ARTS

Music 1

Schumann's last, lost variation

Louis Jebb

he discarded work of artists, writers and composers is often best left alone. Even the brightest genius cannot produce day in and day out something worth publishing or hanging. Robin Holloway discussed this point last month (24 June) in relation to recent Britten revivals, but with the composer Robert Schumann it has often been the works discarded by his heirs that have interested scholars more than his acclaimed masterpieces. Most amusing was the case of his violin concerto, written for Joseph Joachim in 1853, but scorned by Joachim as not up to the master's highest standards and excluded from publication by Johannes Brahms and Schumann's widow, Clara.

In March 1933, during a game of ouija, Joachim's great-niece Jelly d'Aranyi, her- self a top-flight violinist, received a mes- sage from Schumann asking her to find and perform an unpublished work of his for violin. Tracing the manuscript to Berlin, she achieved — despite the opposition of both the German government and Schu- mann's surviving 86-year-old daughter, Eugenie — the publication of the concerto in 1937 and the first British performance in February 1938. But, in spite of her long strug- gle, the work was faintly scorned by the critics (with Donald Tovey a noteworthy exception) and has never entered the mainstream repertoire.

Recently a manuscript has come to light which reopens the case on another com- position largely suppressed by Brahms and Clara Schumann. The piece, a Thema and variations for piano in E flat, has been the source of much interest because it was written by Schumann at the time of a psychotic collapse in February 1854, which

led to the end of his composing career.

During a chronic bout of tinnitus on 17 February 1854, Schumann heard a tune in his head, dictated (depending on the ver- sion of the story) by angels or by a combination of Schubert, Beethoven and Mendelssohn. In the succeeding days, in his lucid moments, Schumann wrote varia- tions on the theme at his house in Dussel- dorf, but on 27 February, the day he was making a fair copy of the variations, he threw himself into the Rhine and had to be rescued by watching fishermen. Schumann spent the remaining two years of his life in an asylum, composing no more, and it has always been assumed that the variations were never completed.

At the time of Schumann's collapse, two of his young protégés, Joachim and Brahms, rushed to Clara's aid. The 21- year-old Brahms stayed near Clara for two years, helping with the household and her seven children, and with the preparation of

an edition of her husband's music. It was the beginning of a memorable romantic friendship. Given the work's connection to the traumatic events that brought them together, Brahms's and Clara Schumann's attitude to Schumann's final composition was an intriguing one. It was deemed unworthy and, at first, excluded from the edition. However, Brahms wrote and pub- lished his own variations on the Thema and then, in 1893, published the Thema proper in a supplementary volume of Schumann's work. But the variations, the product of the days when Schumann was gradually losing control of his mental faculties, re- mained unpublished following Clara's death in 1896 and Brahms's in the follow- ing year.

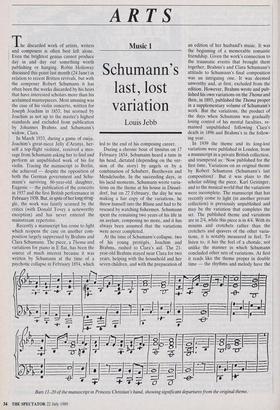

In 1939 the theme and its long-lost variations were published in London, from a manuscript in a private British collection, and trumpeted as: Now published for the first time, Variations on an original theme by Robert Schumann (Schumann's last composition)'. But it was plain to the scholar editing the piece, Karl Geiringer, and to the musical world that the variations were incomplete. The manuscript that has recently come to light (in another private collection) is previously unpublished and may be the variation that completes the set. The published theme and variations are in 2/4, while this piece is in 4/4. With its minims and crotchets rather than the crotchets and quavers of the other varia- tions, it is notably measured in feel. To listen to, it has the feel of a chorale, not unlike the manner in which Schumann concluded other sets of variations. At first it reads like the theme proper in double time — the rhythms and melody have the Bars 11-20 of the manuscript in Princess Christian's hand, showing significant departures from the original theme. same pattern — but there are decorations and numerous small variations in rhythm, and the chord patterns are a combination of those in the theme proper and those in the published variations. But the manuscript is a perplexing one. Firstly, it is not in Schumann's hand. The hand is that of Queen Victoria's daughter Princess Helena, Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein, noted in her day as a `musical' royalty, a familiar of Joachim and, almost certainly, of Clara Schumann. Second, the princess has dated the manu- script 1897 and headed it 'Thema' and 'unpublished, by Robert Schumann'. Yet the Thema was published in 1893, and the piece she has written out is not the Thema. Third, the manuscript has a number of glaring wrong notes and solecisms in musical notation. And here the experts are divided. Either the princess had heard the Thema and misremembered it, writing down a corrupt version. Or she was given by Clara, or one of her circle, an extra variation on the Thema, which was indeed unpublished in 1897 and remains so today. And, in that case, the solecisms are a feature of Schu- mann's mental disintegration. It is tempting to lean to the side of safety and admit a corrupt remembrance by an amateur musician. And yet, given the passionate background to the case, that seems to me an approach to history that always dates a house too late, or says that something did not happen because it 'would not have happened'. Furthermore, the provenance of the manuscript is a strong one. It was found among the papers of a descendant of Princess Christian's protegee, Emily Shinner, a professional violinist and a pupil of Joachim, and a good friend of Clara Schumann. Through her patron, Miss Shinner met and married Augustus Liddell, formerly ADC to the Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton. As Emily was a 'professional woman' Liddell was forced to resign his commission in the Royal Horse Artillery. Incensed at this, Queen Victoria made Liddell one of her Gentlemen-at-Arms, and his sister Gerry (herself a pupil of Clara Schumann and later secretary and general factotum to the Joachim quartet on their European tours), a lady-in-waiting. Subsequently, Liddell became Comptroller of Prince and Princess Christian's household. It was pre- cisely the type of enthusiastic circle into which Clara Schumann, Brahms or Joachim might have introduced a scrap of music which they always thought would remain ephemeral. The' published variations and this troublesome new manuscript are archetyp al products of Schumann's last, morbid, Period. The theme itself is a haunting one; and there are some glorious transitions mixed in with less exciting passages. Audi- ences were given a chance to judge the manuscript with public performances on 10 and 17 July given, respectively, by Steuart Bedford and Jenni Wake-Walker at 37 Charles Street, now the headquarters of the English-Speaking Union, a house where Clara Schumann herself, the pre- eminent pianist of her age, once performed at one of Mrs Edward Baring's private concerts in February 1882. Whatever the morality of reviving the works discarded by the guardians of an artist's reputation, both Mr Bedford's and Mrs Wake-Walker's playing convinced this listener, for one, that here was Schumann's final work, complete at last, and as well worth reviving as his unjustly neglected violin concerto.

Audio and video transcriptions of the 10 July performance are on sale for the benefit of the National Art-Collections Fund and the English-Speaking Union. Write to Louis Jebb, do The Spectator.

Previous page

Previous page