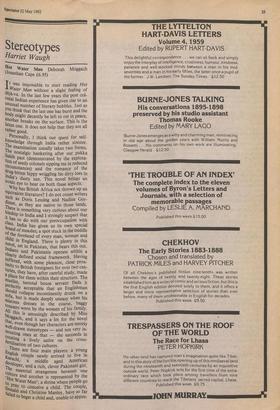

Stereotypes

Harriet Waugh

Hot Water Man Deborah Moggach (Jonathan Cape £6.95) it was impossible to start reading Hot -11-.Water Man without a slight feeling of deja-vu. In the last few years the post col- onial Indian experience has given rise to an unusual number of literary bubbles. Just as You think that the last one has burst and the body might decently be left to rot in peace, another breaks on the surface. This is the latest one. It does not help that they are all rather good. Personally, I think our quest for self- knowledge through India rather sinister. The examination usually takes two forms. The nostalgic hankering after our pukka Sahib past (demonstrated by the explora- tion of seedy colonels sipping tea in reduced circumstances) and the romance of the drug-bitten hippy wriggling his dirty toes in India's dusty sun. This novel brings an ironic eye to bear on both these aspects. Why has British Africa not thrown up an equivalent literature? I do not count writers such as Doris Lessing and Nadine Gor- dimer, as they are native to those lands. -9-lere is something very curious about our L inship to India and I strongly suspect that It has to do with our preoccupation with class. India has given us its own special brand

of measles; a spot stuck in the middle of the forehead of every man, woman and child M England. There is plenty in this I

11t)vel, set in Pakistan, that bears this out. ndians and Pakistanis operate within a Clearly defined social framework. Having s,uffered, with some pleasure, close prox- imity to British foreigners for over two cen- turies, they have, after careful study, made a Place for them within their structure. The Muslim, teetotal house servant finds it Perfectly acceptable that an Englishman should collapse incontinently drunk on a sofa, but is made deeply uneasy when his Mistress dresses in the coarse, baggy trousers worn by the women of his family. All this is amusingly described by Miss Moggach, and it says a lot for the novel that, even though her characters are merely well-drawn stereotypes — and not very in- teresting ones at that — she succeeds in creating a lively satire on the cross- fertilisation of two cultures.

There are four main players: a young

English couple newly arrived to live in Karachi, a middle aged American ueveloper and a rich, clever Pakistani girl. The essential strangeness between one Hot and another is represented by the to Water Man' ; a shrine where people go No Pray to conceive a child. The couple, nald and Christine Manley, have so far iad to beget a child and, unable to appor-

tion blame, find discontent spreading out thinly into every aspect of their lives. They have such diverging, cliche-ridden expecta- tions of Pakistan that you start reading the novel in the expectation of witnessing the collapse of a marriage.

Christine, pretty with frizzy hair, has an unspecific desire for independence. In Lon- don this had meant disliking domestic chores and having enjoyable, grizzly con- versations with like-minded, discontented radical women. In Karachi, however, she decides she wishes to experience the real Pakistan and immediately finds herself of- fending against the Pakistanis' sense of fitness. Christine has no time for the ex- patriot British community with its English food, beach parties, and women's get- togethers. She despises — as Western and touristy — the large bazaar where everybody does their shopping, and prefers wearing the loose baggy trousers of the natives instead of the neat cotton dresses favoured by the British residents. She is looked at askance by sophisticated Pakistanis when she squats at a party and eats with her hands. The servants are made uncomfortable by her wish to eat cheap local dishes, her usurpation of the gardener's duties, and her friendliness. Her attempt to find a job ends in very funny humiliation. She does none of these things with any sureness but out of a grumbling discontent. But she learns! 'Perhaps she should not tell him about the old clothes. He might not understand. He might hold her in lower esteem, and he was taking such trouble for her now. I am learning, she thought.' Christine is a latter-day Miss Quested and her troubled sexual response to the country is also suitably and convinc- ingly updated.

If Christine is familiarly tiresome, so, in a different way, is Donald. He is a weak man who looks to the solidity of the past to give him substance. Any woman married to him would be driven into the role of the modern woman in feminine fiction, even — as with Christine — a weakly, squeaky one. Brought up by ex-Indian Army grand- parents, Donald has come to Pakistan to recreate his grandfather's life in his own im- age. He fulfils the expectations of his houseman exactly, and wears Pakistan like a comfortably familiar coat.

The least successful character is the American developer. He is an over- simplified figure who believes he is impor- ting the American Dream when he builds his leisure complexes around the world. Seduced by the far more sophisticated Pakistani girl, run rings around by a cor- rupt bureaucracy, he becomes a broken man.

None of the characters are original crea- tions. They are there to represent certain common attitudes to India. This prevents the novel from rising much above the moral fable, which is a pity because the author has succeeded in giving the exact flavour of British ex-patriot life, its at- titudes, and the almost inevitably archaic role it is forced to play.

Previous page

Previous page