SPECTATOR SPORT

Majestic in his madness

Simon Barnes

THE vulnerability of Steve Redgrave; the heat of the British summer; the reliability of racehorses; the strength and depth of British tennis. The sporting year seems to have been structured around the indomitability of Redgrave. He was a mira- cle we were preparing to celebrate on schedule, halfway through the Olympic Games in September. Redgrave has already done the impossible. He has won a gold medal at four successive Olympic Games. He is a titanic oarsman with a diamond-hard competitive will; an enig- matic giant comprised of nothing but talent. His ruthlessness towards himself is matched only by his ruthlessness towards his opponents. Four years ago, as the British pair was about to compete in a major event amid rumours that Redgrave was over the hill, he muttered to his part- ner, Matthew Pinsent, at the start, `Let's crush some dreams.'

Redgrave famously said in victory at the last Olympics that anyone who saw him in a boat again had full permission to shoot him. But he unretired almost at once and set out for a tilt at the impossible fifth — this time in a four. And he has rowed from victory to victory, just as we would expect. But then, last weekend, at last and impossibly, Redgrave showed signs of frailty, vulnerability, humanity. The four was narrowly beaten in the semi-finals of a World Cup event. That was a setback; the final was humiliation. They were beaten into fourth place.

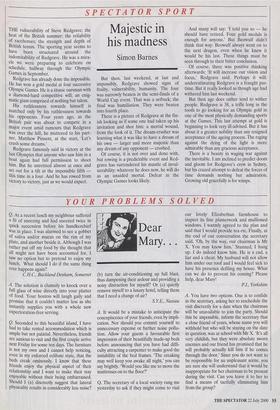

There is a picture of Redgrave at the fin- ish looking as if some one had taken up his invitation and shot him: a mortal wound, from the look of it. The dream-crusher was learning what it was like to have a dream of his own — larger and more majestic than any dream of any opponent — crushed. Of course, it is not over and done with, but rowing is a•predictable event and Red- grave has surrendered his mantle of invul- nerability: whatever he does now, he will do as an unaided mortal. Defeat in the Olympic Games looks likely. And many will say: `I told you so — he should have retired. Four gold medals is enough for anyone.' But Beowulf didn't think that way: Beowulf always went on to the next dragon, even when he knew it would be his last. These things must be seen through to their bitter conclusion.

Of course, there was positive thinking afterwards: `It will increase our vision and focus,' Redgrave said. Perhaps it will: underestimating Redgrave is a fraught pas- time. But it really looked as though age had withered him last weekend.

But then age does rather tend to wither people. Redgrave is 38, a trifle long in the tooth to go looking for an Olympic gold in one of the most physically demanding sports at the Games. This last attempt at gold is beginning to look very ill-advised. But it has about it a greater nobility than any resigned acceptance of the ageing process. The raging against the dying of the light is more admirable than any gracious acceptance.

There is a beauty in waging war against the inevitable. I am inclined to predict doom and gloom for Redgrave's crew in Sydney, but his crazed attempt to defeat the forces of time demands nothing but admiration. Growing old gracefully is for wimps.

Previous page

Previous page