LIFE AMONG THE RUINS

Gerda Cohen on the

relics of the Black Country's traditional trades

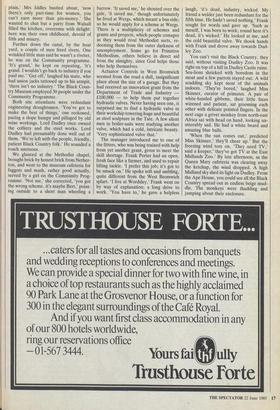

UNDER a scudding sky, the Black Coun- try turned out beige, and quite clean. This was somewhere between Tipton and Dud- ley, an endless twining muddle of works and shed and works and housing with tiny frozen back gardens, scrubbed brick Methodist chapels, pie shops and factory chimneys. No smoke came out of the chimneys. 'They're gone, shut,' Bill Allen laughed pleasantly, 'the works are gone.' He wore a neat zip jacket and laughed a great deal, like a sad intelligent horse. 'If you haven't seen a foundry, Victor Cast- ings will amuse you.'

Victor Castings turned out to be archaic, though beautiful in a way, a spread of fire and murk and vapour, with short men in side-whiskers thudding about, and globs of molten metal jumping out of the furnace. Away from the furnace it was freezing cold and stank of sulphur and coke. 'The men start at six,' Bill shouted over the din, 'they're 40-year men, been here 40 years.' He introduced me to Levi, who made chain spikes to put round pubs. Levi had beigey- white whiskers growing over much of his face, and amazingly white hands. 'Work never hurt nobody,' he examined his palms in a pious manner. Levi's son and wife also worked here. If the foundry went bank- rupt, would they find another job? Bill considered: 'It's a moot point.' He said there was an extreme shortage of skilled labour, even now: `I'm not talking about computer engineers, I mean a shortage of toolmakers, die turners, your traditional Black Country trades. The old apprentice system has broken down, and it's getting worse.'

Bill seemed oblivious of the frightful cold and clangour. 'I needed a toolmaker so I rang a chappie I know is unemployed — not worth his while! Better off on the dole.' Leaving me to digest this, Bill walked over the frozen grit to a lot of dented buckets containing iron shapes. 'Guess what? Carpet clips for Belgium.' A couple of glum youths were pitching clips into a shot-blasting machine. 'He's off the dole,' said Bill, 'young chappie with the ear-ring.' Dudley had 23,000 on the regis- ter that month; surely people wanted work? 'Some do,' remarked Bill, 'I think the dole is too easy.'

Next door the women sorters chatted, skittering with laughter. 'Gwen Bradnick, known as the ferret, and Hazel.' Hazel had a worn, queenly expression; she started here aged 13. 'You had to them days.' Her skin was still lovely, creased like an old camellia. Gwen the ferret darted about teasing everyone till they shrieked. 'You've got to laugh, haven't you? Levi's wife hammered at iron shapes. They were hurricane hinges, for Bermuda. How did Victor Castings land such an export? 'Old family connections,' said Bill, and drove to the Black Country Museum. A whipping wind tore at the sheds and empty works and brave new shrubs on the way to the museum, which stretched, open and hope- ful, from Dudley down to the canal.

In the Victorian pub, a coal fire drew one into the snug. 'Pint of mild, meddum?' The landlord sounded oddly pious; his counter bore a scrubbed and sober mien. 'Beer all right, meddum?' He exuded certainty it must be all right, a local product. 'I was marketing manager,' he said casually, 'at Round Oak steel works, till their closure in 1982.' Awkward silence fell. What a nice Victorian pub, someone ventured. 'Would you guess,' beamed the landlord, 'it's an exact copy; they took down the pub at Buckpool and put it here brick by brick.'

No one could guess that the pub and the chapel and the chainmaker's house had all been reconstructed. 'I enjoy my job,' he drew another pint, 'never thought I would. Round Oak steel works employed 3,000 men.' He began to laugh. 'They're plan- ning shops I heard. Merry Hill shopping centre . . . we're resilient, oh we're resi- lient.' Crowds of school-children walked about the site, so clean and tidy in their brushed navy anoraks and neat ties. Where did they come from, asked a visitor.

'Wolverhampton,' a boy informed her col- dly, 'we're going to the Zoo next time.'

