Crime fiction (1)

New developments

Patrick Cosgrave

It is more than half a year since I have written a crime compendium in this paper. During that time I have been no less assiduous than before in the collection, classifying, reading and criticising of all forms of thrillers, detective stories, spy novels, et al, etc. But I have not written about them. ,First I blamed an unsympathetic literary editor. (Never having encouraged me before he now says he will allow me a compendium only every three weeks.) Second, I said I was too busy with other matters — an excuse which no serious crime etc., fan will allow. Third, I was preoccupied with a peculiarly difficult thriller of my own. Finally — and here, like any beaten man, I am on my knees, pleading that circumstances are against me — I argued that I had set myself too strenuous a task in trying both to give a theme to the compendium each time I wrote it, and trying to provide a survey of everything, both in hard and paper backs that was available. Only Mr Julian Symons, who is allowed generous space in the New Review and Mr H. R. F. Keating, who has devised a special review formula of his own which is allowed by the literary editor of The Times have managed to generalise and particularise at the same time.

Having got all that off my chest, I must confess to another problem, which is concerned with the nature of the crime etc., novel itself. All connoisseurs have admitted to a certain amount of worry about the direction of developments in the crime form. Mr Symons has, by and large, welcomed what might be called the sociological development, the drift away from heroes and adventure and towards the so-called straight novel. (It is true that his latest book, which I will mention in a moment, shows nothing of that — to me — intensely boring taste). That there has been some sort of collapse of faith in the more traditional forms — in the great detective, for example, or the well-nigh superhuman hero — there can be no doubt. This loss of faith has led to a number of interesting experiments, including the development of the historical detective story, most brilliantly last year in Gwendoline Butler's A Coffin for Pandora (Macmillan £1.95). The period setting, you see, frees imaginations restricted by the contemporary world. Excellent, however, though some of the historically based books are the growing number of them is worrying; for a form that ceases to find sustenance in its own author's time is starting to die. With that note of warning, however, I will turn to two historically based books that have given me enormous pleasure, Mr Symons's A three pipe Problem (Collins Crime Club £2.50) and Mr Robert Player's Let's talk of graves, worms and epitaphs (Gollancz £2.60), Mr Symons's book is historically based, however, in a contemporary sense: the action takes place today. But the detective is Sherlock Holmes! Rather, he is an actor named Sheridan Haynes who is playing the great detective in a long-running TV series, and occupies a flat in Baker St provided by the television company as part of their publicity drive. Haynes is, too, a Holmes connoisseur: he knows the books intimately, and he treasures the values they represent, as well as the skills of the great detective. In many passages of fine and ambiguous writing Mr Symons almost makes Haynes over into Holmes. Finally, jeered at by his colleagues, and mocked by his unfaithful wife, Haynes turns detective, and applies the methods of Holmes to the solution of a mysterious series of murders. There are

many fine things in the book — including meditations on the changed condition of London, which are especially beautifully done — but perhaps the finest is the way Mr Symons maintains the balance between Haynes's rather dotty ambition, which could so easily have toppled over into farce, the real seriousness of the crime, and the application of the actor's considerable intelligence to its solution. The book is a tour de force of a most uncommon kind; and the best thing Mr Symons has done.

Mr Player's extravaganza (as he describes it himself) is an equally stunning performance. It opens in the 'twenties, but is in fact concerned with events over the previous half-century. It is an account, by an ageing peer, of how his father, an Anglican Rector, married and with two children, as well as a mistress and a love child, became a Roman Catholic priest and, ultimately, Pope. The author is his son, put away from the father after the mysterious death of the mother, and the death of the mistress in prison, where she was awaiting the birth of a second love child, after being sentenced to death for the murder of her husband. The puzzle of the book revolves around the conviction of the narrator that his father killed his mother to clear his way for conversion to Rome and, ultimately, his rise to the Papacy.

