town of 9,000 inhabitants, full of decent red-brick Georgian houses, adorned only by the occasional Venetian window and decora- tive fanlight. Most of this, of course, has been swept away by progressive modern planners. But just enough survives to enable us to visualise what life was like at that time, when small groups of intelligent, like-minded men met in each other's houses to discuss the latest events in science and philosophy. A further advan- tage of life in the 18th century was that towns preserved a close link with the surrounding countryside; there was no sea of encircling suburbia, only green fields, spruce hedgerows and red-brick farm-

houses. Both Wright and his friends and patrons the Coltmans lived in the town. At weekends the painter used to set out on foot to visit other patrons living in nearby country houses; further afield he explored the wild and remote parts of the Peak District.

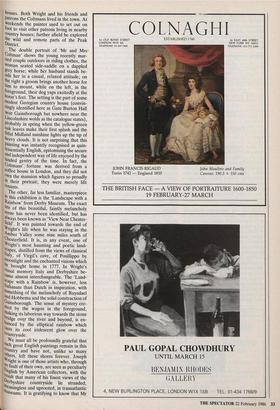

The double portrait of 'Mr and Mrs• Coltman' shows the young recently mar- ried couple outdoors in riding clothes, the woman seated side-saddle on a dappled grey horse; while her husband stands be- side her in a casual, relaxed attitude; on the right a groom brings another horse for him to mount, while on the left, in the foreground, their dog yaps excitedly at the horse's feet. The setting is the part of some Modest Georgian country house (convin- cingly identified here as Gate Burton Hall near Gainsborough but nowhere near the Lincolnshire wolds as the catalogue states), probably in spring when the yellow-green oak leaves make their first splash and the fitful Midland sunshine lights up the tip of heavy clouds. It is not surprising that this Painting was instantly recognised as quin- tessentially English, epitomising the secure and independent way of life enjoyed by the landed gentry of the time. In fact, the Coltmans' fortune was derived from a Coffee house in London, and they did not own the mansion which figures so proudly in their portrait; they were merely life tenants.

The other, far less familiar, masterpiece in this exhibition is the 'Landscape with a Rainbow' from Derby Museum. The exact Site of this beautiful, faintly melancholy Scene has never been identified, but has always been known as 'View Near Chester- field'. It was painted towards the end of Wright's life when he was staying in the Amber Valley some nine miles south of Chesterfield. It is, in any event, one of Wright's most haunting and poetic land- scapes, distilled from the views of classical Italy, of Virgil's cave, of Posillippo by ILlloonlight and the enchanted visions which ue brought home in 1777. In Wright's visual memory Italy and Derbyshire be- came almost interchangeable. The 'Land- cape with a Rainbow' is, however, less Italianate than Dutch in inspiration, with something of the melancholy of Ruysdael and Hobbema and the solid construction of 0ainsborough. The sense of mystery cre- ated by the wagon in the foreground, Iillaking its laborious way towards the stone tLridge over the river and beyond, is en- 'lanced by the elliptical rainbow which casts its cool iridescent glow over the countryside. We must all be profoundly grateful that such great English paintings remain in this country and have not, unlike so many others, left these shores forever. Joseph Wright is one of those artists who, through no fault of their own, are seen as peculiarly

English by American collectors, with the

result that many of his finest views of the uerbyshire countryside lie stranded, meaningless and uprooted, in transatlantic museums. It is gratifying to know that Mr and Mrg Coltman will stay here for good, but might it not be even better if they could be reunited (if only temporarily) with their fellow citizens Dr Darwin, Jedediah Strutt, the Revd d'Ewes Coke and all those other local worthies painted by Wright who still, fortunately, remain in their native town?

Previous page

Previous page