Mrs Gaynor Iddles in the chainmaker's house recalled how in the old days children took in in turn to go on the annual Methodist outing. One child per family. Mrs Gaynor Iadles, dressed snug and warm in black bombazine, showed off her iron kitchen range.

Everything glowed and purred. WoMen chainmakers user! to work 60 hours a week for a pittance. 'I never heard mum com- plain,' Mrs Iddles bustled about, 'now there's only part-time for women, you can't earn more than pin-money.' She wanted to chat but a party from Walsall filled the kitchen, overcome with delight: here was their own childhood, devoid of filth and misery.

Further down the canal, by the boat yard, a couple of men fixed rivets. One wrinkled little man said he wasn't a riveter, he was on the Community programme. 'It's grand,' he kept on repeating, 'it's grand. 1 wouldn't go back to industry if you paid me.' Get off,' laughed his mate, who had union jacks tattooed up to his armpit, 'there isn't no industry.' The Black Coun- try Museum employed 30 people under the Community Programme.

Both site attendants were redundant engineering draughtsmen. 'You've got to make the best of things,' one reckoned, pacing a slope humpy and pillaged by old mine workings. Lord Dudley once owned the colliery and the steel works. Lord Dudley had presumably done well out of them. 'We're left with the people, friendly, patient Black Country folk.' He sounded a touch unctuous.

We glanced at the Methodist chapel, brought brick by honest brick from Nether- ton, and went to the museum cafeteria for faggots and mash, rather good actually, served by a girl on the Community Prog- ramme. 'Not me,' she corrected, 'you got the wrong scheme, it's maybe Bert,' point- ing outside to a short man wheeling a barrow. 'It saved me,' he shouted over the gale, 'it saved me,' though unfortunately he lived at Wergs, which meant a bus-ride; so he would apply for a scheme at Wergs. There is a multiplicity of schemes and grants and projects, which people comapre as they would rival Methodist sects, re- deeming them from the outer darkness of unemployment. Some go for Primitive Methodism, others believe in direct aid from the almighty, since God helps those who help themselves.

Actuator Controls in West Bromwich seemed from the road a dull, insignificant place about the size of a garage. But they had received an innovation grant from the Department of Trade and Industry £100,000 — to help them put together hydraulic valves. Never having seen one, it surprised me to find a hydraulic valve in their workship towering huge and beautiful as steel sculpture in the Tate. A few silent men in boiler-suits were studying another valve, which had a cold, intricate beauty. 'Very sophisticated valve that.'

The manager introduced me to one of the fitters, who was being trained with help from yet another grant, given to meet the skill shortage. Frank Porter had an open, fresh face like a farmer, and used to repair lifting tackle. 'I prefer this job; it's got to be smack on.' He spoke soft and ambling, quite different from the West Bromwich splurt. 'I live at Wordsley,' Frank went on by way of explanation: a long drive to work. 'You have to,' he gave a helpless laugh, 'it's dead, industry, wicked. My friend a welder just been redundant for the fifth time. He hadn't saved nothing.' Frank sought for words and gave up. 'Such as meself, I was born to work; round here it's dead, it's wicked.' He looked at me, and the cold beautiful valve. We shook hands with Frank and drove away towards Dud- ley Zoo.

You can't visit the Black Country, they said, without visiting Dudley Zoo. It was right on top of a hill in Dudley Castle ruins. Sea-lions shrieked with boredom in the moat and a few parrots stayed out. A wild scudding sky kept most of the animals indoors. 'They're bored,' laughed Miss Skinner, curator of primates. A pair of white-handed gibbons, their little faces wizened and patient, sat grooming each other with delicate pointed fingers. In the next cage a grivet monkey from north-east Africa sat with head on hand, looking un- utterably sad. He had a white beard and amazing blue balls.

'When the sun comes out,' predicted Miss Skinner,' they'll cheer up.' But the freezing wind tore on. 'They need TV,' said a keeper,' they've got TV at the East Midlands Zoo.' By late afternoon, as the Queen Mary cafeteria was clearing away the ketchup, the wind dropped. A high Midland sky shed its light on Dudley. From the Ape House, you could see all the Black Country spread out in endless beige mud- dle. The monkeys were thudding and jumping about their enclosure.

Previous page

Previous page