All the characters, and especially the period, are brilliantly realised, and the tone of the writing which has just the right touch of engaging Victorian pomposity — is such that the reader is bewitched into accepting the extraordinary events of the tale as — well, not exactly normal, but perfectly plausible. There is a very strong detective element, for it is by no means certain who really killed the mistress's husband, nor that the narrator's case against his father, which he presents with overwhelming conviction and a mountain of evidence, is actually a valid one. The final conclusion — if conclusion it can be called — is reminiscent of the best of John Dickson Carr, though its preparation of a bewildering gallery of possible killers comes at the close of the book rather than the opening.

These two books, then, gave enormous pleasure, but they also started that nagging worry going again in the back of my head. They are both, as I say, tours de force, but neither can really be repeated. This may seem an ungracious point to make about two writers who are both so distinguished in the field of crime fiction, but it causes concern nonetheless. I am an unrepentant addict of series of books featuring the same hero; and there are very few crime writers nowadays — except, of course, writers for television — who, at a fairly early stage of their careers, have really strong heroes in contemporary situations, in book after book.

The problem of contemporaneity is nearly as important to me as the problem of the hero. Of course, the contemporaneity need not be real: Raymond Chandler's Bay City was a country in the mind; and no war hero in 1916 went through anything like the adventures in John Buchan's Greenmantle (to put together two very different kinds of book). But, about a contemporary fictional work there must be enough recognisable detail for it to feel real, and it is on this that the writer bases himself for the development of his fictional world. Perhaps the most compelling of such worlds is that of Chandler and Hammett and Ross Macdonald and the American private eye.

It is not a tradition that has ever been successfully transplanted to Britain. Of course there have been British amateur detectives galore, but the paid private detective is rare, and he is sometimes almost indistinguishable from the aristocratic amateur which British writers invented. Sax Rohmer had one (in Fire-Tongue) called Paul Harley; Peter Cheyney (both Mr Symons and the theatre critic of this paper, Mr Kenneth Hurren, jump down my throat when I confess a liking for Cheyney's Slim Callaghan) and there are a host of other examples. But the seedy conviction of the American, and the special argot which is such a vital part of the American tradition, have never been developed in Britain.

This is probably because the unromantic (actually, the private eye is very romantic, but he does not allow himself to appear so) vein in crime fiction has, in Britain, been developed among the offical police — in recent years especially on television. From Freeman Wills Croft onwards British coppers: have been the methodical, tough, hard grafting, heroes of the realist school of crime fiction.

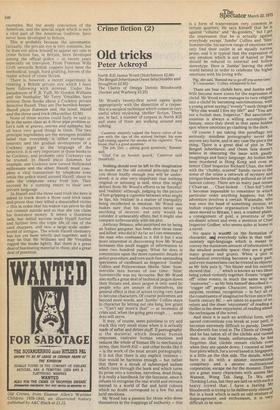

There is, however, a recent experiment in creating a British private eye which I have been following with interest. Under the pseudonym of P. ,B. Yuill, Mr Gordon Williams and the footballer, Mr Terry Venables, have written three books about a Cockney private detective Hazell. They are The born less keeper, Hazell plays Solomon and, the latest, Hazell and the three card trick (Macmillan £2.50).

None of these stories could fairly be said to be in the same class as A three pipe problem or Let's talk of graves, worms and epitaphs, but all have very good things in them. The two principle ingredients are the strongest possible belief that everybody is either corrupt or neurotic and the gradual development of a Cockney argot as the language of the detective. It is very important in these books to be Cockney, and probably only Cockneys can be trusted. In Hazen plays Solomon, for example, one Cockney now turned Hollywood millionaire and the other, Hazel!, must complete a vital transaction by telephone even while the police stand around Hazel!, about to take the telephone away from him. They succeed by a cunning resort to their own private language. In Hazell and the three card trick the hero is asked to track down a three card trick team and prove that they killed a dissatisfied victim — this in order that his widow can prove he did not commit suicide and so that she can claim his insurance money. It seems a thankless task, but initial success leads Hazell further and further into the triple life of one of the card sharpers, and into a large 'scale underworld of intrigue. The whole Hazell chemistry has not yet been wholly put together, and it may be that Mr Williams and Mr Venables regard the books lightly. But there is a great .deal of fascinating material in them, and a great deal of potential.

Previous page

Previous page